When I think of Western Sydney in the throes of summer, I think of burning concrete plains in near unlivable suburbia. When I was in high school, my guinea pig died of heatstroke on a 46°C summer day. I had been at the beach when it happened, and I hadn’t realised how hot the day had been until I stepped off the train at Wentworthville Station. Trudging home through the soupy air, as the burning pavement pierced the soles of my shoes, I could sense that something was wrong. I quickened my pace, and while turning onto my street, nearly stepped on a dead myna bird that lay on the curb.

There are precious few grown trees in my neighbourhood that offer shade on hot summer days, and on the hottest days, suffocating heat waves quiver above the grey bitumen. Perhaps if there were more trees to offer shelter and reprieve, life would be a bit more bearable. I live on Darug land and before colonisation, the local area would have been blanketed in native grasses weaving between sparse groups of trees, with fire stick farming — the practice of setting controlled fires — used extensively in the area by the Darug people to maintain the land. But anything magnificent and unruly that once grew here has long been uprooted to make room for broad concrete roads, powerlines and barren lawns of monoculture grass.

One need look no further than Western Sydney to see that the climate crisis is already here. Hot summers draw large crowds to air-conditioned shopping centres, as many residents are unable to afford air-conditioning in their homes. At present, Western Sydney is already palpably warmer than Eastern Sydney suburbs on an average day.

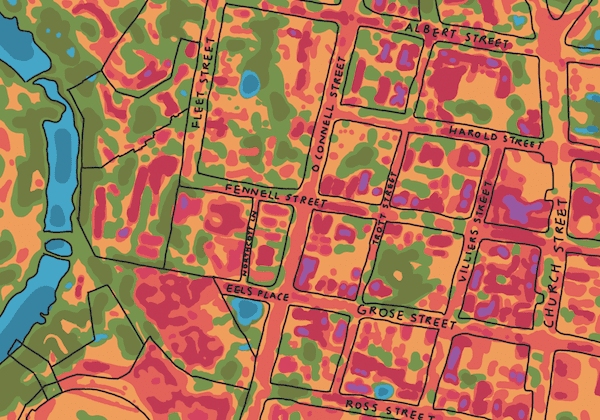

The unbearable heat of Western Sydney in summer can be chalked down to many factors. Most notably, the inland position and built environment of Western Sydney sets the area at a marked disadvantage, in contrast to the sea breezes that grace the Eastern suburbs. The relief granted by the sea breeze ends somewhere around Homebush, according to Dr Sebastian Pfautsch, a researcher and expert on urban heat from the University of Western Sydney. The heat gets worse the further out west you go; suburbs within the affected triangle of Blacktown, Windsor, and Penrith are the hottest parts of Sydney, forming an urban heat island. Western Sydney is uniquely prone to the urban heat island effect due to the built environment of roads, footpaths, and roofs. With vast heat-absorbing concrete plains exposed to the sun during the day, there is nowhere for the trapped heat to dissipate except in the areas around it.

Additionally, green space in Western Sydney is ever-vanishing. One of the most common requests made to local councils is to cut down large trees, and development begets disappearing bushland. The lack of green spaces in Western Sydney, coupled with expanses of heat-trapping pavement, makes heat difficult to manage in summers. Dr Pfautsch identifies a mass conversion from “green infrastructure to grey infrastructure, from pastures and meadows in agricultural land into shopping centres, car parks and residential suburbs.” More areas dedicated to natural greenery would allow for more effective cooling because green areas allow for water to penetrate the ground in a way that concrete doesn’t. While more affluent suburbs are afforded these spaces, Western Sydney has limited access to such luxury.

As Western Sydney is on track to become another CBD with the development of the new airport in Badgerys Creek and new neighbourhoods like Marsden Park, I find it hard to believe that city planning is prioritising the preservation of green spaces. There are no significant green spaces within walking distance of where I live, in the local government area of Cumberland; only footpaths, highways, and concrete; evermore concrete. Classism is transparent in the way that cities are built, and the lack of green spaces in Western Sydney communities is only one such example. Everything about the way that Western Sydney is treated in times of crisis reveals the priorities of elected officials; the extreme policing of Western Sydney communities during lockdown this year reflects an apathy by the government that is all too plain in their weak climate policies. While we are expected to vote and ask nicely for climate justice, the earth is dying.

