In the face of disaster, we have a tendency to shield ourselves from the bitter truth. But Danielle Celermajer’s Summertime: Reflections on a Vanishing Future expresses an emotional plea to bear witness to the climate catastrophe that continues to unfold before our eyes. Dany is a philosopher, and professor of sociology and social policy at the University of Sydney, who lives in a multispecies justice community in rural New South Wales. These influences meet in the sharing of her personal experiences during the Black Summer of 2019-2020 – stories of anguish and mourning that are not only deeply moving, but profoundly relevant.

I had the great pleasure of speaking with Dany about Summertime and writing about the climate catastrophe, ahead of her sold out appearance at the Sydney Writers’ Festival on the 30th of April.

***

Summertime is a book that was written with a very specific context in mind. The Black Summer Bushfires had devastated communities across New South Wales, leaving an incomprehensible amount of destruction in their wake. During this period, Dany wrote three of the pieces that would end up being included in Summertime. The first of these was written on the 31st of December, after Dany found out that Katy, one of the pigs that had been evacuated from her property, had died.

“I wrote that piece very much out of my anguish at confronting the vast chasm between those of us who were coming face to face with the fire, and what I call ‘the other Australia’ – an Australia that was still turning away – moving through life and the joys of summer as if everything was okay. That piece was really an appeal to try and close that chasm.”

In many ways, the closing of chasms can be seen as an ethos of the book in general, as Dany uses her own stories to bring the reality of the disaster to those that watched on from a distance. This becomes apparent in the second piece that Dany composed, with the subject of omnicide at its core.

“I wrote about omnicide when we started to find out the gargantuan number of beings who were killed, and the ecologies being destroyed. At the same time, we were facing a counter-rhetoric from the political right and the fossil fuel industry about arson and putative ‘green’ interference with preventative burning. It felt very important to me to provide a more accurate account of causality and responsibility. I wanted to talk about the ways in which those of us in the Global North are all, in very different and of course uneven ways, responsible for the mass killing.”

The third piece is a highly emotional story about grief. But at its core, is the experience of Jimmy, the surviving pig. This focus on the animal experience is what separates Summertime from the vast majority of other human-centric publications about the bushfires, and is a focus that is of vital importance to Dany.

“I approached it from that angle because that’s the orientation within which I both live my life and do my academic work. I convene a group called the Multispecies Justice Collective. Our objective is to shift the understandings of justice and ethics, as well as of the institutions that have been designed and developed to protect justice, so that they don’t just consider human beings, but also beings other than humans – animals and the environment.

At the same time, this is not only theoretical or professional for me. I live in a multi-species community. I have chosen to try to live in a way recognises the interests and flourishing of all other beings.”

But the justification for the non-human focus goes beyond the personal.

“I don’t think I was alone amongst Australians in being shocked… No. Shocked is such an understatement… Completely flummoxed by the breadth and depth of the killing of animals other than humans. Beyond the direct killing, these fires exacerbated existing patterns of habitat destruction and extinction, of which Australia already has a singularly appalling record.”

In her academic career, Dany has focussed on a variety of subjects, from transitional justice and Indigenous rights, to the wrongs of the past and the prevention of torture. Discussions of responsibility, complicity and involvement have run through all of these subjects. With this background in mind, I asked Dany about the issue of responsibility in public discussions about the climate crisis.

“I would not for a moment disagree that there are particular burdens that lie on particular individuals and institutions, such as executives in the fossil fuel industry, or the captains of right-wing media that undermine science and support climate denialism. Nevertheless, a fossil fuelled lifestyle is built into every aspect of Western modernity. It affects the way we eat, move, communicate, warm and cool ourselves, build our houses and cities. In that sense, we are all interpolated into systems that, as a matter of course, generate these outcomes that are dire for all of us. The impacts of these ways of living are highly unevenly distributed, both within humanity, and between humanity and non-human beings.”

Highly respected within her field, Dany has no shortage of acclaimed academic publications. Yet what became clear in our discussion, was that Summertime was intended for a different audience from her usual work.

“I wrote Summertime as a trade book rather than as an academic book because given the urgency of what I was speaking to, I felt that speaking to closed, academic audiences was no longer sufficient and that I had found a voice that was able to go beyond the circles within which I normally write.”

However, as an academic writer embracing the craft of storytelling, I was curious as to what Dany thought about the connection between storytelling, theory, and how ideas within these respective forms manifest in society. Does the storyteller have a unique role in shifting the discourse on important subjects?

“Storytelling, in the modality that we are accustomed to, tends to be about individual human protagonists doing things, making decisions, forming relationships, making mistakes, having personal transformations. Such stories are very good at creating affective responses in readers; in them we can feel for another character. In that sense, they’re particularly powerful. But the downside is that they’re not very good at narrating institutions and structures, so things like institutional violence, the way that structures of capitalism generate particular deleterious outcomes for forests or animals become more abstract, esoteric and less immediate.

I think the challenge for storytelling, a challenge that I tried to take up in Summertime, is how do we tell what I call ‘structural stories’? What I mean by that are stories that do the work of catalysing affect and empathy- allowing us to imaginatively live inside stories, but at the same time gesture towards the structures that actually animate the individuals within the story.”

Summertime is unavoidably a book about devastation. But at the same time, it is a book built on the foundations of a strong sense of community, and a firm presence of love. It asks us to confront the crisis that is the climate catastrophe, but reminds us that we are not alone in this fight.

