rīvus is a multi-gallery experience that interrogates what it means to coexist with waterways in the 21st century, engaging with anti-colonial environmentalism; ancestral technologies; art as activist science; and the thirst to possess.

Viewers encounter a collection of artworks that critically engage with the core problems of our time — and come away with answers. This is not a performative collection of work, but one that makes tangible steps towards achieving its ideological goals through cutting edge technologies.

Artistic Director of the 23rd Sydney Biennale, José Roca, told Honi his vision for this year’s theme resembled “more the delta than the source” of the theme’s titular waterway: a branching out into diverse ideas from a single common thread.

This sentiment is strikingly evident in the offerings on show: living seawalls, algae-based bioplastics, kinetic art, wild soundscapes, scientific practices, living portraits and works based in indigenous knowledge systems — rīvus encapsulates the complexities of a world wrapped in water, navigating its social and environmental landscapes.

First Nations artists are at the forefront this year, and it is reassuring to see this curatorial focus continue after the 22nd Biennale ‘NIRIN’, which opened just days before Sydney was plunged into its first lockdown in 2020.

In contrast to the 21st Biennale’s theme of ‘Superposition’, rīvus is remarkably focused in scope. Every work has a clear thematic basis, interrogating our relationships with water and ecology while arguing for potential futures.

Honi was invited to attend an advance preview of the 23rd Biennale’s five key gallery locations and offered the chance to speak with participants, and engage with their works up close. The Curatorium, composed of José Roca, Paschal Daantos Berry, Anna Davis, Hannah Donnelly, and Talia Linz, accompanied the tour and discussed the surfeit of innovative works on display.

National Art School

The tempest which had been encircling Sydney for several days was upon us, blaring down on the roof of the National Art School in Darlinghurst (NAS), Biennale Creative Director José Roca remarked that “we are hearing the voice of nature right now”. Situating the thematics of rīvus, José explained that each gallery-space or location is centred around a different conceptual wetland; NAS engages with submerged histories in still, stagnant waters.

Pointing to the suitability of NAS as the first location of the Biennale, NAS Director Steven Alderton described the school as “a cultural hub for young people and future art leaders”.

A vital work exhibited at NAS was the Myall Creek Gathering Cloak. The cloak, which is hung at the space’s entrance, was made by the National Committee of the Friends of Myall Creek and Local First Nations Community. Crossing from one side of the work to the other, a coverage of possum furs on one side are uncovered to reveal an oft-buried colonial history. Curatorium member Hannah Donnelly explained the work as relating to the role of water “in conflict as colonial penetration roots.”

Compositionally, the cloak includes a depiction of the Myall Creek massacre at its centre, incorporating Gomeroi songlines, local flora and fauna, and individual stories of life since the massacre. Ngarrabul / Gamilaraay / Yuwaalaraay / Kooma artist Adele Chapman-Burgess explained the work includes the first imprint of non-Indigenous hands on a possum cloak – those of the Memorial Committee.

The theme of occupation and colonisation continued throughout the space. Notably, the works of Jumana Emil Abboud engage with the suppressed and forgotten traditions which surround the waterways of Occupied Palistinian Territories. Skillfully communicating a painful yearning for her homeland, Abboud’s artworks blend washes of acrylic and gouache to create almost apparition-like figures; the stories of her culture recalled only in foggy memories.

Mourning the loss of the deep-rooted cultural stories and teachings once shared between generations along riverbeds, and searching for continuity, Abboud said, “I demand for us to revisit the landscape. I demand for folktales to be told again, or for the return of our oral history”. Just as the occupation erases Palestinian sovereignty, women and children’s oral traditions of the land are erased.

Themes central to the Biennale, such as ‘eco-horror,’ animal ecology, and the natural impacts of colonial enterprise, are introduced in NAS through the works of Erin Coates. The dark, metallic graphite materiality of her sketches reflect the coexistence and transfer of heavy metals into the bones of dolphins in the Swan River. Coates explains that the collection displays “a dark speculation” about our present times and the impending future.

The opening themes of the exhibition are brought to fruition as they are introduced across the interwoven buildings of NAS — whetting audiences’ appetites for what is to come.

