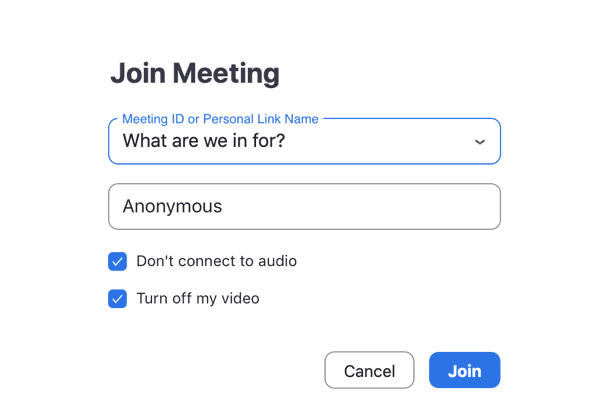

In a Zoom breakout room one day for a group presentation, I received a private message from one of my group members.

“What are we in for?”

Our presentation was in half an hour and she was trying to spell out a word for another member, whose first language wasn’t English. At first, it was easy to brush off the sentence as part of the gross blur that is online group work, but it left me unsettled.

***

Four years into university, I’m finally getting the hang of participating in class. Despite the downfalls of Zoom education, there have been a few perks that I hope I’m not the only one to admit. I have never been one to put my hand up and wing my way through class discussions. The thought of responding to a question is never a mere casual response, replaced by a fear of stumbling through a string of disconnected words. For me, “participation” requires curation; a careful draft of what exact words to say written into a notes app, or multiple attempts at drafting a message in the chat box, only to backspace it away. Though, slowly but surely, I’ve begun to press down the space-bar and unmute myself, even if just for a few seconds.

Another affordance of Zoom that I appreciate is the gallery layout. With the absence of body language, and hyper-awareness of how you’re sitting or fidgeting, Zoom equalises the student appearance. This may also, in some ways, link to the general air of informality of Zoom classes: roll out of bed and into your 9am lecture, though some people feel better having dressed — more power to you. Now, evenly spaced across a grid, every student occupies the same real estate and, at least on the surface level, has the same power to speak up and the relieving agency to be seen or not.

But the complexities of the digital realm make it harder to dissect. Social behaviours, microaggressions and unconscious biases have carried over from in-person teaching to digital spaces. There have been exhausting experiences in Zoom classrooms that required me to confront my own behaviours and what I was unconsciously communicating.

In the earlier Zoom interaction, I realised that I had somehow communicated a level of mutual ‘whiteness’ to her while casually exchanging pleasantries: “What’s up? How are you finding the subject?”, despite being an Indian migrant whose first language is also not English. Mutuality to a level where it had become comfortable enough for her to assume that we were feeling the same ‘frustration’ and ‘impatience’ with the need to mutually affirm a harmful stereotype of international students. Retrospectively, it’s difficult not to critique my own response to the situation. Why did confronting this person feel like a quick way to ruin the dynamic of a group that I’d have to work with for the coming weeks, even though the dynamic had already been skewed? Or perhaps wilful ignorance would have held a mirror up to her judgement. But at that moment, I choked.

Discussing this interaction with a friend of mine, we shared the ways we’d found ourselves compensating for our physical traits and body language on Zoom. For me, a thicker and more slurred Australian accent and, for her, a carefully curated backdrop that doesn’t look too brown, and a careful approach to pronouncing Vs and Ws. When pondering this, it’s easier to understand how it represents a subtle rejection and erasure of our upbringing and culture; a hyper-awareness ingrained in us in our endless attempts at an unattainable whiteness.

Despite experiences like this, there have been a handful of special moments that made me look forward to participating and engaging in class. Last semester, I had a class that was taught by a non-white tutor — one of only five subjects that I’ve taken in a total of twenty-eight. Fridays at 9am quickly became the best three hours of the week as our tutor checked in with students who were overseas, effectively popping the bubble of isolation; conversations ranged from chatting about favourite Malaysian food spots in Kuala Lumpur and Sydney, to the weather and skyline of different cities. The most safe and welcoming space at USyd wasn’t one that needed to manifest physically, but one that was created through conversation which welcomed the nuance of students’ backgrounds.

It’s not surprising that this experience is not the norm. While the transition to Zoom has been a solution for a relatively equalised learning space, the issues surrounding privilege and race have moved with it and largely remain unchallenged, overlooked and undiscussed.