In the original 1976 Homo Soit, an article called Gay Studies written by Dennis Altman speculated that “In a University as academically conservative as the University of Sydney it is probably utopian to even talk about gay studies.” Yet surprisingly, Altman does not go on to argue for gay studies — at least not as an academic discipline in isolation — even questioning whether it is “an area of great importance.”

While acknowledging that Monash and Flinders Universities had some form of gay studies, and the agitation it took to win a feminist philosophy course at USyd two years prior, Altman argued that more relevant than lobbying for gay studies was to counter the present moralising attitudes toward homosexuality in courses like law, medicine and education. His main concern was that a course on gay studies would be too insular, leaving “untouched” the distorted perception of gay people in wider society.

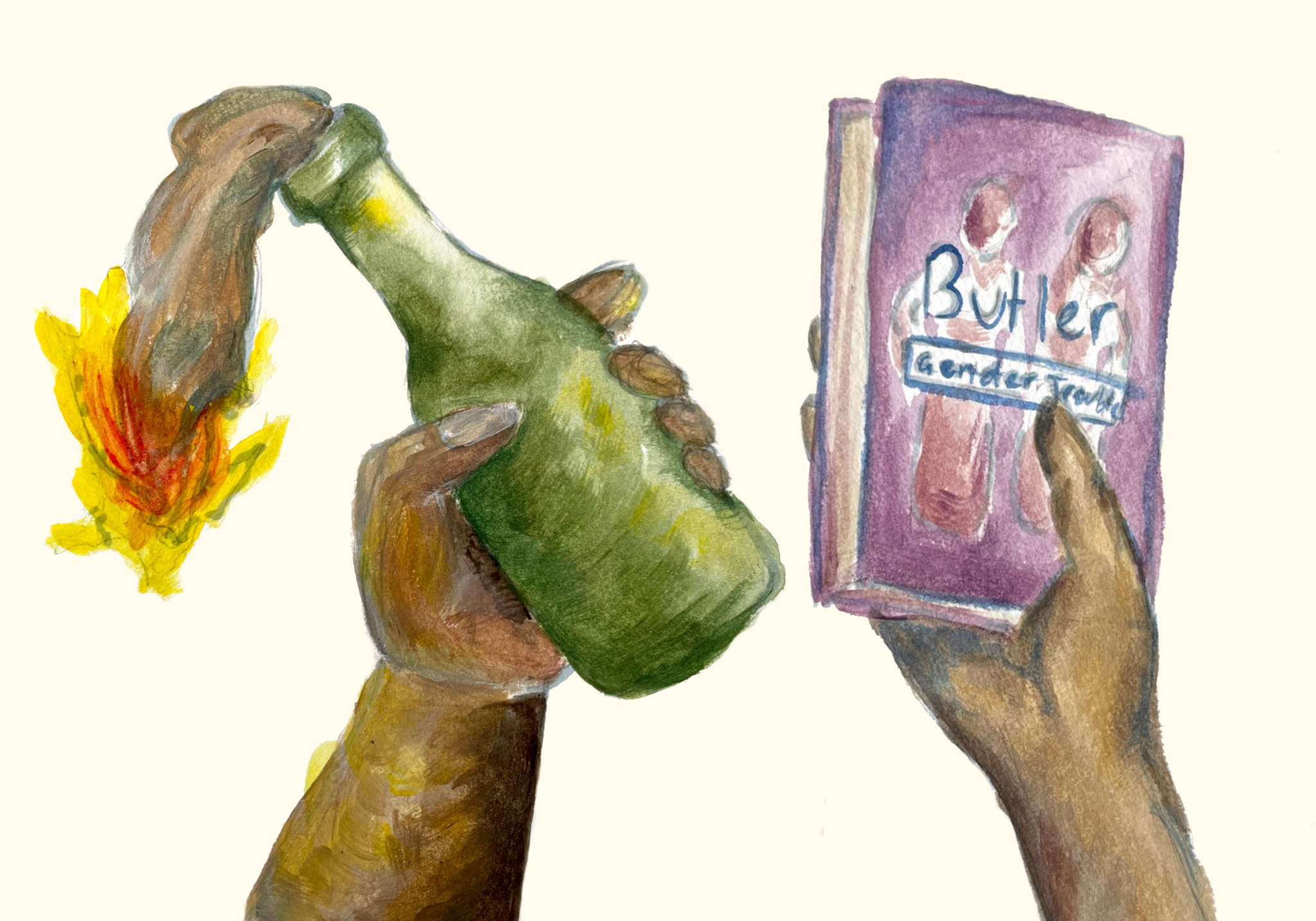

45 years later, gay studies is no utopian horizon but a reality at the University in the form of queer theory, taught in the Department of Gender and Cultural Studies and exerting an influence on most Arts courses. My English degree introduced me to thinkers from Michel Foucault, Judith Butler, Eve Kosofsky Sedgwick, Lauren Berlant to Jack Halberstam; the countercultural queer theorists I read were among the most transformative for my view of the world and literature.

