As I sit here and realise that I am set to become a Registered Nurse in six months, I feel excited, nervous, and then afraid. My placements at various hospitals and my work at the New South Wales Nurses and Midwives’ Association (NSWNMA) have revealed to me much more than what I had bargained for. Another day of COVID-19 is another anguishing moment for nurses and midwives, and every day is harder than the last. Wave after wave of pandemic erodes whatever infrastructure is left, hammering the nail in the coffin of a healthcare system at the brink of collapse.

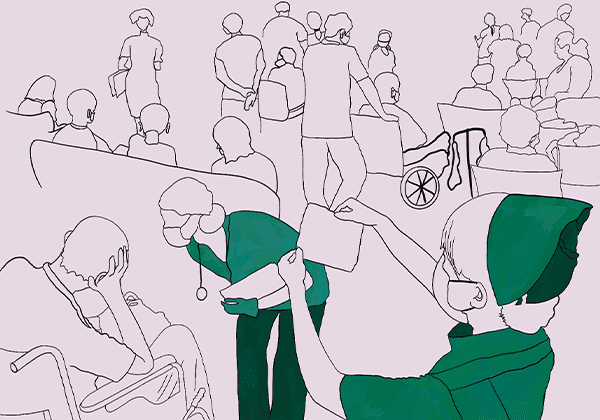

I have witnessed the rushed confusion blurring into the chaos of the hospital, frightened patients tended to by frantic nurses, as it dawns that there are not enough medical staff to keep them safe. No one is safe. Nurses and midwives are overloaded, overworked, burnt out and feeling intense job dissatisfaction. They put their own health at risk every day they are exposed to COVID-19 and fear bringing it home to their families.

Students are doing similar work on placements but are not getting paid for the danger we’re exposed to, offered even less support than paid staff — so essentially, none at all. While you may have seen this in the media, I will tell you the insider’s perspective of the danger that is unfolding in hospitals and what we can do to create a better system. While these issues have been made more apparent by lockdown, they are in reality entrenched issues that have plagued the nursing and midwifery professions for decades. Frankly speaking, nurses and midwives are going through hell and you and your family will be just as affected by this as I am.

Unsafe working environments

Violence in the workplace

At 18, I worked at an Aged Care facility as an Assistant in Nursing (AIN), caring for people who had dementia and were no longer independent. There were no Registered Nurses in the early mornings, leaving just myself and one or two other AINs to help around 20 people. While helping the residents get dressed, eat or change their bedsheets, I was often hit and was even punched once. I didn’t think much of it, but looking back I realise I had experienced something traumatic and was offered no support.

Violence in healthcare is frequent and becomes just another brunt of everyday life. Nursing is the profession at greatest risk of workplace violence. One Australian study found that a quarter of participants reported being physically abused and experiencing sexually inappropriate behaviour. Shockingly, 76% of participants said that they had experienced verbal violence in the past six months. In another Australian survey, 70% of nurses and midwives reported experiences of violence and aggression at work in the past year, and at least 25% reported that it was on a regular basis. The survey revealed that 79% of violent incidents against nurses were instigated by patients and 48% by the relatives of patients. I can’t help but think that if I had sufficient time to tend to over ten people, the residents wouldn’t have felt agitated to the point of violence.

Given 9 out of 10 nurses and midwives are women, workplace violence is a gendered issue that reflects the broader trend of countless, tragic events of violence towards women in society. NSW Health claims to have a zero-tolerance policy for violence and bullying, but this policy is rarely enforced. Dealing with the daily possibility of being harmed is one of the many reasons why nurses and midwives deserve more respect and a higher pay grade. No law or organisation in Australia has gone far enough to prevent violence towards medical staff, contributing to the avalanche of reasons nurses experience fatigue and leave the profession, which ultimately puts our healthcare system at risk.

Absence of COVID-19 Personal Protective Equipment (PPE)

It comes as no surprise that the people most at risk of catching the COVID-19 Delta strain in NSW are frontline workers who encounter hundreds of people, face-to-face, on a daily basis. Medical staff require fit testing, which are masks and other protective items that are more effective at preventing the spread of COVID-19 in hospitals than a regular facemask. While you might assume the government is providing adequate supplies of fit testing equipment to every medical worker in NSW, almost half of nurses and midwives have not been fit-tested.

In my personal experience, as a student on placement and working in COVID-19 vaccination hubs, I have also not been fit-tested, and neither have my peers. Even though COVID-19 has caused the deaths of more nurses than World War I, the plight of nurses continues to fall on the deaf ears of the Liberal government, who are actively making things worse.

Understaffing

More people are being admitted to hospital as disease and chronic illness rates rise in the population but there has been no increase in nurses to match, aggravating the serious issue of understaffing in NSW hospitals.

