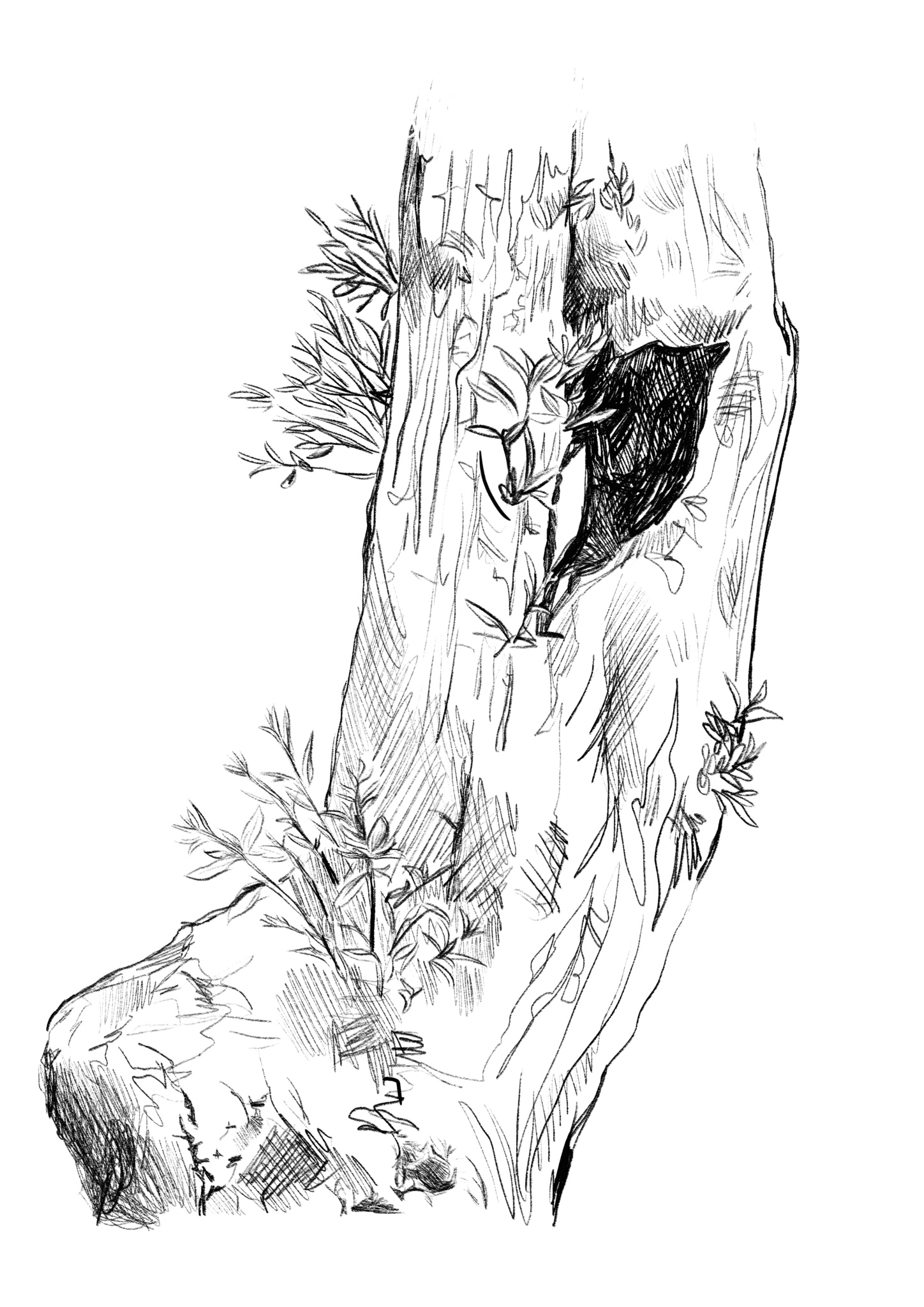

Evelyn Araluen’s inaugural poetry book Dropbear opens up the uncomfortable space between her personal understanding of the Australian landscape and the way it has been continuously redrawn and interpreted by colonisers. Araluen was born and raised on Darug land, and is a descendent of the Bundjalung nation. Dropbear is unapologetic and tough, dealing with issues of injustice such as Aboriginal deaths in custody and the ecological destruction of the climate crisis.

Araluen reveals anger towards institutions of power and oppression, but is also soft and vulnerable, making Dropbear an interesting and individually challenging read. In her interview, Araluen reflects on her ‘complex, tender’ feelings around anger, guilt and tenderness. Throughout Dropbear, Australian colonial history is probed, satirised and questioned, but never accepted.

