“If you would abolish avarice, you must abolish its mother, luxury.” — Cicero

Luxury, in the twenty-first century lexicon, has become an empty word — a shorthand means to elevate something with the promise of superiority and exclusivity. Luxury apartments (a mostly cookie-cutter, modernist high-rise hellscape). Luxury clothes (your designer logo anything doesn’t count). “Luxury” has become one of the biggest weapons in a brand’s arsenal when positioning their products, all in their relentless pursuit to sell a piece of that “dream” to the middle class.

The modern fashion industry has become a player in this game of deceit, although still retaining its last truest form of luxury — haute couture (French, of course, for “high dressmaking”). Historically, luxury fashion was for the rarefied milieu that could afford the pleasures of handmade clothes from the finest materials, meticulously made to the wearer’s exact measurements — for them and only them. The movement represented the highest example of craftsmanship and creativity, the source of all seasonal trends in fashion reflected in silhouettes, colours, tailoring, and textile choice — the zeitgeist. Suspects included the royal courts of Europe, American railroad tycoons and oil barons, and foreign dignitaries who could travel to Paris.

From its founding in 1858 by Englishman Charles Frederick Worth (known as “the father of haute couture”), to the mid-twentieth century where grand couturiers such as Gabrielle Chanel, Christian Dior, and Cristóbal Balenciaga rose to prominence, haute couture was an intimate affair. Clients were invited to the hushed salons of the couturier’s atelier, where they would be presented with the Spring collections in January, and Autumn collections in July, as models breezed down the halls holding number cards, indicating potential looks which clients could jot down and have made-to-order.

This hallowed ritual is in stark juxtaposition to how “haute couture” and luxury fashion is perceived today, all thanks to business-savvy luxury conglomerates. In the last 40 years, conglomerates snapped up luxury brands by the handful, buying out the descendants of their founders. The biggest players: Bernard Arnault, Chairman and CEO of Louis Vuitton Moët Hennessy (LVMH), and François-Henri Pinault, Chairman and CEO of Kering.

These luxury titans recognised the unprecedented buying power of the middle market, who were now showing a willingness to buy into the frivolities of luxury fashion. First came ready-to-wear (RTW), watered-down versions of the season’s couture in less laborious execution and less elaborate quality. Then came the streamlining of more accessible products such as perfumes, handbags, shoes, and accessories — all in the name of the democratisation of luxury.

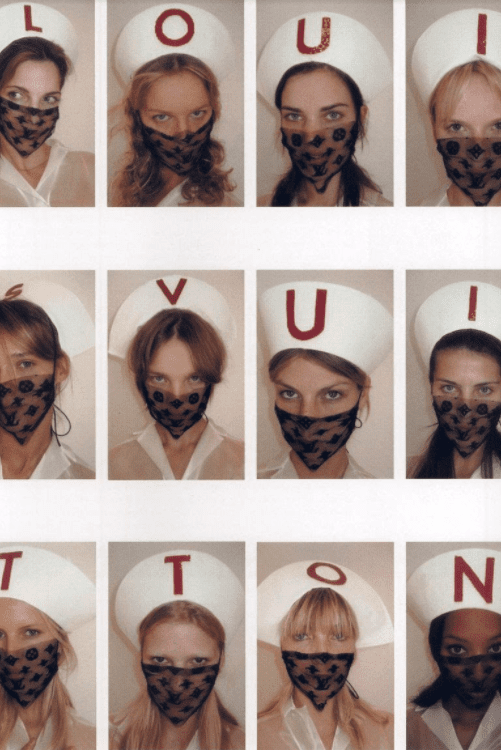

The greatest example of luxury pioneer to mass-producer is Louis Vuitton, which started as an artisanal luggage maker in 1854 by storing the fabulous clothes of the haute couture clientele. As every succeeding Vuitton generation passed, each added bags covered in the ubiquitous interlocking LV and Japanese flower monogram. After Arnault (nicknamed “the wolf in cashmere”) bought out Vuitton in 1989 (marrying the LV with the MH), he appointed designer Marc Jacobs as RTW creative director, leading to obscenely successful artist collaborations with Yayoi Kusama and Takashi Murakami. Today, Vuitton is the crown jewel in Arnault’s collection of seventy luxury brands and the world’s most valuable luxury brand, worth US$47.2 billion. During his tenure at Vuitton, Jacobs was quoted as saying “[if the clothes sell], if Mr. Arnault is happy, I’m happy.”

