Before the emergence of higher education in the West, older institutions were already teaching across the globe. Amongst them were the Confucian academies within the Sinosphere, which inherited the ideals of China’s Guozijian and were scattered across Vietnam, Japan and the two Koreas. These ancient temples of learning offer both an alternative to Western conceptions of scientific education, and a cautionary tale for meritocratic reforms elsewhere.

China’s Guozijian and the Imperial civil service exams

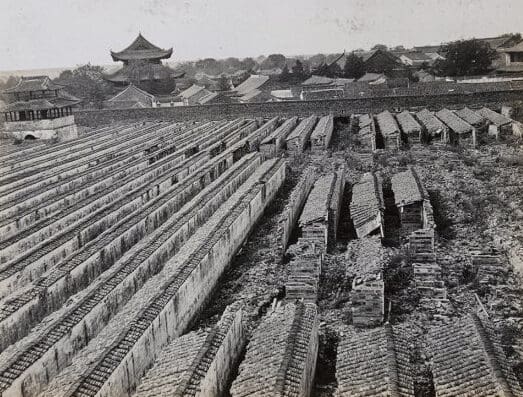

Founded in the 12th century during the Yuan Dynasty, the first Guozijian (北京國子監) in Beijing continues to stand amidst the hustle of city life. Unlike the Western conception of a self-contained campus university, China’s Guozijians were an apparatus of the state, serving as incubators for future bureaucrats who would serve generations of emperors and a literati class that would dominate cultural life.

In contrast to the liberal curriculum that emerged in Europe following the early modern period, the Guozijians revolved around recitation and meticulous textual and political analysis of the four Great Books of Confucianism: Analects, Doctrine of the Mean, Great Learning and Mencius, amongst a host of other works. These books, despite their emphasis on constructing a harmonious political system, occasionally provoked heated controversies. For example, The Ming Dynasty’s inaugural monarch attempted to prohibit all use of Mencius, deeming anyone who celebrated the philosopher guilty of lese-majeste (an offence against the state). This ended in a compromise, where ministers removed a passage that challenged absolute sovereignty of the government: “The people are the most important element; the spirits of the land and grain are the next; the sovereign is the least important.”

Within the Guozijians’ curriculum lies a notoriously demanding testing system — China’s imperial civil service exams. Men from any social class were eligible to sit in the lowest tier of exams in their respective province. If they succeeded, they were allowed to enter metropolitan rounds in Beijing and subsequently, the elusive imperial paper. The last of these exams were often supervised by the Emperor himself. This cultivated a literary elite that could administer local, prefectural and metropolitan governments.

Life as an aspiring scholar-official was arduous. Candidates contended with constant pressure from their family, and the high-stake exams exerted a price on students’ mental health. Indeed, an account by Shang Yanliu, the last tertius (third-ranking scholar) in a prestigious round held in 1904 Beijing, detailed the tolls the system exerted on students:

“In 1891 at the age of twenty, my brilliant cousin passed the provincial examination and became a provincial graduate. However, upon his return the following year to Guangzhou, from the metropolitan examination in Peking, he fell ill and died soon after. My mother said to me, “Too much intelligence shortens one’s life — better be a bit stupid like you.”

According to Benjamin Elman, the civil service examination system, despite its brutishness and gruelling nature, marked a radical change from purely political appointments towards a more meritocratic social order. But, despite its aims, this system entrenched class inequality as privately tutored students from wealthy landed gentries could prepare far more than the peasantry.

Following the collapse of the Qing Dynasty after the 1911 Revolution, the Guozijians were rendered obsolete. Today, the legacy of Beijing’s Guozijian lives on in the form of Peking University, an institution set up by Emperor Zaitian. Its premises include former imperial gardens and buildings of its predecessor.