However, as we face the ever-increasing corporatisation of higher education, the question must be asked: what is queer theory’s relationship to the University’s constant institutional violence, inflicted by casualisation, course cuts and surveillance? Has its marginal and oppositional status — the political radicalism denoted by ‘queer’ — been domesticated with its popularity and its position within the ivory tower? What does the existence of queer theorist university bosses indicate about the field’s proclivity for co-optation by the mainstream?

Attacks from outside academia in the culture wars would seem to suggest that the marginal status persists; that queer studies and other fields of critical theory pose a continual threat to conservatives. In How To Be Gay (2012), David M. Halperin recounts the typical shape of this hand-wringing rhetoric, writing that “others have long suspected that institutions of higher education indoctrinate students into extremist ideologies, argue them out of their religious faith, corrupt them with alcohol and drugs, and turn them into homosexuals.”

Regardless of what conservatives’ long standing fears suggest, radical thought faces the looming threat of extinction within universities, where social problems are commonly approached through a cushy, individualist, vocational lens. The introduction of compulsory Industry and Community Projects Units that suggest we can solve ‘real-world problems’ like sexism through short-term group projects has eaten up space in our degrees that were once for theoretical units and electives. Universities are prone to treating queer studies as mere fodder for vocational diversity training modules, encouraging the next generation of workers to believe that the capitalist economy can be mended through diversity. This is not the fault of staff per se but a structural problem of institutions where everything must be justified under the banner of profitability, while an axe hangs over staff’s heads through endless restructures.

The relationship between detached academic theorising about social movements and the embodied knowledge produced within those movements has long been a contested one. Queer studies is not inherently revolutionary, especially not in isolation from analysis of class or race. During the heyday of post-structuralism, queer studies was dominated by critique — a humanities-wide project characterised by a suspicious style of unmasking texts for symptoms of deeper power structures. Critique staked a claim to being the only politically radical method available, yet its methods have since attached themselves to views across the political spectrum, mutating into everything from climate change denial to anti-vax movements.

Nearing the turn of the century, essays like Sedgwick’s Paranoid Reading and Reparative Reading (1997) began self-questioning queer studies’ beholdenness to critique. Sedgwick suggested that a demystified view of oppression gained through critique — or paranoid reading — did not necessarily enjoin one to take action, suggesting we take seriously pleasurable and affirmative modes of reading as well. Moving towards embodied approaches to interpretation that inspire hope rather than mere scepticism, the line of reasoning went, could better conceive of imaginative possibilities beyond the current state of things. Likewise, in The Militancy of Theory (2011), Michael Hardt suggested that critique’s ‘melancholic’ disposition made it insufficient to “transform the existing structures of power and to create alternative social arrangements.”

Abstracted from the terrain of political struggle and situated within neoliberal institutions, queer theory can be a demobilising force rather than a revolutionary one. The 21st century turn towards postcritique — finding new modes of reading beyond ideological criticism — has recognised the limits of critique yet fallen into similar political stalemates. When framed as a response to the denigrated humanities, postcritique risks capitulating to conservative demands of universities to be ‘uncritical’. FASS Dean Annamarie Jagose’s lambasting of “the clear-eyed, all-knowing, hermeneutically suspicious position of the protestor who sees through the spin” is direct from the discourse of postcritique — a case in point for how the turn away from critique can sometimes be a reactionary one.

One issue with postcritique is that its attention to affect plays into the individualist logic of neoliberalism when the larger political context is disregarded. As students schooled in queer theory, we must interrogate what it means to turn from the collectivistic to the individual, from the philosophical to the vocational, and what impact theory has on political engagement in the world. For one, it should motivate us to fight against the current proposed changes to Gender and Cultural Studies at USyd that threaten the autonomy of the Department; even the smallest chipping away of the field can set a precedent for future decline.

As we become entangled in our commitments to individual research projects within the University, we can lose sight of the life-or-death stakes of the collective struggle that our research concerns. The perception of queer studies as insular and parochial continues, particularly when situated within institutions inaccessible for many. But queer studies can be political work and it can compel us to go out on the streets and fight for queer liberation; and secondly, for a university where theory doesn’t just radically anticipate a better world in an abstract sense but is part of the work creating it.