It took me starting university to learn that ‘Christian’ is a more fraught term with which to identify than my Catholic education would’ve had me believe. This is not because I associate religious beliefs with intellectual softness, nor because our secular University has forced me to take any measure of shame in the question of faith, but rather because people who identify as Christian often voice sentiments from which I would prefer, as a matter of basic decency, to distance myself. Best to lay these ambivalences down early, I figure: once I was Catholic, now I’m probably not, still I feel a measure of protectiveness over tenets of belief that are continually misappropriated by the very people who claim allegiance to them. But this article is not about faith, and it is also not about god. As at most times Christianity comes under scrutiny today, god rarely enters the frame. This is an apt point to begin with, and a crucial distinction to preserve.

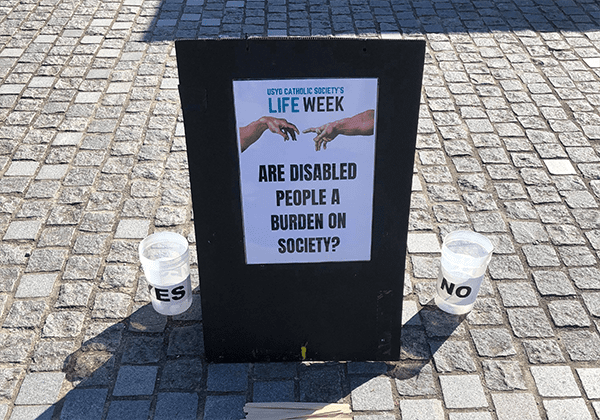

CathSoc’s A-frame on Eastern Avenue last week had an unmistakably Catholic flavour. After years in Sydney’s Catholic education system I recognised it immediately: the same discursive trick I saw performed in a hundred religion classes, the same I’m-just-here-for-open-discourse stance that allowed several teachers to declare anti-queer positions over the years while copping out of responsibility for what this really signified, which was that, in one way or another, some people’s right to live freely and securely was not all that valuable to them. Of course, CathSoc’s A-frame was in many ways a separate thing to this entirely; I don’t intend to conflate homophobia with ableism, nor suggest that posing a question is quite the same thing as expressing a view. But what felt familiar to me was the set-up of the act, its use of a rhetorical mechanism that is fast becoming a favourite of that subtler, more sensibly centred strain of religious conservatism which the Catholic church in Australia has come to embody so well.

What I am referring to is a kind of framing device, a method of staging a conversation that uses the banner of open debate to lend it a dignity that it doesn’t always deserve. Let me demonstrate this with reference to the classroom homosexuality debate, a spectacle marked in my memory for the way it began as a civil discourse which quickly gave staff and students occasion to share homophobic convictions as openly as if they were thoughtful intellectual points. While my Catholic-educated parents have confirmed that the pathologization of queerness is far from a new addition to the unofficial Catholic curriculum, they have also pointed out that its expression has changed: where once such prejudices were preached directly, today they take the passive but no less sinister form of a supposedly critical discussion. You have your view, says the speaker in this context, and I have mine; in this forum we are tolerant, dispassionate. The thing about discourse that is framed in this way is that anything is rendered passable: protected by the cloak of open conversation, one can question the utility of song in Christian prayer and the queer community’s right to basic dignities as if both were equally legitimate subjects of debate. But perhaps the most novel move of this technique is the way it protects its speaker from criticism, setting up the discourse so that those incensed by the question itself are easy to pin as threats to the cool civility of intelligent debate. Given that the people so incensed will frequently be queer, disabled or female – groups associated, in other words, with a hypersensitive imaginary left – the fruits of this rhetorical protection are often especially low-hanging.

Of course, CathSoc’s A-Frame had nothing to do with sexuality. I am not trying to impute a homophobic undertone where there obviously isn’t one, but rather to draw a line between what we saw last week and other kinds of harmful Christian rhetoric visible today. That CathSoc thought to ask whether people with disabilities are a burden, and that others sought to defend this choice (why are you apologising? reads one comment beneath their subsequent apology, don’t let outrage push you into an apology that isn’t due), reflects the danger of a discursive technique that uses the frames of free speech and critical conversation to legitimise questions which should not be asked in the first place. And this doesn’t mean that the question is aesthetically offensive, but rather that the very act of posing it, of putting out wooden sticks for passersby to cast a response, contributes to the ongoing exclusion of people with disabilities from a conversation in which their own bodies are the objects under debate. This is the biggest irony of the democratic language in which this discourse comes couched: more often than not, its structures reinscribe the otherness of a group it presupposes will not be present (are disabled people a burden? Should gay people marry?), thus refusing them entry to the conversation before it has even begun.

Judging from the kickback CathSoc has received, many people saw through a device that I am tired of seeing used to dignify the same monolithic discourse that has defined Christian conservatism for centuries. But others’ efforts to defend the A-Frame reflect the logic of a rhetorical technique whose invocation of a conservatism that is under assault by an overemotional, uncritical left is becoming all too familiar. As a secular citizen, I see the need for us to understand how this device operates so we are competent to name it when it occurs. And as an ambivalent Catholic, I long for a church that is honest with itself, that can admit when it is using the veil of free speech to evade accountability.