Food insecurity remains a global problem leading to the impoverishment and malnourishment of underserved and disadvantaged communities. This is especially pertinent in the Global South where corporate food industries and neoliberal regimes continue to control land resources and food production, profiting from local agriculture. In Palestine, food injustice is the product of an ongoing relentless Israeli occupation on Palestinian life, land, and economy. Food sovereignty is proffered as a method of achieving food justice as a solution to rising poverty and food insecurity.

The beginnings of the food sovereignty movement were sparked by the struggles of peasant and Indigenous farmers in Central America. Carolyn Sachs describes the key components within food sovereignty as the “right to food, valuing farmers and farmworkers, local production and control, and environmental sustainability.” It is inextricably linked to many social justice struggles and is particularly tied to the feminist struggle. Women are disproportionately affected by food insecurity and face undernourishment, constrained access to land, and significantly less pay, despite producing the majority of the world’s food. This also frames the issue as one inherently of labour and the apparent gender divide present, however, it does not affect all women, nor does it impact women alone. Disparity trends in food access tend to be more prevalent in regions that have been devastated by colonialism and imperialism and their impacts on local food systems.

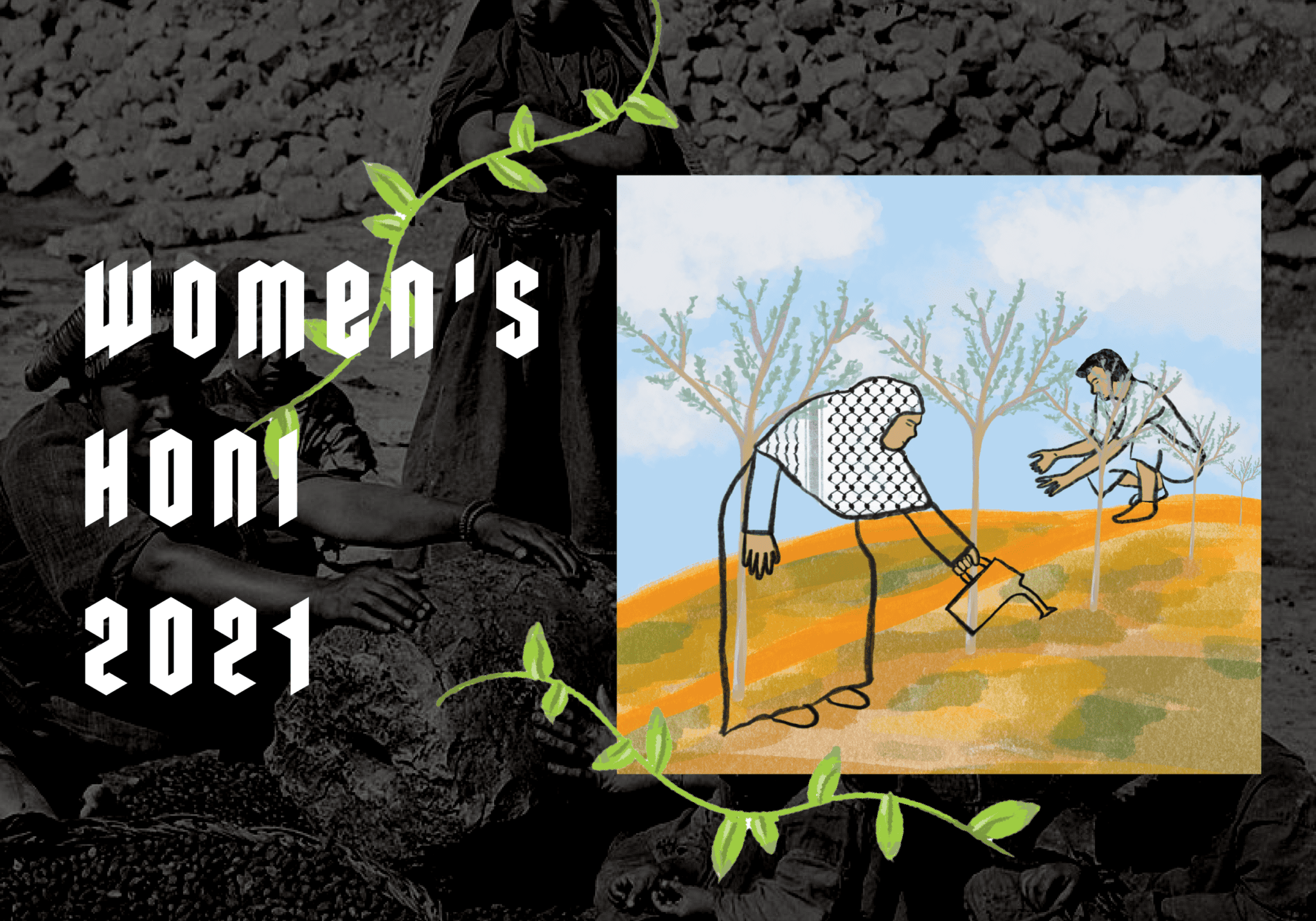

Israel’s ongoing military occupation over Palestinian land and life has deeply affected the state of food production, strangling the Palestinian economy in the process. Palestinians have been stripped of their own land for the benefit of Israeli use, leading to resource inaccessibility. For example, water shortages occur as a result of Israeli companies who control 85% of the West Bank’s water resources, diverting it from Palestinian towns to Israeli settlements. The lack of Palestinian self-determination, human rights violations, and theft of land and resources has resulted in inadequate infrastructure, water shortages, and other such limitations which have made food production difficult to sustain. Prior to the occupation, Palestine had a bustling food industry, producing an array of different crops and produce. Today, the olive industry forms the backbone of much of Palestine’s agricultural industry, which still faces obstacles due to the destruction of olive trees by settlers and lack of export markets. Olive trees serve as a significant cultural and political symbol for Palestinians, representing their roots and livelihoods. Additionally, they are a primary source of income for many families. The agricultural sector has also gradually deteriorated over the decades. It contributed 40% of Palestine’s economic GDP in 1970, and only contributes less than 3.5% today.