The democratisation of luxury, according to Anna Wintour, “means more people are going to get better fashion. And the more people who can have fashion, the better.” Perhaps Wintour’s words ring true, if she means an inclusive industry where anyone can associate oneself with a brand’s creative expression — sartorially tribal — but at what expense?

When a luxury conglomerate owns a fashion brand, much like all things they invest in, they expect immediate results. They appoint current and trendy ‘bad-boys’ of fashion as creative directors, and if their investment into the creative director doesn’t yield the expected ROI, they face the guillotine. Lifespans of creative directors, and creativity in essence, is short-lived under the guise of a corporate agenda. Worse still, creative directors are not kept long enough for their personal and the brand’s aesthetics to work in unison — forever a revolving door and an unsustainable flow of creativity, exposing both creative director and the brand to vicious reviews. Of course, there will always be fashion that is purely commercial, and luxury remains prohibitively expensive for a huge chunk of the population. But it is only when the creativity of directors comes up against the dictates of commerce that fashion as an art form becomes seen as less pure. leaving practices such as haute couture and artisanal craftsmanship to die off and become ignored. In an industry where the bottom line dominates, the way in which fashion has been supposedly “democratised” has cheapened craftsmanship. Slapping on a logo seems to be the go-to to make a quick dollar, calling brand integrity into question.

In addition, Arnault has made familiar a new luxury model: enhance timelessness, jazz up the design, and advertise like crazy. From a marketing point of view, luxury has become about selling a lifestyle, a heritage of craftsmanship. Conglomerates bolster the fact their products are made by artisans in Italy or France, as if making fine leather goods, beautiful fabrics and blinding embroideries are in their genes, continuing the legacy of fashion houses they bought out long ago. But while the “Made in France” or “Made in Italy” label is the cachet, the reality is that brands mass-produce these Eurocentric claims offshore to manufacturing capitals in developing nations, only to rip their “Made in China/Romania/Mauritius” label off and stitch on “Made in France”. Of course, most would never admit this.

The middle market has swallowed the concocted “dream of luxury”, particularly in China, India and Russia — places where luxury was abundant under the Tang dynasty, the Maharajas and the Czars. Now, illusions of grandeur in a culture of conspicuous consumption widen the wealth gap; covering oneself in European luxuries, synonymous with prestige, reinvigorates class hierarchies put in place by colonial histories.

In a fashion landscape where the supposed democratisation of luxury has cheapened it, and turned its perception into an empty word at the cost of creative integrity, what form does luxury take today?

The best practitioners of luxury in fashion today are with independent designers, where luxury is not only about the finest materials, but about an experience and a connection with their wearer — reminiscent of old-world haute couture. Here, independent designers can creatively operate without an underlying corporate agenda, concerning themselves with craftsmanship rather than the bottom line and doing away with the “out of sight, out of mind” manufacturing philosophy adopted and dominated by fashion companies. Here, wearers know the provenance of their clothes, and the importance of not compromising any aspect of their brand’s integrity — they are what keep fashion as a medium of art alive today.

‘Luxury’ has been hackneyed by marketing departments to give the middle class the impression of upward mobility, able to afford premium products. Meanwhile, in reality, the gap between rich and poor has widened tremendously, and the fortunes of conglomerates have grown. Luxury is haute couture and craftsmanship. Everything else is just very expensive.