If you’ve ever caught a train, driven down Parramatta Road, or walked through any main streets of the Inner West, chances are you’ve seen graffitied ants or the word “flora” scattered about. The tags range from illustrations of ants and flowers, to various iterations of “8it”, “pest”, or “flora”, which seems to be the main tag. They have a visually distinctive style characterised by bold outlines, blocks of colour and imperfect shapes — indicating that they’re all the work of one local artist, or perhaps a graffiti collective. We decided to investigate the infestation of ants that appear to be slowly spreading through Sydney.

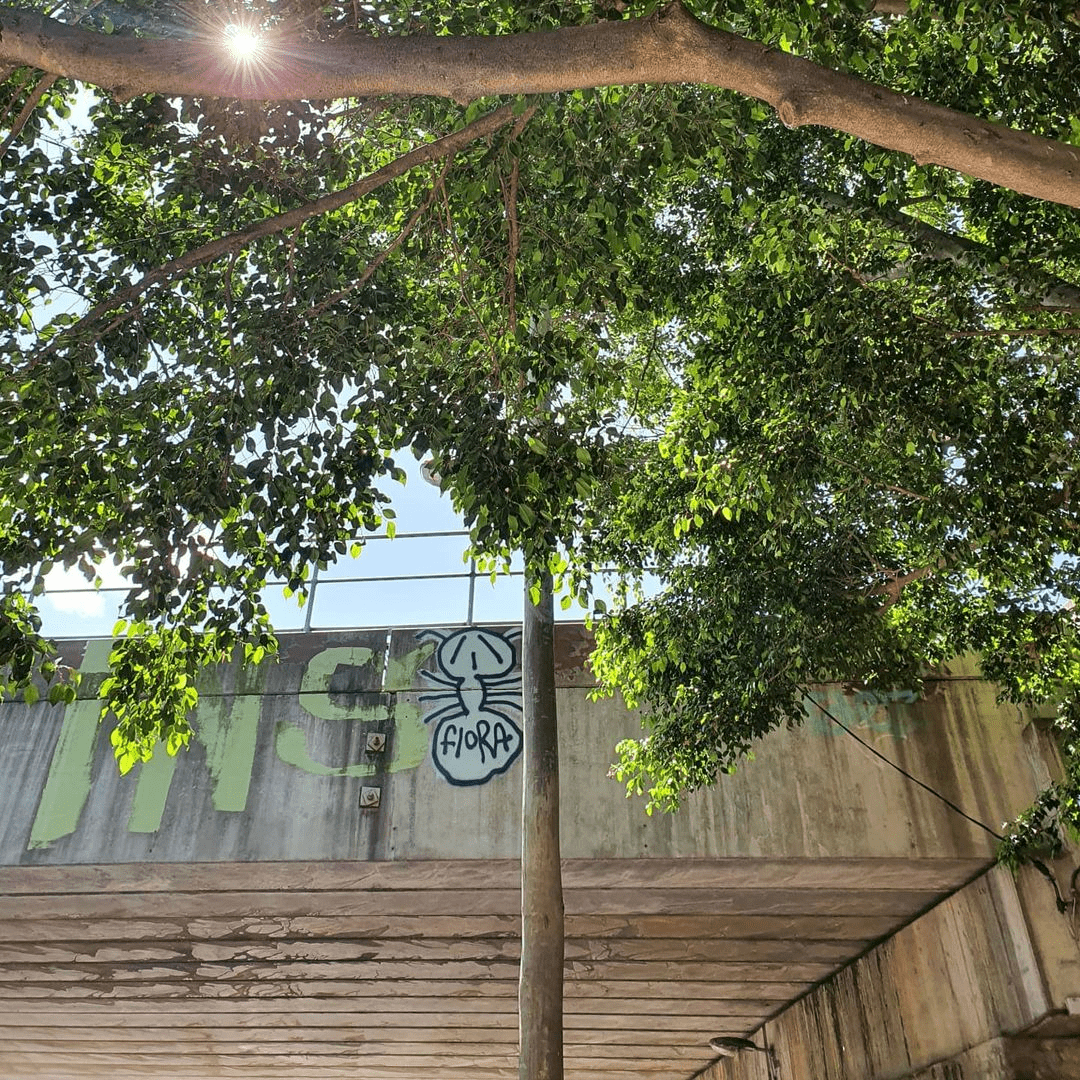

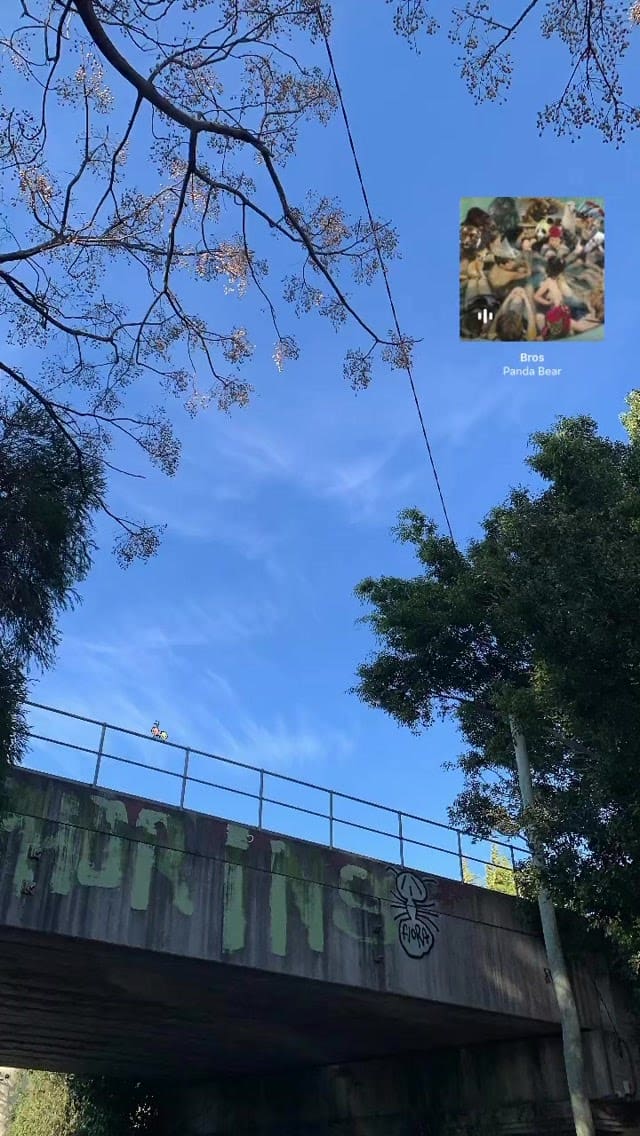

Flora’s wide-ranging oeuvre marks our city, creating a secret network of flora and fauna only visible to the keen eye. Their work ranges from elaborate large-scale multi-colour pieces to vague ant shapes messily drawn on the pavement with industrial glue. The ants sprawl across suburban alleyways, climb up railway bridges and crawl on corrugated warehouse doors.

Graffiti tagging involves using a stylised signature or a series of symbols repeatedly in strategically or centrally located places. It is the most common form of graffiti and has historically been used to indicate presence or ownership of territory. In this fashion, Flora’s tags are most notably saturated amongst inner-city suburbs like Marrickville and Petersham. However, they have also been spotted at bushwalking trails like the Wodi Wodi track at Stanwell Park. At these locations, far and wide, Flora’s ants are immediately recognisable and stand out amongst the hubbub of industrial urban settings.

Flora’s work exists at a crossroad between the urban and the natural. Drawing from both industrial and natural imagery, they express an environmentalist message with an underlying eco-terrorist approach. Eco-terrorism are acts of disruption or destruction made with the intention to hinder activities considered damaging to the natural environment or its animal species. In Flora’s practice, their use of graffiti is a disruption to the built environment of steel and concrete, serving as an ever-present reminder of the Australian bush. The ants face the threat of being buffed or painted over, reflecting how the bush, which is already meagre in metropolitan Sydney, has been sidelined by urban sprawl and gentrification.

In the city, Flora’s environmentally conscious graffiti acknowledges the natural environment as it takes up urban spaces, often identifying and referencing the names of the original biomes of urbanised spaces. Also appearing in abandoned places and the bush, the ants are left as a mark that there was once human activity. However, most remarkable is Flora’s invisible body of work, one that is made up of native bushes that have been guerrilla planted in the empty spaces of pavement nature strips.