Food injustice in Palestine is an unmitigated humanitarian crisis. Palestinians face mass unemployment due to Israel’s restrictions on movement and the ongoing economic crisis which is a key contributor to the area’s high food insecurity. 37% of the population currently rely on food aid, and the incapacity to produce food has forced Palestinians to rely on Israeli produce and products. This only reinforces the political and economic cycle of dependence and further restricts self-determination. Earlier this year, at the beginning of June, Palestinians all over the country participated in ‘Palestinian Produce Week.’ The action aimed to protest the occupation and challenge Israel’s economic power and dominance over resources by boycotting Israeli products and supporting Palestinian businesses and Palestinian-grown produce.

Building food sovereignty in Palestine is being attempted through several means, mainly through localisation. Local food production, as a way of keeping Palestinian food traditions alive and as a form of resistance to the occupation, has been termed ‘agro-resistance’. In the town of Beit Sahour in Bethlehem, a seed library has been created as a way of preserving local fruits and vegetables, and of providing farmers with the opportunity to borrow and share seeds. Methods to alleviate the impacts of increased urbanisation and land loss have also been developed, such as assisting Palestinians in Gaza to capture rooftop rainwater to counteract shortages and to water gardens. The Ma’an Permaculture Centre trains and educates farmers, providing them with initiatives to grow food for local populations and opportunities to learn innovative farming techniques.

Food sovereignty is inherently interrelated with Indigenous sovereignty. In Australia, Indigenous land rights are in conflict with hyper-capitalist modes of food production and Australia’s agricultural industry more broadly. Like Palestine, food injustice in Australia cannot be disconnected from a broader global context of colonialism. Indigenous food sovereignty facilitates ‘collective continuance’, which Kyle Whyte describes as “an ecology of humans, non-humans, entities, and landscapes that enable ‘adaptation to change.’” Achieving Indigenous food sovereignty requires decolonisation, resisting capitalism and the revival of Indigenous ways of life.

Impending climate catastrophe and its ability to threaten food production further leads us to search for new modes of sustainable agriculture. To achieve food justice, it is imperative that farmers, peasants, and small producers control food production, including distribution. Food sovereignty, particularly amongst Indigenous people living in colonised nations, achieves fair food practices that are in line with the needs and cultures of specific populations. Food sovereignty additionally provides adequate supplies of high quality food and greater food independence, preventing malnourishment. Food sovereignty also allows marginalised populations, especially in the Global South, to maintain culturally-specific forms of food provision, preparation and sustenance.

Food sovereignty has evidently been disrupted by unfettered capitalism, colonialism and the wholesale destruction of traditional ways of life. Tackling food injustice should be at the forefront of all social justice movements as it is inherently inseparable from social justice struggles such as economic, gender, and racial inequality. Achieving food justice is, therefore, essential to achieving justice and equality for marginalised groups.