Screening from the 17th of February to the 3rd of March, the Sydney Mardi Gras Film Festival showcases the biggest and best LGBTQIA+ cinema the world has to offer. The organising body, QueerScreen, emerged from the grassroots, just like the Mardi Gras festival itself. In protest of heteronormativity in the film industry, a group of queer Sydney students, filmmakers, and supporters founded QueerScreen, which has run the festival since 1993.

Advertising for the festival takes many forms, but the most visible is the posters that are plastered about the city. How organisers advertise a film festival says a lot about the festival itself and the movies they screen. Posters for the Sydney Film Festival or the Underground Film Festival feature images and iconography that indicate the experiences you may have. One festival might feature bright, poppy visuals safe for general audiences, while the other confronts you with strange bodily transformations and weird nightmarish creatures.

The Mardi Gras Film Festival sets itself apart from its contemporaries with a history of posters that are more thematically complex. These posters often question the category of ‘the human’ in regards to queerness, with bodies organised in space in various ways interacting with technology or each other, and sometimes an absence of humans altogether.

These creative choices point to a trend that film theorist Karl Schoonover discussed in the journal Screen. He suggests queer film festival posters exchange LGBTQIA+ humans in favour of “avatars of queerness”. These avatars range from robots to animals, anthropomorphised objects, or bodies lacking distinct human characteristics. For Schoonover, this imagery and their absence of the human forces us to “consider how LGBT politics figures the human and how the queer appears in international human rights debates.”

Amid the 1990s, large scale international movements to decriminalise homosexuality gained geopolitical traction under a human rights framework.

Article 2 of the 1948 Universal Declaration of Human Rights designated that certain groups were particularly vulnerable to rights violations. Yet it does not mention LGBTQIA+ identity anywhere. Fortunately, later revisions in 1966 and throughout the 1980s and 90s have attempted to mend this. The negation and later addition of sexual orientation and queerness as categories point to the turbulent fight for recognition.

As Schoonover notes, “while stating that there are no distinctions within the category of the human, the Declaration points to existent distinctions.” When LGBTQIA+ people have once been excluded from this definition and later added, the Declaration creates a division between those who are assumed to have always been human, and those who need their humanity to be affirmed by the previous group.

Schoonover suggests this human rights discourse is made manifest in the non-human configurations of queer film festival posters, which can be organised into three iconographic subsets: avatars, objects, and animals. The Mardi Gras Film Festival has adopted each over its nearly 30-year run.

‘Avatars’ are figures tenuously tethered to the human, often indeterminate and indiscriminate bodies silhouetted or modified somehow. These bodies remind observers of some physical transcendence of personhood itself, whether it be a superhero striking a pose, some sci-fi or fantasy figure, or a cluster of astronauts with their faces obscured. These posters reduce the “particularities of the body to universalise the identity of the queer”.

Many Mardi Gras Film Festival posters feature these indiscriminate bodies and their transcendence from physical form, often through interactions with the technology of film itself, such as the 1998, 2002, 2006 and 2007 posters. Schoonover asserts that these “composite creatures evoke a technophilic futurism” and a dissolution of the human/non-human binary.

“Avatars of queerness” in the posters for the 1998 and 2007 Mardi Gras Film Festival.

The second group, ‘objects,’ extends this notion of a departicularised human form by abandoning the humanoid altogether. Groupings of objects of various colours, shapes, and sizes suggest queerness is emerging en masse, identified by likeness yet accommodating to difference.

This can be seen in the 1997, 2005, 2008, and 2010 posters. Congregations of objects such as film reels or popcorn kernels evoke the bold pluralism and inclusivity of the festival, as a space devoid of gendered or racialised bodies and categories of the human.

A mass of objects compile and converge to form a whole unit in the 1997 and 2008 posters for the festival.

The final category, ‘animals,’ has only been recently used in the 2020 poster of a multicoloured butterfly. Schoonover suggests this is another way of universalising these nonhuman figures, representing LGBTQIA+ people as animals rather than humans. This, coupled with the slogan “Evolve. Emerge. Fly.” signifies the festival’s metamorphosis into this final category, abandoning any attempts to configure the human at all and transcending out of the limbo of human rights discourse.

2020 Mardi Gras Film Festival poster

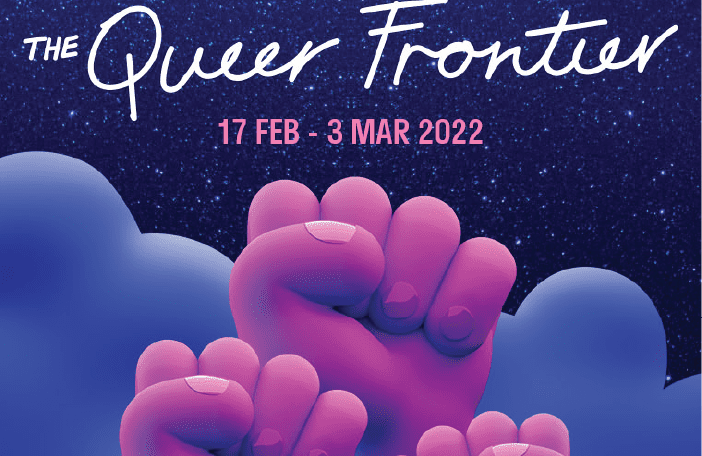

The 2022 Mardi Gras Film Fest poster continues the tradition of dissolving the body and queer’s shifting relation to humanness. Featuring a trio of raised fists, their cartoony, non-descript designs lack any signifiers of race or gender, emphasising the plurality of queerness and its recurring negation and affirmation in human rights discourse.

For Schoonover, the ironic negation of the human from queer film festival posters is a liberatory act of reclaiming one’s humanity and acts as a radical rebuke to a human rights discourse that is constantly tripping over itself to accommodate the LGBTQIA+ community.