Today, if you drive along Richmond Road, past a great concrete shopping complex that houses a Costco and IKEA, the sporadic patches of bushland fall away to reveal monotonous rows of identical houses, with not a tree in sight on nature strips. As the remaining reserves of bushland in Western Sydney are razed to make way for development, the imbalance of green and grey grows.

Current research into the future of Western Sydney’s summers paints a grim picture. According to the Australia Institute, the number of days over 35°C per year in Western Sydney have almost doubled since the 1970s. Data also predicts that by 2090, the average number of days over 35°C in Western Sydney could increase to 52 days a year. Meanwhile, the radiating heat of pavement can reach 80°C, while the surface temperature of playground equipment can reach 100°C.

Further out west, in areas like Penrith and Richmond that sit at the foot of the Blue Mountains, the situation is even more dire. On 4 January 2020, as bushfires raged through New South Wales, Penrith became the hottest place on Earth, with temperatures reaching 48.9°C; nearly halfway to the boiling point of water.

Long term heat exposure has a range of detrimental effects on health, and may cause long-term heart, kidney, and liver damage, or infertility. Humans are not built to withstand temperatures above 35°C for extensive periods of time; at this point, the body’s ability to cool down is compromised. Heatwaves kill more Australians than any other natural disaster. It is physically dangerous for people to be living and working in temperatures above 35°C, but this reality is already lived by many out in the West.

We have a decade to prevent our planet from descending into an unlivable hell, but the fact that Penrith, where my little brother goes to high school, was (even momentarily) the hottest place on Earth is a reminder that the climate crisis has already begun to work irrevocable damage, and will continue to scar us for decades to come.

Across greater Western Sydney, we are already seeing band-aid solutions being implemented to mitigate, even if temporarily, rising heat. Blacktown City Council has introduced a heat refuge network, with community air-conditioned spaces for those who are most vulnerable in events of extreme heat. The Western Sydney Regional Organisation of Councils (or WSROC) has prioritised tackling the urban heat problem through their Turn Down the Heat Strategy and Action Plan, which has seen efforts of urban foresting in Penrith and Blacktown local government areas.

But young trees do not have the same protective effect as fully-grown trees. Unfortunately, it’ll take around 20 years for WSROC’s planted trees to grow enough to have a significant effect, and by then it’ll be too late. In fact, all of these strategies to cool Western Sydney feel too little, too late.

The thing is, try as we all might, the climate catastrophe is upon us and there are larger factors at play that will determine the course of the planet.

In July, Canada saw heatwaves that killed hundreds of people, many without air-conditioning in their homes as a result of Canada’s naturally cooler climate. Temperatures soared to past 45°C, previously unheard of in Canada.

As August ticked around this year, scientists spotted warning signs of a potential collapse of the Gulf Stream, which would be a critical tipping point in the climate catastrophe. Yet, with less than a decade to heal our ravaged planet, global leaders are still happy to let poor people and people of colour die. Planting a few trees will do precious little to offset the damage of state and federal governments that continue to bolster and fund mining conglomerates and the fossil fuel industry. Planting a few trees will not help the land forget the terraformation begun by European colonisers, who brought invasive flora and fauna that ripped through the delicate balance of ecosystems across the continent.

It would be remiss to lament the debilitating heat of Western Sydney summers without attributing the searing heat to the colonisation of the landscape. Signs of colonial terraforming can be seen everywhere, if you care to look. Consider the mundanity of the monoculture lawn, imported by colonisers as a symbol of wealth and superiority, carving out pockets of curated nature that are ill-fitting of native ecosystems. Consider the lonely ibis that digs through bins, dispossessed of its natural wetlands.

Colonial ignorance and hubris are to blame for the climate crisis that we are faced with today; colonisers who thought they knew best when they brought invasive flora and fauna and sought to wipe out complex systems of knowledge and agricultural wisdom that had seen the land thrive for millennia under the custodianship of Aboriginal peoples. Two centuries after invasion, decolonisation is our only hope. First Nations leadership is critical if we are to have any hope of saving our planet.

Even today, I cannot find the words to express how terrified I am of what another decade of catastrophic climate policy could mean for Western Sydney. The sheer scale of the urban heat threat is unlike anything we have ever seen before. Despite the growing problem of urban heat management, a symptom of government negligence and global inaction against the climate crisis, the NSW State Government is aiming to move another million residents to Western Sydney in the next 20 years. But what kind of future will be lying in wait?

Western Sydney is my home. It is the beating heart of two and a half million working-class people, immigrants and First Nations people, and we will not let it go gently into the night.