Vietnam’s Quốc Tử Giám and the literati class

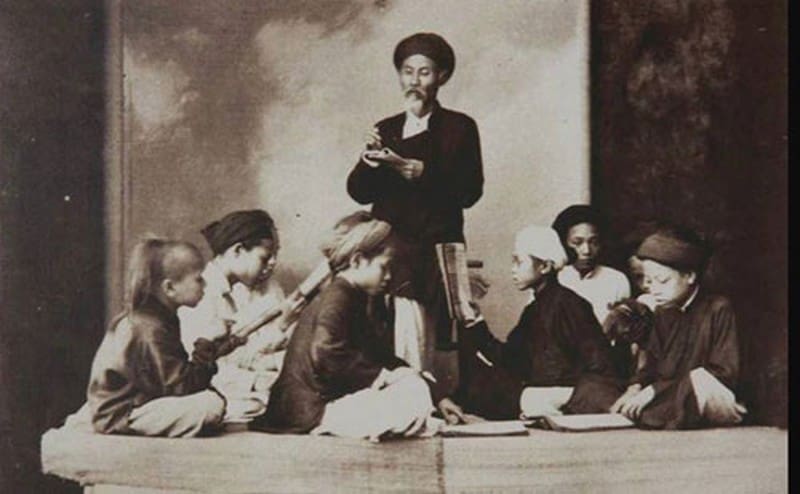

Established in a similar fashion to China’s Guozijians, Vietnam’s first Quốc Tử Giám — or the Temple of Literature — was founded in modern day Hanoi in 1076. The Temple did not commence formalised, regular instructions until 1272 following a royal petition for a substantial endowment. In keeping with its Chinese predecessor, Vietnam’s imperial academies taught the Great Books and Classics alike, and utilised a combination of Sino-Vietnamese and traditional Chinese (these institutions predated Alexandre de Rhodes’ reform of the Vietnamese language towards the Latin alphabet).

The grueling humanistic training that scholars received in Vietnam’s academies was not limited to rote recitation, but also the expert use of prose. One example is Mạc Đĩnh Chi, who became a national household name after securing the highest honours in his imperial exams at age 24. This was a rare achievement, given the vast majority of scholar-officials only passed provincial exams at a similar age and even then, these early rounds were intensely competitive. During a royal tour of Beijing at the behest of Külüg Khan of the Yuan Dynasty, the monarch challenged the scholar with a poetry challenge, writing:

‘Nhật hỏa vân yên, bạch đán thiêu tàn ngọc thỏ.’ or

‘The Sun lights aflame, the clouds above are smoke, by day they sear the Moon Rabbit asunder.’

In response to the Emperor’s boastful comparison of his kingdom to celestial objects, Mạc offered:

‘Nguyệt cung linh đạn, hoàng hôn xạ lạc kim ô.’ or

‘The moon is a bow, the stars are arrows, by twilight they pierce the Sun until her fall.’

In recognition of Mạc’s prodigy and sharp wit, it was said that Emperor Külüg Khan bestowed upon Mạc the title of lưỡng quốc trạng nguyên or bilateral zhangyuan, meaning the highest-ranking scholar across both kingdoms. As such, its civil service exam deployed prose and poetry to political effect, rather than as mere preparation for administrative duties.

Hanoi’s Quốc Tử Giám went on to teach until 1779, when Viceroy Trịnh Sâm closed the institution to prepare for the relocation of the Vietnamese capital to Hue. There, degree-granting powers were subsequently transferred to its counterpart in the Forbidden City. Over the intervening years, the Hanoi academy became a high school, and was later declared a monument historique under the French protectorate, thus becoming a museum. Following reforms introduced by French colonists towards a European university system, all academies ceased operations, despite partial efforts at restoration by the French School of the Far East.

The two Koreas’ Sungkyunkwan

North and South Korea’s institutions originated from the Gukjagam (국자감) in modern day Kaesong during the Goryeo dynasty, which was an integral parcel of Kaesong’s royal palace. This single institution would go on to experience several name changes, one of which was Sungkyunkwan (성균관) when a dedicated complex was constructed in Seoul in 1398.

Korea’s version of imperial civil service examinations was known as the gwaego. Since there was a very strict selection process, success in passing these tests entailed automatic employment in state administration. Each round of exams were separated by 3 years and limited to 25-30 examinees per session. The government also examined family history and ties of successful candidates — should students’ names or family ties indicate a less prestigious upbringing, they would likely fail even if they passed the exam. This represented a marked departure from the theoretically meritorious nature of neighbouring states’ approach. Hence, Sungkyunkwan acted both as a cultivator of the literati class and a protector of the feudal hierarchy.

Sungkyunkwan, however, did not wield a monopoly on Confucian education due to other institutions known as Seowons (서원). Unlike its sisters, Seowons were never founded under the direct auspice of any dynastic powers and were, instead, private neo-Confucian schools. The first Seowon — Sosu Seowon — opened in Yeongju in 1593. As per UNESCO’ heritage listing of Seowons, there are nine scattered across South Korea; the majority located next to rivers, mountains and other landscapes. Even though Seowons may have partaken in civil service exams, they tended to be local literati and intellectual hubs for the administration and enrichment of non-metropolitan cities.

