Walk along the busy pavements of Sydney’s Chinatown, Hong Kong or Shanghai on Lunar New Year and one will likely be greeted with ample sightings of an iconic dress — the Cheongsam. Hitch a scooter down south to Hanoi and a remarkably similar Ao Dai reigns supreme. Although seemingly distinct, both owe their history to 17th century monarchism, 1920s colonialism, and a changing 21st century. The dresses have come to represent the struggle between feudalism and modernism, hedonistic capitalism and the proletarian, and not least feminism.

Starting with its etymology, Cheongsam (長衫) and Ao Dai literally translates to ‘long dress’ in Cantonese and Vietnamese. Albeit in Mandarin Chinese, the cheongsam also goes by qipao or ‘gown of the banner people’ – an explicit but since ossified reference to the Manchurian origin of the dress. In the mid-17th century when the Manchurian Qing Dynasty seized power in China, edicts were passed around the country to suppress practices associated with the Han majority population. According to Jujuan Wu in Chinese Fashion from Mao til now, sanctions included summary executions and fashion became a proxy for identity politics:

“The Manchu wielded this weapon as a means of imposing their authority while the Han clung to their own clothing styles as a means of resistance.”

China was hardly alone in imposing such edicts. Indeed, in Vietnam, Nguyen Phuc Khoat enforced strict rules that conformed to Chinese fashion, mandating long Manchurian robes among his mandarins.

It is perhaps ironic given this history that both the Cheongsam and Ao Dai emerged as nationalist icons as both are arguably, quintessentially Eurasian garments. The Cheongsam, for instance discarded the comfortable free-flowing form of its predecessor the Changpao in exchange for a fitting, slim silhouette. Coinciding with the belle epoque and feminist liberation that followed the May Fourth Movement (1919-21), the social acceptance of individualism and Chinese patriotism consolidated the early cheongsam’s status as “the formal dress of the Republican Era”.

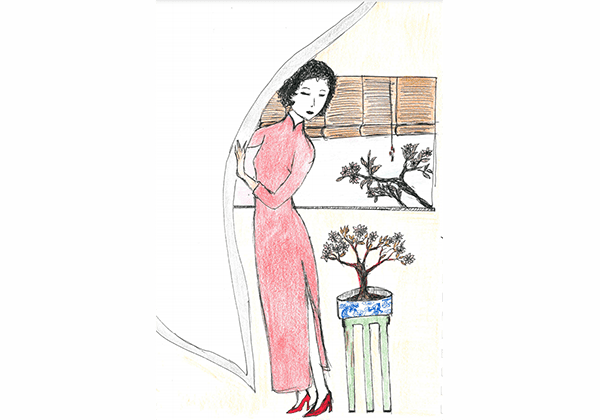

Despite cheongsam being a Cantonese word, according to Cheryl Sim, it is best thought of as historically Shanghainese and Hong Kongese. Prior to the Cultural Revolution, the cheongsam was synonymous with the hedonism of these major cities – picture Suzie Wong (Nancy Kwan) in The World of Suzie Wong (1960) dancing in a scarlet red cheongsam in Wanchai.

Simultaneously, the Ao Dai experienced its own reformation when Nguyen Cat Tuong or Lemur, an artist trained in the colonial Ecole Superieure des Beaux-Arts de l’Indochine modified its predecessor (the Ao Ngu Than or five-panels tunic) by eliminating the fifth panel in favour of a formfitting single outfit that highlighted the chest and waistline. In a 1934 column in Tuan Bao Thanh Hoa (Thanh Hoa Daily), Lemur penned his proposal for a unified Vietnamese national costume – the Ao Dai:

“Even though clothing is used to cover up the body, ultimately, it can be the mirror that reflects outward a nation’s level of intelligence,” Lemur opined. He rejected the prevailing winds of feudal conservatism in favour of a distinctly Confucian garment that embraced capitalist modernity.

“To know which nations have progressed and have a high aesthetic sense, just look at the clothing of its people. No matter what, it must have the characteristics of our nation.”

Implicit in Lemur’s case was a call for Vietnam to fully embrace the capitalist modernity that defined the belle epoque of the 1920s. In many ways, Lemur’s echoes French colonists’ view of Vietnam, having assigned Saigon the Latin motto “Paulatim Crescam” – literally meaning “little by little we grow.” For Lemur, the Eurasian form of the Ao Dai was never coincidental, it was a deliberate assertion of Vietnam’s relative prestige in the French Empire.

These changes, however, did not arrive without backlash as both garments were perceived to be a degradation of Confucian social mores and symbolic of Western decadence. One column in a 1935 edition of Saigon’s Ngay Nay noted an incident where two young womens’ Ao Dais were compromised by a middle-aged woman. The paper noted that such incidents were motivated by an unease that the Ao Dai had eroded traditional Vietnamese social structures. Yet, in the decades that followed, the dress quickly became a national icon representing formal elegance and idealism, as the white Ao Dai became inseparable from high school naivety.

In China, the cheongsam was briefly banned following Mao’s Cultural Revolution because the dress was deemed bourgeoise. Indeed, Wang Guangmei, wife of then- PRC President, was heavily criticised for wearing one on a delegation to Indonesia. It was not until the 1970s, with Deng Xiaoping’s economic reforms, that the dress gradually re-entered public consciousness.

It is thus remarkable that these dresses, once decried as Eurasian impositions on colonised populations, have become iconic symbols of women in China and Vietnam. Their turbulent stories are a testament to the dynamic forces at work in fashion. Above all, their evolution – from an imperfect colonial emergence, through prohibition, and then on to become nationalist icons – represents the vicissitudes that arise as contradictory social impulses vie for prominance and negotiate core values.

Today, the Cheongsam and Ao Dai remain in flux, having evolved from their conservative beginnings to become critical players in 21st century fashion– batik, cut-out or draped in splendorous lace.