If, as Joan Didion said, “we tell ourselves stories in order to live,” then we tell the stories of others in order to better know how to die. How to leave a legacy.

The biography is one such device. Last month, publisher W. W. Norton permanently halted distribution of Blake Bailey’s recent biography of American novelist Philip Roth after allegations surfaced that Bailey had groomed, harassed, and raped multiple women. It’s hard not to relate these revelations to one of the main criticisms from which his biography suffered – that he was uncritical of Roth’s misogyny, claims of which soured and followed Roth for much of his career. In fact, Ross Miller’s very frankness about Roth’s misogyny led Roth to end an agreement with Miller to initially write his biography. But any poetic justice in the mistreatment of women befalling the publication of Roth’s own biography is still deeply unsatisfying.

This is because it’s unclear what will happen to Roth’s legacy in the wake of this incident. Bailey was granted exclusive access to archives and materials about Roth’s life, which may be unavailable to future scholars in light of his passing in 2018. Perhaps there are pages still left unturned in his personal history, now mired in Bailey’s prose, between which more about Roth could be discovered. Despite everything, why does this feel like a loss? Why is it so unfair that even just a moment of insight could be snared by Bailey’s crimes? These events serve as context for larger questions about what it means to us as readers to preserve the legacy of great writers in a certain way.

Posthumous accounts of famous novelists in the Western tradition often serve to illustrate that great public works are made in spite of, or perhaps because of, private immorality. The collective history of many prolific white, male authors has invariably been one of mental anguish, narcissism, and chauvinism. When reading, it is important to historicise and put these men into context. But more than that, in the dialectic between author and reader that is shaping a legacy, we must learn how to reconcile the value of their literature, the truth of the person behind it, and the irredeemable fact of their death.

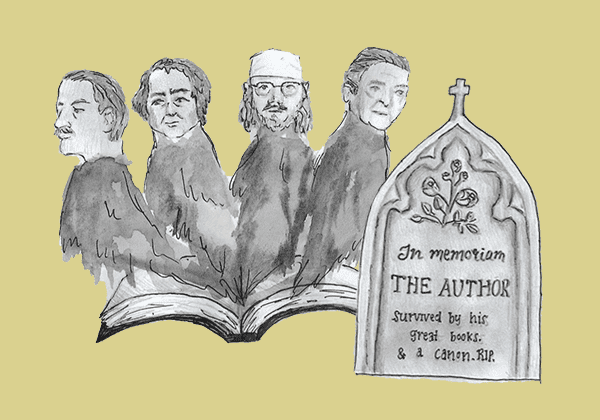

This need not be wholly a question of cancel culture, of separating the art from the artist; yet another way the storm of the individual washes away rivers of manifold experience. Roland Barthes most deftly maligned how literary critics inflect the meaning of a text with aspects of an author’s identity in his 1967 essay The Death of the Author. Barthes argued that readers must separate literary work from their creator in order to liberate that text from interpretative tyranny, where the experiences of the author serve as an explanation of some ultimate meaning of the work, handed down by the Author as God.

Underpinning the need to sever this relationship is the fascination we have with it in the first place. Quite apart from how many writers blur the relationship between themselves and their characters apparent in much fiction — particularly auto-fiction of writers like Proust — there is an anterior question, and we ask it not of the abstract, critical reader but of you and me: many men of dubious character, whose private lives were charged and broken and mythicized, create the conditions for questioning not just whether and how this influenced their work, but why it even matters to us if it did. At the heart of all this tension, in the tangle of our understanding, is that it seems to matter a very great deal to us who is behind the stories we tell, both irrespective of and because of what their stories might mean to us.

Consider how there is a scramble to publish a biography, make a tribute and publicise condolences after a famous person’s death. As soon as someone dies we have to ascribe meaning to it. Our fascination is not even entirely with the individual, but with mortality. Why do we need to understand someone to bury them? It is because they cannot be redeemed. It is because all we have is what we can become until we are no longer. Understanding the person who has died is thus an end in itself. It does not excuse them, but it helps us to forgive ourselves for seeing ourselves reflected on the page.