Over the latter half of their existence, Seoul and Kaesong’s Sungkyunkwan witnessed mixed fortunes as Korea wrestled with political struggles against neighbouring Japan and then split when partition occurred. In 1592, for instance, Seoul’s Munmyo, a Confucian shrine at the heart of the campus, was destroyed during the Imjin War fought between Hideyoshi Toyotomi’s forces and King Seonjo. Subsequent years saw repeated revivals of Sungkyunkwan. Today, Seoul’s Sungkyunkwan has survived through its namesake 3-year university – Sungkyunkwan University – and its North Korean incarnation is preserved in Koryo Songgyungwan University alongside time-worn Confucian shrines at both schools. These institutions no longer offer regular instructions in the Chinese and Confucian classics.

Ashikaga’s Ashikaga Gakko and Tokyo’s Yushima Seido — Japan

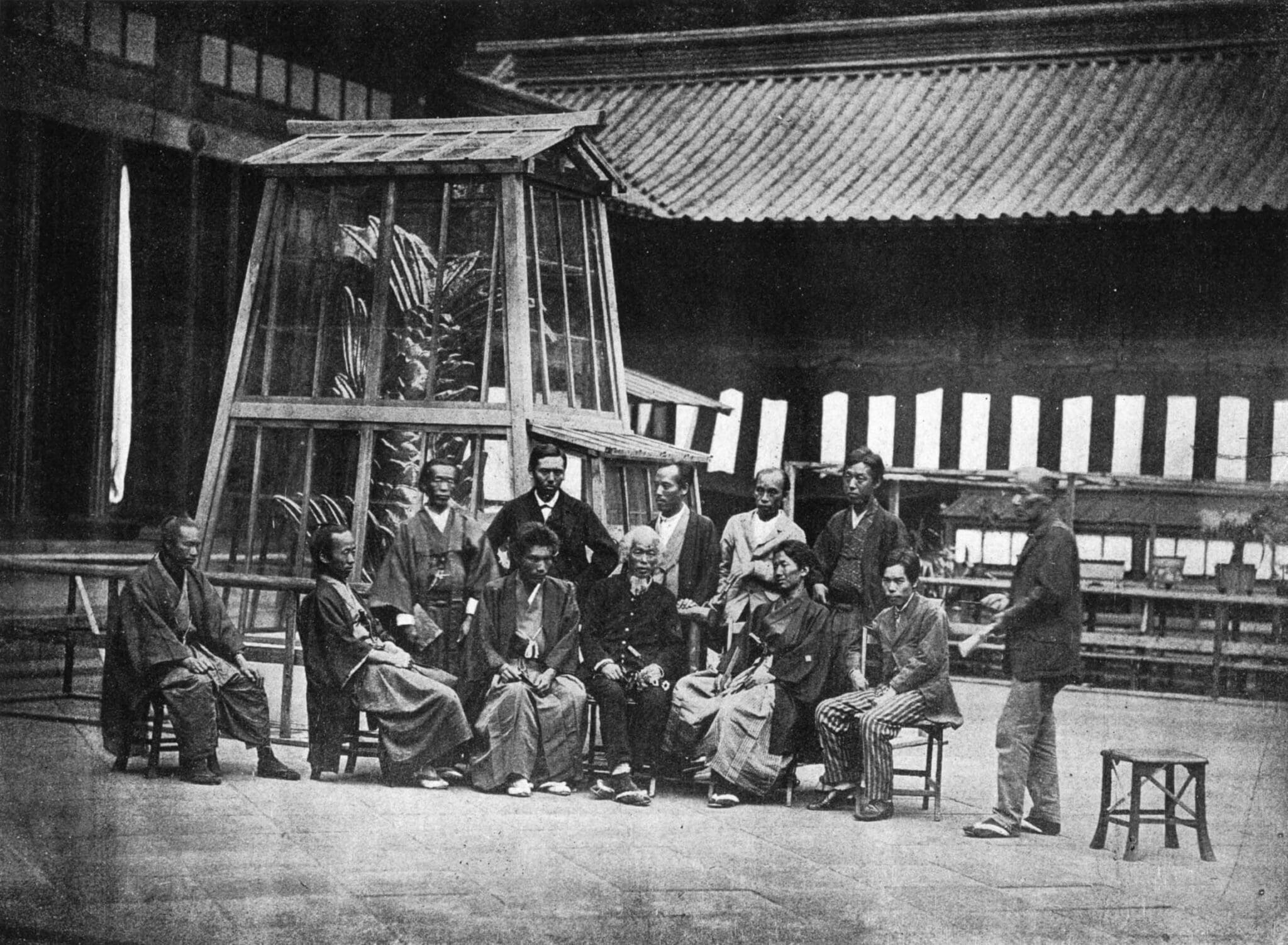

Unlike royal patronage offered to Chinese, Vietnamese and the Korean institutions, Japan’s Yushima Seido (湯島聖堂) was a private Confucian academy established by Hayashi Razan in 1630 in Ueno Park, Tokyo. Since the 19th century, the academy has been located in Yushima, within the precincts of Tokyo Medical and Dental University.

Although an earlier private academy, Ashikaga Gakko (足利学校) (circa 9th century, refounded 1432), predates Yushima, its relative isolation from Tokyo and the fall of its namesake Ashikaga clan resulted in terminal decline until it was converted into a primary school in 1868.

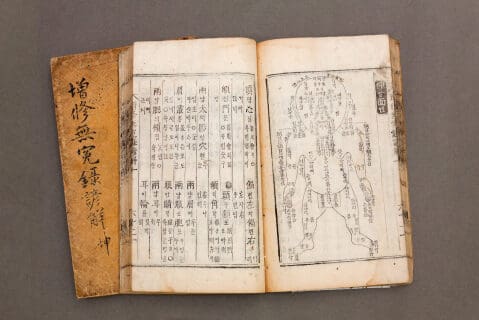

Unsurprisingly, the institution focused on studying the Chinese Great Books and Classics alongside Confucian ethics and philosophy. In contrast to continental East Asia, however, Confucian education in Japan wrestled with additional costs in the expense of imported classical Chinese texts from either China or Korea, which, according to Tsujimoto, were largely illegible to all but the founding Confucian scholars of Yushima Seido.

By 1797, Yushima came under the endorsement of the Tokugawa Shogunate. It transformed its role from a private Confucian Temple to a state institution that trained bureaucrats and diplomats for the Shogun. This change emerged following the issuance of the Kansei Edict by Tokugawa Ienari, which established neo-Confucianism as Japan’s official state ideology. Such a drastic measure, Peter Nosco argues, was triggered by social problems exacerbated by poor crops, famine and natural disasters. Another benefit of such a policy was to present Confucianism as an ideological bulwark against Christian evangelisation which accompanied Jesuit and Western missions to the country.