“For many of us who already feel that they have a palpable relationship with what climate change might entail, I think there’s often a sense of fear in reading and talking about it. I really understand that. What I have tried to do in Summertime is not to shy away from the difficult truth, but to write it in a way that also illuminates the presence of the love that we feel when we realise what’s at stake.

It’s very difficult to stand in the truth by oneself. I know that. I feel that. But when we can create what we might call ‘communities of truth’, then maybe we are a little more able to do that together. There’s something quite intimate that happens between a writer and a reader, a special type of ‘we’ is created in that reading relationship. For people who feel afraid of reading about the reality of the fires, the reality of climate change, I hope that they could find in the book a place of company in all of those feelings, rather than being thrust into this very dark and frightening place by themselves.”

***

I spoke to Dany on the first dry day after over a week of heavy rain. The asphalt was still slightly damp. The grey of the sky, once heavy with rain, was only just turning blue. Eastern Avenue was littered by the mangled carcasses of umbrellas, abused by ferocious winds and heavy rain – the best that La Niña had to offer.

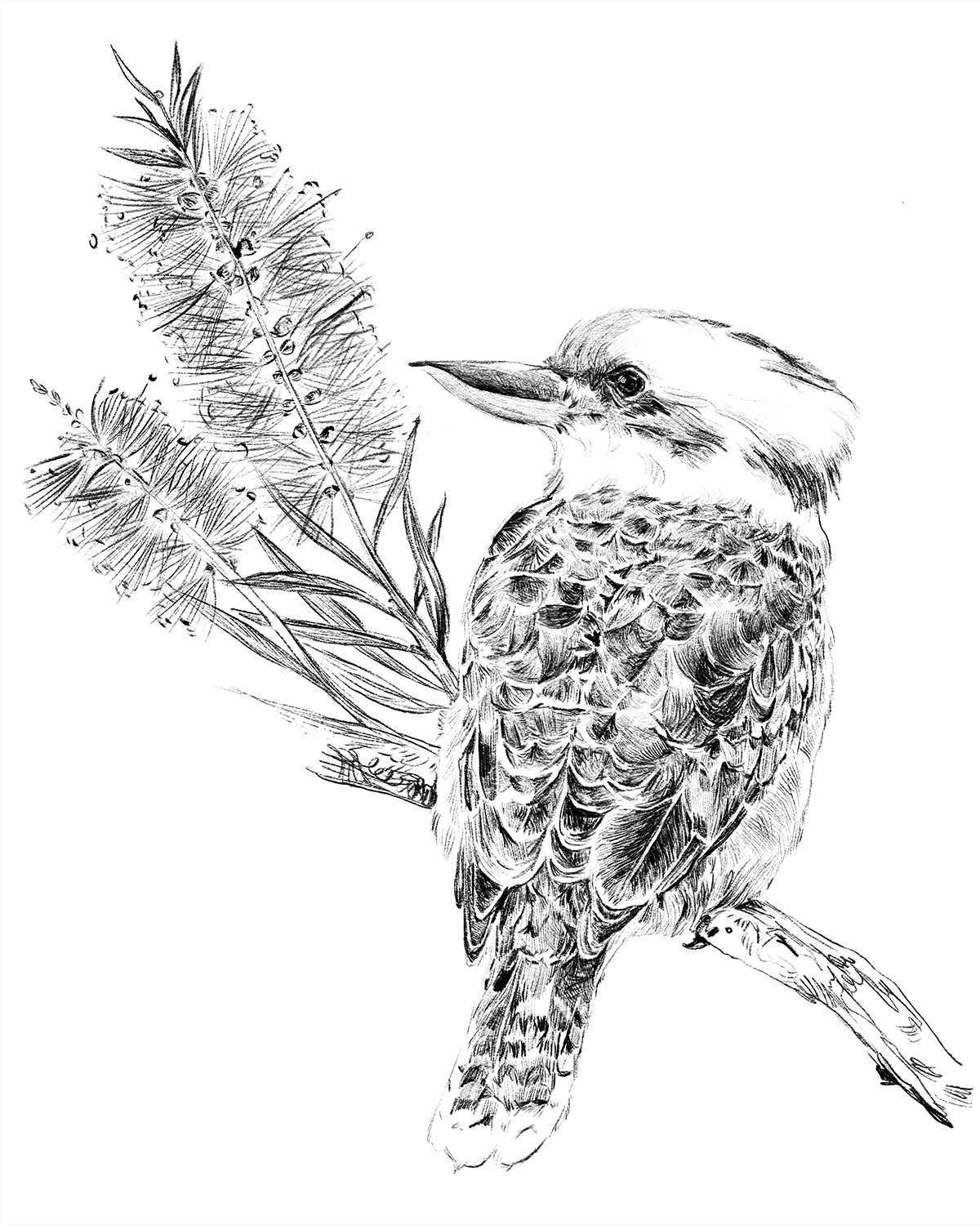

I looked down at the copy of Summertime in my hand, the cover emblazoned with Adam Stevenson’s photograph of a kookaburra staring out over a fire-ravaged landscape. I attempted to reconcile the image of the grey-blue sky with my memory of the murky brown that encased New South Wales only a year before. I tried to come to terms with a Janus-faced climate catastrophe – an insidious shape-shifter that appears in the rapacious rain, the ferocious fires, and in less noticeable forms in between.