Although biographies are non-fiction, they invent. Lucasta Miller, the author of The Brontë Myth, is mistrustful of biographies in her own account of the Brontë sisters. She considers biographies a form of myth creation: what biographies invent they also reproduce for market consumption. This is another way that we reduce the reputation of particularly famous novelists into cultural objects which are sold as ideas or signifiers of genre or style or identity in a digestible form: read Jane Austen if you’re a woman into classics and romance, read James Baldwin or Toni Morrison if you want to learn about race in America, read Jack Kerouac if you’re cultivating your identity as a softboi. And while this is all true, in doing so we fail to appreciate what books do – how fiction transmutes ideas into people and how those people become us. We instead materialise and thereby minimise what they merely are as products of the people that wrote them. It works, too – personal branding infects a literary legacy. Just consider how unread copies of Infinite Jest tend to signal a kind of “literary chauvinism”; the ability to intellectually grasp male privilege, manifesting in performative displays of wokeness, because of how Wallace captures the disenfranchised white male in his work. It makes the rest of us deeply sceptical of these texts. To idealise, just like to hate, is to reduce someone to ideas about them. Fortunately for the writing itself, Didion suggests that “fiction is in most ways hostile to ideology.”

Ernest Hemingway’s life is a fitting example of the idealisation of our favourite authors — a man heralded as being at the forefront of war, surrounded by women and friends and bullfighting, whose sparse prose sparked a reckoning in American literature, pared back unto itself. The fact of his suicide is a lump in the throat when swallowing his personal history. Biographers continue to ask why, to decipher it as if it is some mystery, lest our ideal of Hemingway disintegrates. But it is no mystery – a familial and personal history of severe mental illness, alcoholism, and complex childhood trauma scream the answer. Some would say that knowledge of his suicide requires reading something new into his work: an identity crisis, an obsession with mortality, trails of wounded women, won wars and lost bullfights. The darkness of his life discovered after his death now casts shadows across his pages.

It may not even be controversial, merely disappointing, but it still shatters the illusion. To read Sofia Tolstoy’s journals and discover that her husband was cruel, critical, and inflicted much pain on her throughout the life she dedicated to him is to remind us that love, marriage and family may be no more than concepts in books. It is to render them unreal. In her words, “I devote so much love and care to him, and his heart is so icy.” To read T. S. Eliot’s love letters to Emily Hale during his first unhappy marriage, only to discover that he never married her after his first wife died and married Valerie instead. To think about how Hemingway dumped his first wife and child in Paris. Similarly, D. T. Max’s biography of David Foster-Wallace uncovers a portrait of a complex man “surprisingly disinterred in the real-life concerns of many women he slept with.” We ask, how can he write such exquisite prose and demonstrate such acute awareness of feeling and society, but be so inconsiderate of the people in his own life? Maybe sometimes people like the poetry of what they say more than they mean it or can ever put it into action.

To discover bad things, especially after death, simply hurts. The question, always the question, is why does it hurt so much?

The metaphorical death of the author is clearly made more difficult by their real-life passing. Jonathan Franzen provided his own account of David Foster-Wallace’s suicide in The New Yorker. He described the suicide as performed “in a way calculated to inflict maximum pain on those he loved most,” demonstrating “infantile rage” and “homicidal impulses.” He felt that Wallace “betray[ed] as hideously as possible those who loved him best.” The brutality of imbuing selfishness into a suicide seeks to undermine any martyrdom Wallace achieved in death. The searing need to be honest about someone who has died, the bleak portrait of being hurt by someone that you loved, captures a much deeper kind of betrayal. But rippling on the surface is the same kind of suffering we, as readers, face when we grapple with the reality of who a writer becomes after – and by virtue of – dying. The pain may come precisely from the fact that we do not know them personally and we can only know them as a representation or projection of themselves. The lines across the pages are like those on the back of our hand, but we still seem unable to grasp or reach anything with it.

In On Beauty, a novel itself about aesthetics and how the personal is always more real than the political, Zadie Smith remarks that “the greatest lie ever told about love is that it sets you free.” We are captured by the writers we love because they make real and legitimate what we are going through. To fall in love with a book is to be rewritten, in a slight and subtle way we may not even notice. There is no technology on Earth that can achieve what the novel can, no engineer like the author, no science like words. Because we emotionally invest in a writer’s work, our hearts get broken when we realise our captors have deceived us into thinking we were free to love them. Perhaps we can’t anymore, because the pedestal on which they sit has been lowered, and in our culture we find it impossible to love and pity simultaneously, to revere and condemn at the same time.