However, two key distinctions lie between Yushima and its East Asian counterparts: its leadership was hereditary rather than appointed through merits or a streamlined exam system. Thus, an unbroken chain of Hayashi descendants spanning over 200 years, starting with Razan and ending with Gakusai, governed the school until the emergence of the Japanese imperial university system. The other difference is that Yushima and the Shogunate never fully implemented China’s civil service exam system. Instead, depending on one’s social status, men could enter one or two out of four possible exams. Success would reward the successful candidate with a suitable court rank.

Yushima Seido, despite having lost its authority to teach Confucianism and Classical Chinese after Meiji Restoration reforms in 1870, continues to play a role in the cultural and educational elite of Tokyo. Today, it acts as a place where students can come to pray for luck and pay respect to an imposing statue of Confucius. Even if the classrooms of Yushima no longer witness throngs of scholars reciting the Analects or Mencius, its edifice is a constant reminder of Confucian influence.

***

The Sinosphere’s Confucian institutions are imperfect, with the majority of them adopting discriminatory policies against working-class students and a punitive examination system. This system survives today in the form of China’s notoriously difficult Gaokao (university entrance exam). However, they offer a glimpse into the political value of higher education from a non-Western context. This is especially important in the English-speaking world where tensions arise between the humanistic, socially-oriented inclinations of university education against the increasing corporatisation of higher education. Other jurisdictions, such as France, must heed the Guozijians’ cautionary tales of punitive exam systems, as the country’s tertiary sector is hindered by an elitist division between the grande ecoles and universities — the latter featuring first-year fail rates averaging 50%. Whilst the Sinosphere’s example exemplifies an outdated, feudal model of learning, it is clear that higher education is inherently political and indivisible from a state’s view of the human condition.