Art Gallery of NSW

The Biennale continued at the Art Gallery of NSW (AGNSW), in which avant-garde works acted as an intervention against the traditional gallery space. Roca specifically noted that the goal of many of these works is to link “art as metaphor and art as direct action”. A digital installation, One beat, one tree by the late Belgian artist Naziha Mestaoui, sits in the gallery’s foyer and invites audiences to plant a tree in a digital field – with each tree then going on to be planted in the physical world. This work reflects the Biennale’s wider concern with interaction and participation, holding a range of daily public programs planned over the course of its four-month duration.

Looming over the entryway of AGNSW, the grass-based portraits created by Heather Ackroyd and Dan Harvey command the attention of gallery-entrants. Ackroyd told Honi that their works, at over four metres tall, are “blowing up the intimacy of a portrait to an epic landscape”.

Working from seed, the duo created their works in Marrickville’s old reverse garbage building. Projecting the negative image of their subject in gradations of white light onto their effective ‘garden bed,’ or canvas, the seeds grow into blades of grass in varying shades of green. Speaking to their process, Ackroyd told Honi that “chlorophyll is a quasi-magical molecule” where it imprints subjects and designs onto the grass to a molecular level, using targeted photosynthesis. They will eventually fade and wither — reminiscent of the slow disappearance of ecosystems and animals in the wake of climate catastrophe.

The full-body living portraits depict the youth climate activist Lillie Madden and her uncle and Gadigal elder, Uncle Charles Madden. These subjects reflect the consistent political undercurrent of Ackroyd and Harvey’s artistic philosophy – one which is deeply environmentalist, radical and meaningful; strongly aligning with the thematics of the 23rd Biennale.

Additionally, as co-founders of the activist collective Culture Declares Emergency, Ackroyd and Harvey have spent over 30 years developing their art practice from germinating seeds to full-grown portraits.

These dynamic, innovative works are an undeniable stand-out of the Biennale which must be seen in the grassy flesh to be wholly appreciated.

The arguable centrepiece of the Biennale at AGNSW is an installation of John Kelly and Rena Shein’s Nyanghan nyinda me you — which showcases the first handmade tree canoe in decades. Situated in the recently renovated grand courts of the Gallery, which traditionally hold 15th-19th century European art, the positioning of this work signifies a cultural reclamation of the space. Utilising ancestral technologies and traditional First Nations techniques to create the canoe, Kelly quoted his father, saying, “be your own mentor, not your own tormentor.”

While introducing the work, Badger Bates, who is a Barkandji Elder, powerfully used the anatomy of his arms and torso to explain the anatomy of the Murray-Darling, or Barka, river system to which the work relates. Lamenting the damages caused to these river systems by colonisation and western industry, Bates implored observers to “tell the government to stop letting people rape our country”.

The interior of the canoe is filled with miniature clay birds nests created by the Kempsie community and children from the Dalaigur Preschool.

Museum of Contemporary Art

Deep time and psychological waters frame the works at The Museum of Contemporary Art (MCA), with the entire third floor of the venue taken over by the Biennale. Susanne Cotter, the newly appointed Director of the Museum, reflected on the Biennale’s use of ‘participants’ rather than ‘artists’ to describe contributors to the exhibition, who may also be thinkers, scientists, or even inanimate objects.

The oldest participant of the Biennale is the 365 million year old Canowindra fish fossil — displayed in public for the first time. Dating back to the Denovian geologic period, also known as ‘the age of the fishes,’ the fossilised fish were likely amongst the first generation of land-exploring aquatic animals.

Perhaps an odd choice for a Biennale of art, the fossil harkens viewers back to a time when oceans ruled the world, and the water was the place from which we came. Reflecting the motif of deep-time, aquatic ecologies, and humanism, it is an apt addition to rīvus which only reiterates the exhibition’s thematic throughlines carefully crafted by Roca.

The fossil operates as an artwork of the world, a tangible record of where we’ve been; a species derived from water.

Arguably the most interesting work at the MCA is A Connective Reveal — nagula by Robert Andrew, displayed across an entire wall. MCA curator Anna Davis explained that Andrew’s work sees two ‘palimpsest machines’ (modified 3D printers) slowly move across the walls in a carefully choreographed pre-programmed dance.