Flora’s work showcases an appreciation for the persistence of nature in the urban environment, commenting on environmentalism whilst poking fun at the idea of “pest control” when the true pests are, perhaps, us. Their practice is highly considerate of how the city has been built on stolen land, thus radically vandalising the city is not an egotistical act of self proclamation but a reflection of the pre-existing tug-of-war between the urban architecture and the natural world.

Graffiti artists must consciously consider the world in the development of their pieces, much like how a photographer chooses to frame an image. Graffiti is born out of its metropolitan environment, appropriating urban architecture to subsequently become part of it.

The infestation of ants over the past few years is indicative of how Sydney graffiti artists and writers have begun to experiment with new ways to present their tag aliases within the world, creating a more vibrant and inventive scene. A city has its own unique style and graffiti culture, just like any other underground scene. A symbiotic relationship exists where graffiti feeds off its environment, which is simultaneously marked and characterised by the paint.

A lot of new pieces around the Inner West, Flora included, have a deliberately ‘bad’ style that doesn’t necessarily adhere to the fundamentals of graffiti like letter structure, flow, and colour theory. Rather, many of these new creations embrace absurdity, spontaneity, and imperfection. Colours don’t stay within the lines, the handstyle isn’t technically well-executed — but it’s also a really appealing style, both aesthetically as a playful graphic format and as a resistance against the supposed ‘better’ style of street art murals. Flora’s work epitomises a steadily-growing movement away from traditional street art towards a more radical ‘anti-style’ within Sydney’s graffiti scene.

Anti-style graffiti, also called trash graff or ignorant style, is a strand within graffiti art that is usually considered more playful and impulsive, rather than technical. Although the name “anti-style” suggests a departure from conventions of traditional graffiti, the graphic typeface and freeform letter structures of anti-style stem from old-school tagging styles that emerged in New York during the late 1960s and burgeoned into a “subway graffiti era” of hip hop graffiti throughout the 70s and 80s. some pieces are just as formally complex, requiring decent skill and experience.

Roots of anti-style can also be found in European-style graffiti in cities of Berlin and Paris, but even more so in the Russian scene where “people don’t seem to want to learn to paint beautifully and accurately”. Despite this, there are still formally complex anti-style pieces that require decent skill and experience.

This playful style has amassed popularity amongst internet communities over the past few years, with Instagram accounts compiling with almost archaeological precision a global archive of anti-style graffiti. On the international anti-style graffiti scene, there is @trashgraff, @antistylers; but more locally, @florapest is an account that has started documenting Flora’s work since early August. Dr Lachlan MacDowall, professor in Screen and Cultural Studies at the University of Melbourne, explains how this Instagram phenomenon of graffiti documentation has allowed instances of graffiti to “have longer life and a larger audience as a digital object” that isn’t bound by their ephemerality or hidden locations.

“Instagram is fundamentally reshaping the practices, aesthetics, and consumption of graffiti and street art…they are increasingly produced as digital objects for digital audiences,” Dr MacDowall writes.

Ultimately, the anonymity of the artist is what makes Flora’s work so engaging. The ephemerality and mystery of these smiling ants make a direct encounter with Flora’s work ever so precious. Flora denies us the possibility of turning the artist into a celebrity object, thus allowing the work to earnestly speak for itself and reject commodification. Anti-style is a further radical departure from the elitist protocols within a traditionally high-brow art world.

Our initial desire to uncover the identity of Flora slowly subsided as we came to revel in the experience of coming across their work in unexpected corners of the urban environment. Creating a cult following for Flora on Instagram would be counterproductive to the scavenger hunt style inherent to the distribution of their ants. Flora’s work is a reminder to closely observe our immediate environment, and to live in the real world. Anonymity is integral to the experience of graffiti tagging, whether as the artist or as the audience.

Flora’s work espouses an appreciation for nature through the radical use of the ant as a symbol of resistance. The ant is a hybridisation of urban aesthetics and nature. With its rounded body and power plug face, it embodies kitsch. Like anti-style, the emergence of kitsch correlates with the “lowering of taste among post-industrial urbanised masses, and a heightened capacity for boredom.” The repetition and familiar imagery makes it accessible and appealing to the masses, even to those who don’t usually pay attention to graffiti.

Flora’s anonymous ants will multiply even as our city is in slumber. Staining concrete and dripping down steel, the infestation will persist beyond our time on this Earth.