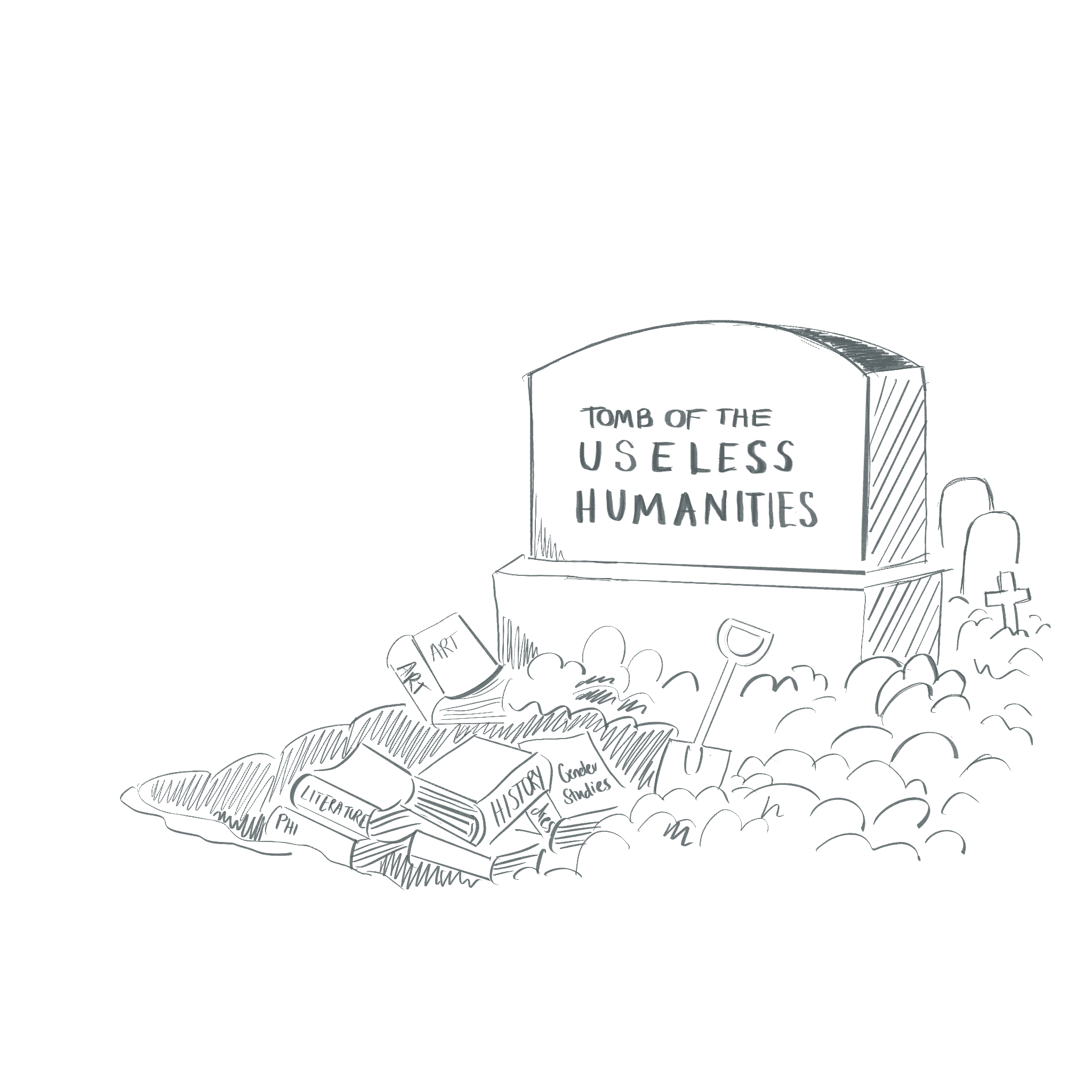

In today’s highly corporatised university landscape, knowledge has succumbed to capitalism’s utilitarian logic. The ‘usefulness’ of a subject is no longer judged by its potential to contribute to the common good but by its value in the job market.

Poetry, art, culture, education, and even science— everything that should not be commodified has been by this logic. ‘Useful’ knowledge is determined solely by the anticipated economic benefits that it may bring to capital or industry. Employability, return-on-investment rankings, career readiness and even the egregious Job-Ready Graduates package in 2020 are all aimed at subjecting education under this fetish for efficiency.

As long as capitalism is the dominant way of our lives, the humanities will continue to be regarded as ‘useless’. Yet they remind us that human beings are not merely means to an end; instead, the best of the humanities radicalises and agitates against the status quo. Although the humanities may contribute to less ‘practical’ knowledge, they nurture the seeds of social change by interrogating our assumptions time and time again.

Medicine, biology and engineering may be deemed more useful with life-changing implications, from modern prosthetics to John Snow’s defence of Germ Theory in the 19th century leading to mass reductions in cholera. However, the humanities also have their fair share of momentous contributions in social advancement. It was the Communist Manifesto that ignited proletarians to strive in class struggles, just as it was Martin Luther King’s condemnation of White America that united African-Americans in the civil right movement. It has always been these seemingly ‘useless’ dissents emanating from each generation that has driven progress.

Ethics question the illusion of happiness in modern society. Literature teaches young poets not to acquiesce to life, but to rage against the dying of the light. Queer history inspires generations of student activists to take up the fight against the repressive governments. Not to mention the fact that the ‘useless’ humanities have given rise to cross-disciplines such as bioethics and environmental economics, which in turn have benefited our implementation of technology and productivity.

On the other hand, the seeming dominance of capitalist discourse has made it increasingly impossible to imagine a different form of life. Today, we can no longer even imagine a life beyond comfortable self-exploitations, a life defined by freedom and personal fulfilment. Under the status quo, an alternative vision will likely be dismissed as naive yearning for utopia and scorned as unrealistic. Deprived of the ‘useless’, we have long since lost the ability to imagine, understand – let alone explore – the vast possibilities offered by the humanities to live a more genuine, freer life.

Writing fictions in ENGL2666 might not immediately pay your bills nor appreciating Wong Kai-Wei’s Fallen Angels in FILM1000 would help you stand out in business interviews; however, literature and films expand the boundaries of our personal experience, reminding us that the complexities of being human could never be reduced to a mere factor in economic calculation. They allow us to experience the world, to feel the human condition, to struggle, to compromise, to rejoice, to grieve. They revive our kindness, imagination and innocence that have been long alienated.

It is precisely these ‘useless things’ that keep telling us that we are a being more than ‘useful’: they keep us alive.