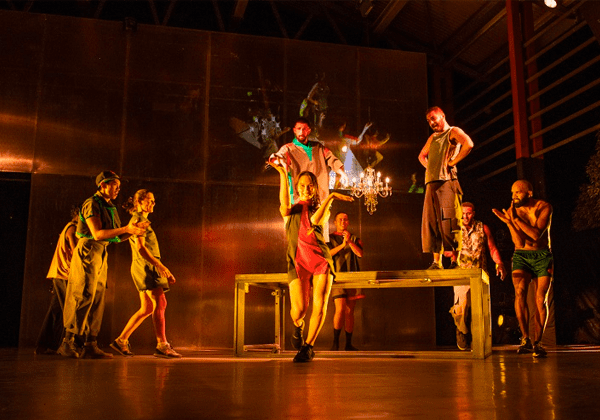

At an outdoor theatre in Broome, a dancer paces around a restraining chair in a lifelike prison cell. CCTV video projections paint the stage, evoking harrowing images of Don Dale Youth Detention Centre.

Jurrungu Ngan-ga — a Yawuru kinship concept meaning ‘Straight Talk’ — is a hybrid work of contemporary dance, spoken word and multimedia. Through its chilling performances, it defiantly confronts Australia’s crises of Indigenous incarceration and offshore detention.

“We wanted to create a conversation about Australia’s incredible capacity to lock up that which it fears,” says Director Rachael Swain.

Having completed a Master of Arts in 1999 at the University of Sydney, Rachael is one of many alumni of the Theatre and Performance Studies department, which is currently in danger of closure.

“Studying performance was an absolutely critical moment for me as an artist,” she says.

“I was exposed to a whole lot of writing which allowed me to connect our work to Indigenous scholarship, and to help understand my own position as a settler working in this space.”

Rachael took her newfound knowledge back to her dance company Marrugeku, which platforms Indigenous and intercultural performance and explores ways of decolonising contemporary art practices.

With Yawuru/Bardi woman Dalisa Pigram standing beside her at the helm, Jurrungu Ngan-ga is the latest of their many works.

“We had a lot of conversations about how we could embody cruelty on stage — not through a position of victimhood but through imagination and inquiry,” Rachael says.

“Rather than asking performers to ‘be afraid,’ they were asked to improvise ‘that which they are afraid of,’ allowing them to present their own explanations of fear.”

By being responsive to the dancers, audiences, and the political context of the performance, Rachael says their work challenges the “objectivity” of modern dance.

The dance company also embraces an experimental art-making process — one involving close collaboration with Indigenous people who have cultural authority over the content explored.

“Working closely with cultural custodians enables freedom in the exchange of knowledge systems and the meeting of traditional and contemporary understandings about performance,” Rachael says.

Some of the people the company has worked with include Elder and artist Thompson Yulidjirri, as well as Yawuru man and former Commissioner into Aboriginal Deaths in Custody Patrick Dodson.

“Audiences aren’t just seeing the end product — they are feeling the intercultural processes involved in the making of that work.”

For Rachael, it is precisely this social impact that necessitates the survival of the Theatre and Performance Studies department and the creative industries more broadly.

“Performance allows us to interrogate the world we live in,” she says. “Because of its ability to reach a wide range of audiences, it often moves faster than activism or political rationalising.”

“I really feel it can cross all sorts of boundaries politically, both within this country and around the world.”

Jurrungu Ngan-ga will be showing at Carriageworks in August. Check the website for more details.