Currently, public hospitals use a staffing model called Nursing Hours Per Patient Day (NHPPD). NHPPD is used to calculate the amount of nurses needed per shift based on the workloads of individual wards and hospitals. This model has led to inadequate staffing in NSW hospitals for the past couple of decades. One of its disadvantages is that a lengthy negotiation with management is required if more nurses are needed for each shift, usually while staffing levels are unsafe. Often, more staff can’t be rostered due to a lack of funding and qualified staff.

A report evaluating the success of the NHPPD model found that it is sometimes not adhered to, meaning that not enough nurses are rostered to match the perceived workload. Notably, this problem was more common in regional hospitals. The consensus among NSW nurses is that the NHPPD model does not effectively account for patient workload, which creates further issues when negotiating for increased staff when workloads are high.

The main problem with the current model is that it’s not reflective of the rapidly-changing nature of hospital work. I have witnessed Registered Nurses who are rostered to work five eight-hour shifts a week, but have to do at least two double shifts a week just to come back the next morning at 7am, on repeat, with less than eight hours off between sixteen-hour shifts. I have also seen nurses who work three twelve-hour shifts a week and are supposed to have four days off, only to be given two days off, then three more twelve-hour shifts — and their roster has been like this for months. This tenuous situation undoubtedly creates social pressure among nurses as well. If you say no to overtime, you feel that you are letting your colleagues down because they will have a more stressful and dangerous shift without you. Nurses are exhausted and burnt out, with no life outside of work, but if you say no to overtime you are shamed and overlooked for career opportunities.

These problems compromise patient safety. Nurses and midwives have to watch on as their patients suffer, unable to help when their hands and wards are full. When these issues inevitably turn into patient deaths, nurses are often first to be blamed. This has led to nurses and midwives leaving their professions in droves, escalating the persistent global nurse shortage. Faced with unmanageable workloads, the quality of care nurses can provide is reduced, vital medications are missed, and errors are more likely to be made. Understaffing of nurses in hospitals elevates the risk of healthcare-associated infections, pressure area wounds, deep vein thrombosis and mortality. This puts not only nurses at risk, but any person who is unfortunate enough to find themselves in a NSW hospital.

The NSW Health Minister, Brad Hazzard, has stated amongst the catastrophe of the current COVID-19 surge that NSW hospitals are appropriately staffed. It would appear that Hazzard has not stepped into a public NSW hospital for many years. This is not the reality. The system can barely cope. Nurses and midwives have been forced to withstand the mounting pressure on the healthcare system for years. While we are routinely applauded for our efforts, we are completely ignored when we cry out for help.

Possible solutions

Nurse-to-patient ratios

One of the ways to combat understaffing and mitigate violence towards nurses and midwives is staff-to-patient ratios. Only three state jurisdictions in the world currently have legally mandated nurse-to-patient ratios for all nurses: California, Victoria and Queensland. The NSWNMA has pushed for the NSW Government to legally require nurse/midwife-to-patient ratios for decades, yet they have repeatedly declined, claiming that it would be too expensive. This is despite patient ratios in Queensland having been estimated to save $AUD55.2m to $83.4m as it boosted the quality of care provided, resulting in lower patient readmissions, faster recovery rates, and reducing lengths of stay in hospital.

Research also shows that better nurse-to-patient ratios saves hundreds of lives, increases the quality of healthcare received, and significantly reduces burnout. Ratios provide better working conditions for staff, including by reducing the rates of violence, and improving the low retention rates of Registered Nurses. Without nurse-to-patient ratios, anyone in hospital has a lower chance of recovering, and is at a much higher risk of dying or receiving poor care.

The COVID-19 pandemic has shown just how essential nurses are to hospitals, as well as to society. Shouldn’t the government be doing whatever it can to ensure that the most essential workers are well-treated in their jobs? In the last NSW state election in 2019, the Labor Party promised nurse/midwife-to-patient ratios and the NSWNMA supported this promise, however, Labor has not recommitted to this promise. Securing nurse-to-patient ratios is one of the most pressing and important issues facing NSW today. Why is no organisation other than the NSWNMA pushing for it? It should be an issue that every person fights to improve because it affects everyone.

Prestige boost

As mentioned, nurses are repeatedly voted the number one most trusted profession. While polls may demonstrate a high public opinion of nurses and midwives, here lies an obvious discrepancy: how many people know what nurses even do? Labelled as ‘healthcare heroes’ since the start of the COVID-19 pandemic, I am confused by how little the general public knows of what nurses actually do. I cannot count the number of times that I have heard people say “aren’t nurses just doctors’ assistants?”, and “nursing must be easy, all you do is personal care.” “Who could possibly want to be a nurse over a doctor?” said a family member, despite having a sister, a brother-in-law, a sister-in-law and a daughter who pursued nursing.

The reality is that nursing is both as similar as it is different to medicine. If nursing was considered to be a prestigious and important job, rather than the lower tier of the healthcare hierarchy, there would be an influx of students studying nursing which would help rebuild and populate the much-depleted nursing workforce.

