In Amsterdam, the moon is unpredictable. Humans may have attempted to govern and explore it, and dictate its wax and wane, but as Winter subdued into Spring, I found myself searching for the moon later and later at night. Sometimes, it would rear its haloed head, anchored against an often starless sky. Other nights I missed its presence completely. Maybe I forgot to look for it, too distracted by life in a foreign city, but I preferred to believe the celestial being had a mind of its own, and maybe it just didn’t feel like showing up.

The moon’s place in literature dates back as early as the 10th Century, where a Japanese folktale called the Tale of the Bamboo Cutter first depicted the moon as an inhabited planet —- not quite Earth but an early science fiction interpretation of an alternative existence. The moon was popularised by the Romantics. Shelley, Coleridge, Yeats and Wordsworth were all fascinated with this “silent moon”, a symbol easily manipulated in their prose to represent everything from the measurement of time, to love, virginity and metamorphosis.

During my studies in the city of bicycles, I read Charlotte Brontë’s lesser-known work, Villette. The Gothic novel centres around a young governess Lucy Snow, and her life in the fictional town of Villette (likely based on Belgium where the author spent time teaching).

For Brontë, the moon shone a light on the tension between feminine moral righteousness and expression, passion and emotional freedom. It was used to explore the social repression that the Brontë sisters were familiar with, whereby women were forced to restrict imagination and feeling. No example is more demonstrative than the fact the sisters could not publish their work under their own names.

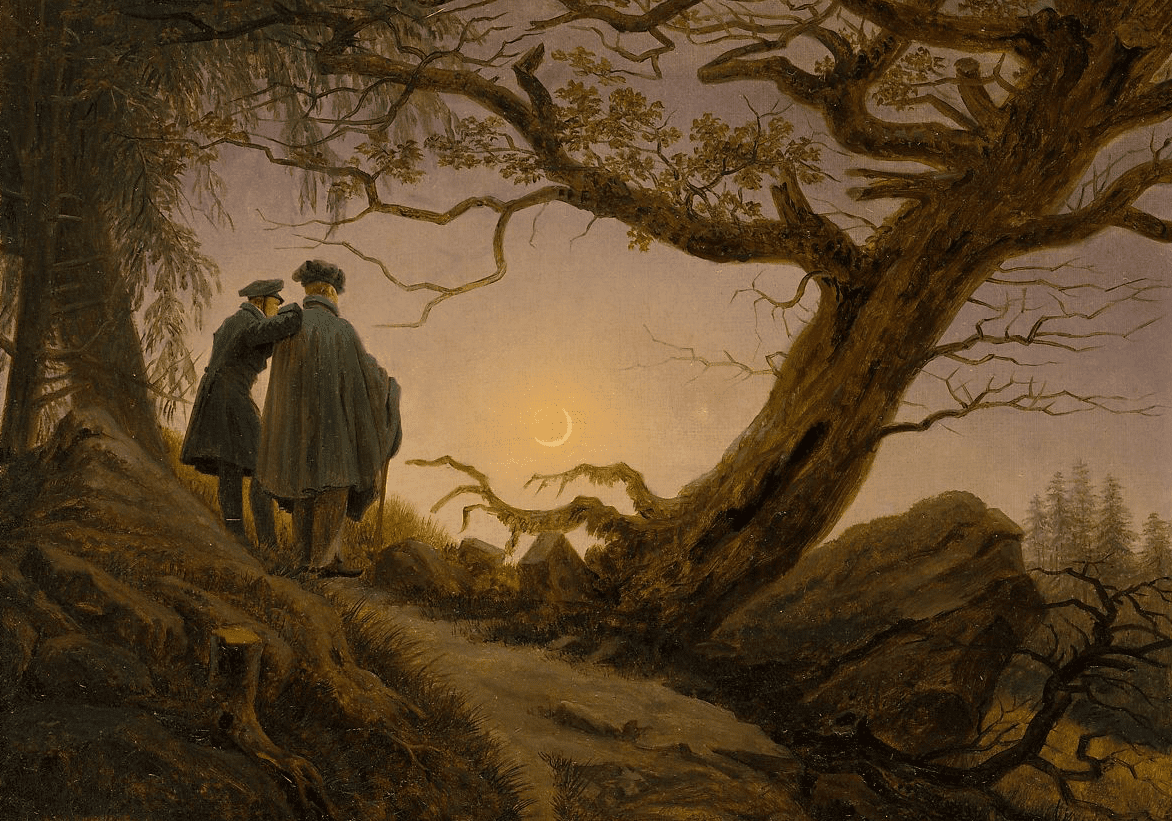

In Villette, the moon links to all that is irrational, conjuring up childhood tendencies of expressiveness and reflecting Lucy Snowe’s inner conflict as she chooses logic over the self-fulfilment of her own inner desires. “A moon was in the sky, not a full moon, but a young crescent… she and the stars… my childhood knew them… Oh, my childhood! I had feelings”. Anything less of mind is attributed to ‘female hysteria’, which she is countlessly diagnosed with by her love interest Dr John throughout the novel.

The moon has long been linked to femininity. In history, Homer associated the moon with Greek and Roman goddesses such as Artemis, and in etymological patterns the Greek root of “Selene” and Latin root “luna” both have feminine endings. Brontë uses this classical tradition to her advantage, the pronouns ‘she’ and ‘her’ describe the natural figure throughout the work, “Rosy or fiery, she mounted now above a not distant bank; even while we watched her flushed ascent, she cleared to gold”. The novel’s first-person narration allows meaning to be read into Lucy’s own observations and descriptions. In fact, Kathrine Gillman wrote that “much of the natural symbolism evident in the text is a product of Lucy’s… attempt to give inner form and expression to the emotions she tries so hard to suppress outwardly.”

Although the novel mainly keeps to its critique of Victorian social norms, one particular human trait transcends its pages. Brontë brilliantly captured the tendency for nighttime to unleash a transformation of the self, injected by recklessness and the adventure that lies behind the shadowy darkness.

When you don’t yet know the city you are living in well, night brings with it a new challenge. Navigating cobbled, narrow streets once familiar in the day, become disorienting but leave space for the unexpected. Exposure to new substances probably didn’t help; Jäger, anonymity, new friends and you can guess what else, created a cocktail of uncertainty, yet the unknown made it invigorating. A hidden canal glittering with reflections of neon signage, away from tourists or a tawdry rock n’ roll themed bar with an interesting clientele would never be stumbled upon in sunlight.

I’ll never know how rowdy Bronte got herself after a couple glasses of sherry, but under a “dubious light,” her protagonist experiences a similar nighttime epiphany to one’s I’ve had myself, she demands that “this night I will have my will”. In a drugged-state, Lucy ventures out to a fete and follows the “ebb” of the crowd. Once lost and “outshone” by other lights, her pivotal turning point towards inner peace is now clear, “the rival lamps were dying. She held her course” under a “calm and stainless” moon.

As I read Villette, I realised the moon metaphorically guides not only Lucy’s way, but also my journey as a reader. It made me grateful for the ‘irrational’ women on the pages, and perhaps, it helped me justify my reckless, emotionally driven decisions on a night out, at least just a little.