In the past year, it’s safe to say that many of our lives stagnated as the world found itself in an endless house arrest. Repeating days of online learning and choking-down ‘unprecedented times’ for breakfast, a glance to the future elicited nothing but an anxiety-laden fog and a queasy feeling. Many of us, turned inwards on ourselves, falling back into the soundtracks of 2012, revisiting our teen emo phase, and picking up old hobbies like skating. It appeared to be the standard way young people coped; when the present became too much to bear, we turned to our past. If you’re anything like myself, you may have also turned to TikTok, the Gen Z dominated app that seems to be everyone’s new vice.

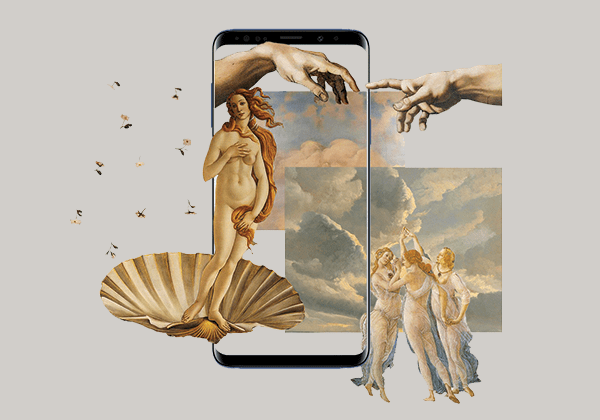

Over the summer, I couldn’t help but notice videos tagged #renaissance popping up all over my feed. At first, I was pretty pleased with the fruits of my labour (read: mindless scrolling) because I had finally reached Art History TikTok. Except, there was one small problem. Virtually none of the art used in the hashtag was actually from the Renaissance period. Most of it appeared to be Mannerism or Neo-Classical. The trained eye may immediately pick out the anachronisms of TikTok’s Renaissance, but it is easy to see how ordinary viewers may think otherwise. To defend Gen Z’s historical inaccuracy, Renaissance iconography re-appeared in varying forms long after the period officially ended. Though, how can it be that a trend with a cumulative 764 million views on the app is entirely historically inaccurate? This sticking point got me thinking about what Gen Z does associate with the Renaissance period; I concluded that the ideological connotations matter more than perfect historical accuracy. The trend reveals an entire generation’s relationship with the Renaissance, how we relate to it, and how we understand it as a cultural beacon.

It’s easy to suggest that the #Renaissance trend is appealing on social media for the romanticised opulence we associate with the period, but this still begs the question: why are these images still relevant at all? For me, the Renaissance is one of the most prominent symbols of cultural change in western history. Credited with bridging the gap between the modern-day and the Middle Ages, the Renaissance saw rapid innovations in scientific thought, culture, and politics, all of which paved the way for our modernity. The bold new imagery characteristic of the Renaissance bursts with themes of prosperity, individualism, and humanism. The fact that a TikTok trend has associated just the word ‘renaissance’ with its intellectual and lavish themes is indicative of the gravitas these artworks still hold today. I believe this is the crux of the trend’s motivation, and the reason for its comeback. In a year of pain, uncertainty, and loss, the Renaissance trend was a much-needed escape for an entire generation.

In itself, the gravitation of young people to the romanticised past trend is symptomatic of late-stage capitalism. The ways in which 2020 was ravaged by the knock-on effects of centuries of capitalistic greed were devastating and – even more devastatingly – predictable. Many young people became ‘essential workers’ or ‘frontline heroes’ – a thinly veiled way of sugarcoating the choice to work in a pandemic or not be able to pay rent. Further, the isolating format of online ‘learning’ only exacerbated students’ monotony and disillusionment everywhere. TikTok’s return to the Renaissance was a yearning for the past, a resounding outcry for escapism, with needs far surpassing lost high-school hobbies. To create or watch a TikTok that re-imagines the Renaissance is a therapeutic fantasy.

So sure, Gen Z got the art wrong, but they got the ideas right. Young people whose lives felt lost by the wayside in the stifling pressure cooker of 2020, turned to a time in history emblematic of creative expression and life’s beauty. Beyond this, it’s a yearning for a hopeful future, a possibility other than the nine-to-five and more years like 2020 to come.