This is because we become complicit in elevating certain writers. We give cultural capital, money, time, respect, and literary status to those who have channelled the worst of themselves into fiction. In Franzen’s own words, Foster Wallace’s fiction “is populated with dissemblers and manipulators and emotional isolates.” Roth’s work was similarly rife with constant self-reference, sexual perversion, and vindicatory portrayals of raw masculinity. Compounding those feelings of complicity, we are often guilty of romanticising the relationship between the beauty of a text and the sordid reality of the person who wrote it – to make up for who the man was by what he created. Maybe he was just a bad guy. How can that change things?

George Orwell explores similar notions in his review of Salvador Dalí’s autobiography, Benefit of Clergy: Some Notes on Salvador Dalí. Dalí recounts incidents of severely harming children and women; his grave sexual perversity and necrophilia also manifest in his work. In spite of this, Orwell refuses to fail to see any merit in him. Against the facts of his life is the recognition that he had “very exceptional gifts,” was “a very hard worker” and “has fifty times more talent than most of the people who would denounce his morals.” Although Dalí was a visual artist, not a writer, the principle operates in the same way: “one ought to be able to hold in one’s head simultaneously the two facts that Dalí is a good draughtsman and a disgusting human being. The one does not invalidate or, in a sense, affect the other.”

But there is cognitive dissonance in holding these two thoughts in one’s head that is not one of logic, principles, or aesthetics. Indeed, as Orwell notes, “what is morally degraded can be aesthetically right.” It is emotional. It is a kind of love. Sometimes it hurts too much to accept that both those things are — that they must be — true. But novels should neither be reduced to the aspects which best reflect the person who wrote it, nor entirely removed from them. In Orwell’s words, “these two fallacies” presuppose a false binary: either a piece of art is intrinsically a reflection of the artist, or it bears no relation because its meaning belongs to its audience. The relationship between psychology and art is not so simple as to fall on either side of this dichotomy. People are not the sum of their parts. Authors give us the best and worst of themselves. They might be one terrible moment. They might be a thousand ambiguities.

Let’s not pretend that we can ever be objective or innocent about art. We taint a piece of writing as soon as we begin to read it because it is not the first story we have ever been told. As Barthes explained, a work is “eternally written here and now” because the “origin” of its essential meaning is exclusively in the language and its impressions on the reader. What applies to literary criticism also applies to our modes of appreciation — Milan Kundera speaks of “poetic memory,” the way we lodge into our minds and ascribe significance to that which we find beautiful and meaningful. It may be pretentious. It is certainly self-dramatising. But regardless of the significance you place on it, the process of reading, like remembering, like forgetting, is an act of interpretation.

According to German philosopher Immanuel Kant, aesthetics is a retreat from everyday life and its ethical questions. It requires a stance of disinterestedness, a space of moral freedom. Art is singular, without comparison and non-purposive. We must let art be possible. This does not mean it has to stay in print, that it should ever escape necessary criticism or that its sales can be abstracted from the finances of the person who created it. The artist is not exempt from what they are morally culpable for in their personal lives by virtue of their talent. If the facts demand it, by all means, be appalled! As per Orwell, “people are too frightened either of seeming to be shocked or of seeming not to be shocked, to be able to define the relationship between art and morals.” Define that relationship for yourself, as we all must define our own morals. Nothing is worth admiring unreservedly. But we must not take away its capacity for meaning. Letting yourself be upset may be precisely a part of that. After all, as Wallace said, “you get to decide what to worship.”

F. Scott Fitzgerald, as Nick Carraway, tells us that “reserving judgement is a matter of infinite hope.” Why then feel the need to eulogise a writer when their work lives on — to preserve what perseveres anyway, to make an ending out of theirs? When we do so, we attempt to pull together the strings of a person’s life into some coherent narrative — but it is fiction that there is such a thing. Lives do not end like plotlines. Resolution does not happen with time — sometimes it never does. People do not experience arcs like characters — they go through things. Sometimes they go forward, sometimes they regress and fall back upon themselves like waves. Adrift. Sometimes they don’t go anywhere at all, except inwards and onto the page. Could that be enough?

The most simple and morbid answer to why a legacy is important is that there is no answer. The answer is always oblivion. But as Sandra Newman said in her extraordinary novel The Heavens, as the character of Shakespeare, “I am a fool, and my greatness is the mumbling of fools; a paper greatness that will burn and be naught. But there is no greatness else.”

Let it be enough.