Nursing was once considered a trade. Historically, girls would drop out of school and undergo a few years of hospital-based training under the supervision of senior nurses. Note that these nursing students were paid. Now, we pay to go on placement for over 800 hours and even our transport costs aren’t covered. This is another reason less people are entering the profession, because it is hard to perform unpaid work when you have rent to pay.

Nursing was eventually professionalised in Australia in the 1990s, transforming hospital-based training into a university degree. Despite now being tertiary-educated professionals, the lack of status and prestige surrounding the nursing profession hasn’t changed. Contrary to popular perception, nurses don’t follow doctors’ orders. Nurses are led by Nursing Unit Managers (NUM) who are also nurses, while Midwives are managed by a Midwife Unit Manager (MUM). One does not complete three to four years of a university degree to follow orders from someone of a different profession. Instead we work together with other professionals as a team for the common goal of achieving the best outcome for our patients. If a doctor prescribes something and the nurse does not agree, they can refuse and often tell the doctor what they want prescribed instead. In rural areas where there is often no doctor, nurses and nurse practitioners work independently, meeting the needs of patients without a physician.

While people may know that there are nurses with different specialties such as mental health, theatre, or emergency, what is less known is that there are different types of nurses with different qualifications, skills, responsibilities and pay grades. Assistants in Nursing and Enrolled Nurses have completed a TAFE course, while Registered Nurses have graduated from university. Legally, only Endorsed Enrolled Nurses and Registered Nurses can hold the title of nurse. A Registered Nurse, with experience and post-graduate qualifications can go on to become a Clinical Nurse Specialist, Nurse Anaesthetist, Nurse Consultant or Nurse Practitioner; just like how with experience and further education, doctors and allied health professionals can become specialists. Nurses have been taking on advanced roles for decades with no change in public perception. Disregarding the pay difference, it is deeply wrong that nurses are still not treated with the same level of respect as even a newly graduated medical student.

Despite the token appearances of ‘healthcare heroes’, public opinion of the ‘lowly nurse’ has not been swayed. Whatever achievements held in our name, in our duties or our diligence, are seen as an extension of other medical professionals, when in reality, it is the nurse that touches the life of the patient, ensuring compassionate care is given always. So much of our respect for people is culturally ingrained and determined by persistent misogyny in society. It’s partly because nursing and midwifery are still female-dominated professions and medicine is still male-dominated that nurses and midwives are cast in a more servile and less qualified light. I long for the day where a nurse is seen as just as intelligent, qualified, and experienced as a doctor and is given the same respect.

Improved pay

Prestigious professions are more likely to have larger salaries. Despite being essential to society and directly impacting everyone at some point, nurses are not regarded — or paid — as highly as doctors, engineers or lawyers. It is obsolete to argue that female-dominated professions like nurses are not qualified enough to deserve a higher salary. You could argue that an engineer is employed privately in a profitable company and therefore makes more money than a nurse in the public system. But nurses can also be employed in multimillion-dollar private organisations, and still don’t get paid the same amount as those engineers. Yes, nurses earn more than the average wage, but when we take into account what nurses do and the sacrifices we make, does a nurse’s pay truly reflect their qualification, knowledge, capabilities, and the risks they are exposed to? Could a more competitive salary attract more people to the nursing workforce to help combat understaffing?

I appreciate the effort to push for more women in male-dominated fields, but why has there been no effort to improve the pay and prestige of female-dominated professions? Or even to push for more men to enter these professions? Women are not and should not be content with accepting lower wages.

Public support

Issues facing nurses and midwives will only change with pressure, not just from the NSWNMA, but from the entire public. We need your help and support in making hospitals safe for you and your loved ones. Join your union and advocate to support the NSWNMA’s campaigns. Educate your family and friends on the issues that medical staff face and how this is fuelling the demise of the healthcare system. Pressure the government to protect, invest, listen to and support NSW hospitals, nurses and midwives. Write to your local MP, share these issues on social media, tell a nurse and/or midwife that you understand what they have been dealing with for decades. Follow the NSWNMA and join the nurse-to-patient ratio campaign once lockdown is over.

I urge you to join us because nurses, midwives, students and patients are suffering in a system that is supposed to keep them safe. The government refuses to risk reaching out their hand to help, not for fear of contracting COVID-19, but content at the steady demise of health workers and patients. We must take action. Nurses and midwives have had enough of this treatment and of being cannon fodder in the Liberal government’s crusade to ruin public health in the name of economic management, when they are possibly the worst economic managers Australia has ever had.

***

I am frightened to graduate into a profession where violence and burnout are part of the job. I’m even more fearful that opening up our borders next year will turn our already crumbling healthcare system to rubble, and that I will be present to witness my patients caught in the wreckage. Even people without COVID-19 will die if there is no change now. This fate is inevitable within a matter of months. Nurses and midwives chose these professions knowing about the sacrifices we would have to make, but we urgently need safer workplaces and increases in pay and prestige, which would address the shortage of nurses.

When these changes are finally achieved, I can confidently say that you would be given the best possible care if you ever found yourself needing medical help.