The words of colonisers and today’s politicians are perverted and used ironically because Araluen tells me that she is “deliberately trying to be disrespectful” to them. For example she writes: “Don’t say Reconciliation Action Plan, say fuck the police” juxtaposing hollow parliamentary phrasing with a common Black Lives Matter chant.

Dropbear is a powerful, personal exploration of Australian memory and iconography. Araluen makes important statements about the hypocrisy of Australia from the First Fleet to disingenuous Acknowledgements of Country today. Her text reminds us of the forgotten: lost languages, the devastating bushfires a year ago and the power of connection.

***

Lia Perkins: The poems in Dropbear are experimental with form and style. How did you make these decisions and what was the writing process like?

Evelyn Araluen: I’m influenced by a lot of incredible contemporary Aboriginal women poets because that’s what my PHD was on. Writers like Ellen Van Neerven, Alison Whittaker, Janine Lane and Natalie Harkin. There’s very exciting formal innovation and experimentation going on in those spaces in Australian literature at the moment, and for my own process I spent a lot of time reading and researching contemporary and historical Australian literature. There’s a lot of my style which is simultaneously trying to honour and respect contemporary Aboriginal writers while also critiquing and writing back to the different styles of Australian settler colonial writing. I use satire and irony but balance it out with lyric and image as much as possible. Ultimately the book is about Australia, Country and the places that I love.

LP: How do you approach the tension between Australian classics about the landscape from your childhood memory and colonial and invasion history?

EA: It’s a really confusing mix of messages and representations that myself as an Aboriginal person, and my parents who made decisions about the kinds of stories to raise us on, had to navigate. I have patience and a respect for the way in which these kinds of stories try to engage with Aboriginal land and culture, but simultaneously I find that there are some really harmful, problematic histories to those methods. The whole thrust of this book was trying to find that in-between place of acknowledging what has created nostalgia and longing and these idealised visions of Australia. I’m hoping that the way that I have written the book doesn’t necessarily resolve the problems but it does clear some of the way and clarify that difficulty for future generations of Aboriginal writers.

LP: You explicitly reference the line ‘I can’t breathe’ from Black Lives Matter movements, and there is anger about invasion and colonisation. Do you see your poetry contributing to these ideas?

EA: I feel that poetry and all literature has a responsibility to call attention to injustice, but I wouldn’t say I think that a poem can in any way stop that kind of injustice. I think it’s really important that we think about it in terms of accountability and responsibility. We can ask, how has literature, storytelling and representation contributed to the issue without getting ahead of ourselves and thinking that we can somehow create some kind of perfect poem that’s going to end war, that’s going to end violence. I think my poetry can be a part of giving people better language to articulate injustice and the horrors of imperialism, settler colonialism or of other forms of social and political inequality.

LP: History very clearly ties in with those ideas that you’re talking about and in many ways you’re writing history, using historical sources and ideas. Would you talk about how you use poetry to do this and how you feel that’s done?

EA: The relationship between Australian history and Australian literary history is quite a lot closer than many people realise, especially when we think about how literary and poetic early writings about invasion and discovery and conquest actually were. My work is very informed of history, it doesn’t have much respect for the way in which settler colonial history is created and imposed over Aboriginal history and Aboriginal storytelling. So I’m deliberately trying to be disrespectful to those settler colonial stories and styles of storytelling.

LP: You’ve taught, researched and studied at Sydney Uni which is an institution with a deep dark, horrendous colonial history. Could reflect on doing your kind of research in the space of Sydney Uni?

EA: A lot of my rage and a lot of the anger in my book comes from institutions such as the University of Sydney and structures of power and imperialism. Institutions which exist to reaffirm the logic of empire, which is a logic of erasure and elimination. An education was incredibly important to me and something I never wanted to take lightly and disregard my own privilege in being able to access. However, throughout the years that I was studying at the University of Sydney I did encounter a lot of difficulty. It’s a deeply disturbing place and one that continues its crimes regarding the dispossession of Aboriginal land and the silencing of Aboriginal knowledges, and including now the exploitation of its workers and staff.

LP: What is the importance of the implicit and explicit references to climate change and environmental destruction in Dropbear?

EA: I think that talking about and organising around climate change is the most important thing for everyone and for every practice to take up. Poetry has a responsibility to talk about climate change because every art form, everything should be geared in that direction. I can’t narrate any aspect of my life, particularly not a life where I’m trying to talk actively about Country and culture, without acknowledging the impact of climatic destruction, ecological destruction on my land, my culture, my identity and the necessity of climate justice.

I hope that as anyone goes through their studies they take whatever opportunity they have to learn about the environment and the ways we need to protect it. Every word we write should in some way be conscious of that reality.