—Track 1—

The first choice was automatic—

Bụi Phấn, a moral message disguised

as a children’s song.

It speaks of nostalgia,

the very thing it now generates.

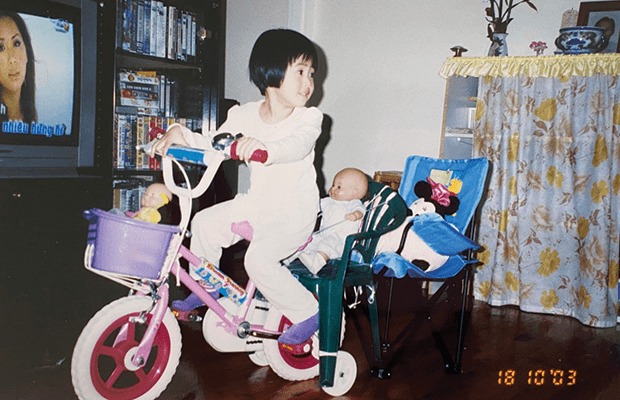

In the distant past, I sang it with my father,

guided through fluctuating tones,

the octave leap connecting verse and chorus,

his swaying to the oom-cha-cha. It was

a seated waltz. I knew

the poetry without translation. I felt

the way he did it smiling.

It never bothered me

that the question I had back then

was never answered.

Was it white chalk in his hair

Or was he getting older?

I was too young to know what a metaphor was

but I could recognise, feel one.

I learned that everything is secretly something else.

What I failed to understand was that nothing

could stay as it did, that it was a tune I would sing less

far too soon.

—Track 2—

The first game of hide-and-seek I played

was with my voice in someone else’s house.

My father gestured towards the television

and passed the remote with all its bulging buttons to me.

Although the endless scroll of queued tracks,

panoramic stock images

of what I imagined was countryside Vietnam,

and the shuffling lyrics filled with colour

were sights I was wholly acquainted with,

his request for me to sing was unsettling.

He knew only the enthusiasm at home

for the music we shared,

not the children’s accusations —show-off,

not the parents’ concerns —what potential wasted potential,

not my eyes desiring to close like shutters

and stay fixed.

I leapt over those hurdles of murmurs,

grabbed the remote and chose Hero,

to say “This is what I am capable of”,

“I am more than these childish songs”,

“I am fine with this.”

—Track 3—

The first karaoke bar experience I had was during an after-party.

I came after a faux wedding, a masquerade with everyone

in fancy dress, wearing fake grins.

They screamed to a song about taking what they wanted,

about making dollars, how much fun they were having.

but earlier, they whispered about the bride’s self-interest,

about how the whole affair was easy money, how much fun they were having.

I was reminded of where I stood,

of where I was lucky to stand.

My father told me I was lucky, but I never knew that it meant

lucky to be born here and not across the ocean,

lucky not to be in a constant battle with permanent residency as the temporary prize,

lucky to have the freedom that those with the same surname and hunger as me

must relinquish to afford.

And yet, despite the fact that I was lucky, I did nothing with it.

When I arrived home, my father attempted to learn about the night,

his usual

What did you get up to today?

So did you get up there on the stage this time?

Did you have a good time?

They were each met with less than three words.

I spared my father the details

but wondered what he would have done.

Maybe laughed and agreed

how lucky she was to have found someone willing to make this transaction,

or perhaps he would have called them out, made them doubt the morality,

of the entire situation, of the truth they were speaking.

At least he would have reacted.

I sat there, a microphone in one hand

and with the other opened, ready to catch,

snatch their words and release their power right back.

All I did was let them slip through

and pile on the ground.

—Track 4—

The first time I noticed what I was losing,

I pretended that recovering it would be possible

whenever I needed to.

On occasion, my father sets up the machine,

flicks all the switches to the maximum,

turns off the living room lights,

and belts, slightly flat and out of sync,

to love songs, laments, boléros.

He hardly invites me to join in now,

not when he wants to boast about me,

not when the duet cues for a second voice,

not when he is alone.

I have my own theories why

but I have never gone to any lengths

to prove them right or wrong.

He does not know that I watch from afar, telling myself

I should do it, collapse onto the cushioned lounge beside him,

initiate some large small talk,

and just sing.

—Track 1 (Reprise)—

The final realisation came eventually.

I thought I had forgotten about the Arirang logo,

the faithful MIDI backing vocalist,

my audible, imaginary friend.

I thought I was above it all when, really,

I craved it.

My origin story began long before

those nights my father spent under the disco ball,

long before the immigrant I wished I had stood up for,

long before Mariah,

long before.

I demanded it to erupt from dormancy

and there it was.

The first track still spins in my periphery,

insists on a place in my memory;

the notes waver and diverge

but they somehow always return to the tonic, to do.

The first track is who and why I am today.

Those lines are in everything I teach,

the melodies surging through my veins,

my stiff kisses —

One day, when I’m all grown,

Hardly will I forget

The years you taught me

When I was a child.