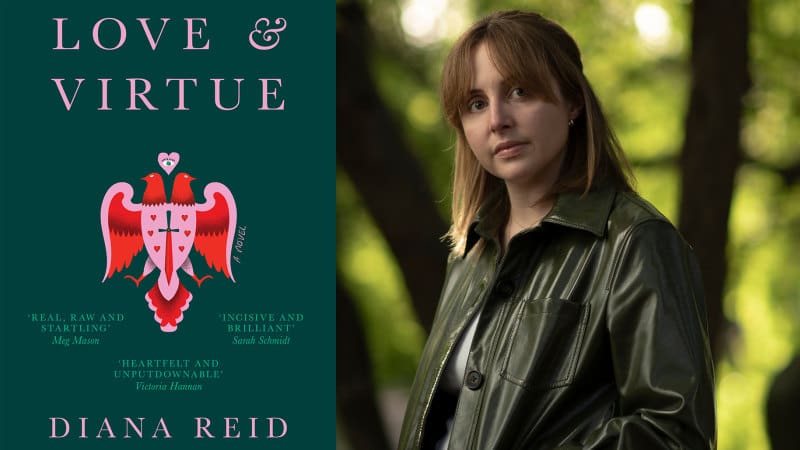

Wounded by the growing sense of distance that we currently feel from a so-called ‘normal’ campus experience, we flock to fiction to get our quick fix. We chuckle at the familiar awkwardness in Elif Batuman’s The Idiot, lament in the melancholy of John William’s Stoner, are frustrated by the tumult of Sally Rooney’s Normal People and are perplexed by the mystery of Donna Tart’s The Secret History. But despite more people going to university in Australia than ever before, the national contribution to campus fiction is surprisingly paltry. Recent University of Sydney Philosophy and Law graduate, Diana Reid’s debut novel, Love and Virtue, intends to fill this gap, taking readers into the elite world of residential colleges at a fictionalised Sydney university.

Protagonist Michaela is a high-achieving scholarship student from Canberra, who is a resident at the fictional women’s-only ‘Fairfax College’. Arriving during O Week, her welcome to Sydney is fuelled by copious amounts of alcohol, ending in a non-consensual sexual encounter that becomes a thematic centrepiece in the text. Her best friend and college neighbour Eve is the picture of perfection – almost too smart and too beautiful to be human. However, their relationship exudes a Ferrate-esque competitive streak that manifests in various instances of toxicity and betrayal.

Whilst in conversation with Honi, Reid acknowledged that such a portrayal may not be particularly good for the ‘sisterhood’, she believes that it is vitally important to depict characters that are real. But more than this, incumbent in the persistent competition is a sense of self-respect. Both Michaela and Eve are characters who are powerfully driven, their competition grounded in a will to be independent and seek academic validation, rather than a spat over a man. In this way, their rivalry is an empowering expression of female ambition, and a show of respect for their opponent’s talent and intelligence.

University stories tend to be dipped in a familiar slew of clichés, their characters serving as exemplars of recognisable stereotypes. Love and Virtue embraces this trend quite plainly, but not always to a fault. Reid often toys with these tropes to build up readers’ expectations, developing the archetype only to slowly dismantle it as the text unfolds. This is most clearly the case in the portrayal of Professor Paul Rosen, Michaela’s first year philosophy professor.

Professor (‘call me Paul’) Rosen is deemed immensely likeable, despite his visual portrayal being rather unflattering. But still, the expectations surrounding his character are firmly grounded in the social narrative concerning his position as a professor – grounding him in the pomp and status of the institution, and accentuating his personal authority derived from being both male and white. Nonetheless, when the spark between Professor Rosen and Michaela finally develops, the result appears inconsequential – their romance fleeting, reciprocal, and in many ways, quite normal.

The anti-climactic nature of the relationship would prompt many to ask: What was the point? When reading the text, I honestly thought the same. However, in conversation with Honi, Reid proposed that this relationship serves as a parallel to that between Michaela and Eve. Although the same age and gender as the protagonist, Eve is highly manipulative, often to Michaela’s detriment. However, the manipulation reveals a prominent grey area in the realm of moral decision making, as it lies outside of the principally grounded power dynamics within the social imaginary, such as that between a man and woman, student and teacher. This reflects the ultimate aim of Reid’s text: to compel the reader to go beyond the assumption that there is always a black and white answer, and realise that things are so much more confusing than they seem.

But the most morally troubling part of the text arises from a tension in Michaela and Eve’s relationship, as Eve takes Michaela’s story of being raped during O Week as her own. Spreading the story at social events, in the student newspaper, and ultimately, writing a book about the event, Eve gets to be the martyr without any of the suffering.

In the shadow of Chanel Contos’ online publication of sexual assault victim testimonies, Reid’s book is particularly salient. However, in my view, Love and Virtue takes the conversation a step further. By paying close attention to the optics of sexual assault rather than the instance itself, Reid highlights some of the moral and emotional troubles that victims face when coming forward with their stories. But perhaps more importantly, she leaves the reader asking, why, when there are so many people suffering, must we always make the story about ourselves?

I started this review by proposing that campus fiction fills the void left behind by the lack of a ‘normal’ student experience. With this thought, I am drawn to the words of Iris Murdoch:

“We live in a fantasy world, a world of illusion. The great task in life is to find reality. But given the state of the world, is it wise?”