The machines are in a constant process of erasure and inscription, using high-pressure water jets to displace the work’s chalk layer and allow the ochre beneath to bleed down the wall. The work will evolve over the course of months, eventually revealing words in Andrew’s own Yawuru language written in the deep red ochre that has been mechanically excavated.

Walsh Bay Arts District

Suspended over the waters of Sydney Harbour, Pier 2/3 at the Walsh Bay Arts District feels fully integrated both into the theme of rīvus as well as Sydney’s art scene at large. This is no small feat for the newly-renovated district, with the Biennale being the first public event on the pier since a $371 million investment from the NSW government.

The pier makes a fitting backdrop for the displayed works, with views of the water below and the Harbour Bridge framing the venue’s thematic basis of saltwater and its interactions with freshwater. Installation works dominate, transforming the space into one so wholly-encompassing as to rival the Venice Biennale.

The most striking work of the pier is situated at the far end, by Melissa Dubbin and Aaron Davison; the near-alchemical construction of the work reflects our origins as water-based beings in embryonic fluids. Entitled Delay Lines, the work is built from laboratory-like glassware and materials that remind viewers of a scientific space. Linking back to rīvus’ integral theme of art as science, the integrated products of these two fields are indicative of the emerging ingenuity of our modern times as we navigate the climate crisis with new technologies, ideas, and pathways.

The “invisible energies of water” are observed in the work’s closed-system environment: heated by the internal computer itself, the water twists and transforms through the rigged glass tubing. Glistening as it shifts into a condensed form, the water mirrors our own transformation as a species — snared in a constant process of adapting and shifting into new iterations of ourselves.

The space was also home to installation works from the Torres Strait 8 – a group of Zenadh Kes traditional owners who took the Australian Government to the UN for failing to adequately address climate change. True to their experience, NSW’s recent record-breaking floods meant that one of their works, a number of totemic poles, failed to arrive at the Biennale in time for our viewing.

Yessie Mosby, a member of the 8, told us about his culture and his experience of the ocean: “We are saltwater people. We go to bed listening to sea waves, we wake up listening to sea waves”. He elaborated that “[the ocean] is our maternity ward, our hospital, our library”.

Their work was accompanied by a number of prints and drawings related to the Torres Strait 8’s ‘Our Islands Our Home’ campaign, a meaningful addition to the collection that drove home the immediacy of climate change’s impacts for First Nations people.

Barangaroo

The Cutaway at Barangaroo is a space that many students have likely not yet visited. The Barangaroo precinct is an often prohibitively-expensive area dominated by upscale restaurants, bars, and office buildings. The Biennale, however, is a free exhibition that makes a visit well worthwhile.

rīvus makes great use of the Cutaway’s towering heights, with a large-scale bamboo installation by Cave Urban hanging from the ceiling as a through-line uniting the cavernous space. Exposed to the elements, during our own viewing a pair of birds darted about while pouring rain cascaded through the open air side of the venue — appropriate for a Biennale so concerned with water and ecology.

The curators at this venue spoke to the “cosmic and terrestrial forces” at work within the space. Acting as something of a conclusion to the exhibition as a whole, the works in this space traversed the wide spectrum of themes which the Biennale sought to tackle.

A highlight in this vein was created by Jessie French, an algae-based artist who blends scientific and artistic knowledge to create new biodegradable ‘leathers’, materials, and plastics. Functioning as an installation work, French’s laboratory in The Cutaway blurred the lines between art and science; green liquid algae bubbled away on her stovetop as she told Honi, stick-blender in hand, that her work encompasses a “new generation of plastic”.

She explained to us that her bioplastics, made from algae found in waterways, are “thermo-resettable” — meaning they can be melted back into a liquid and reformed into a new solid, repeatedly. Using non-toxic pigments and polymers derived from red microalgae, French also creates large hanging sheets of semi-translucent plastic leathers in a variety of hues and shades, blooming with organic forms of colour.

Her work directly considers how scientific knowledge systems can be linked to artistic practices in environmentally meaningful ways: a concept central to the goals of rīvus. Producing a viable alternative to petrochemical plastics, French also creates plates, cups and other daily objects out of her custom-brewed bioplastic.

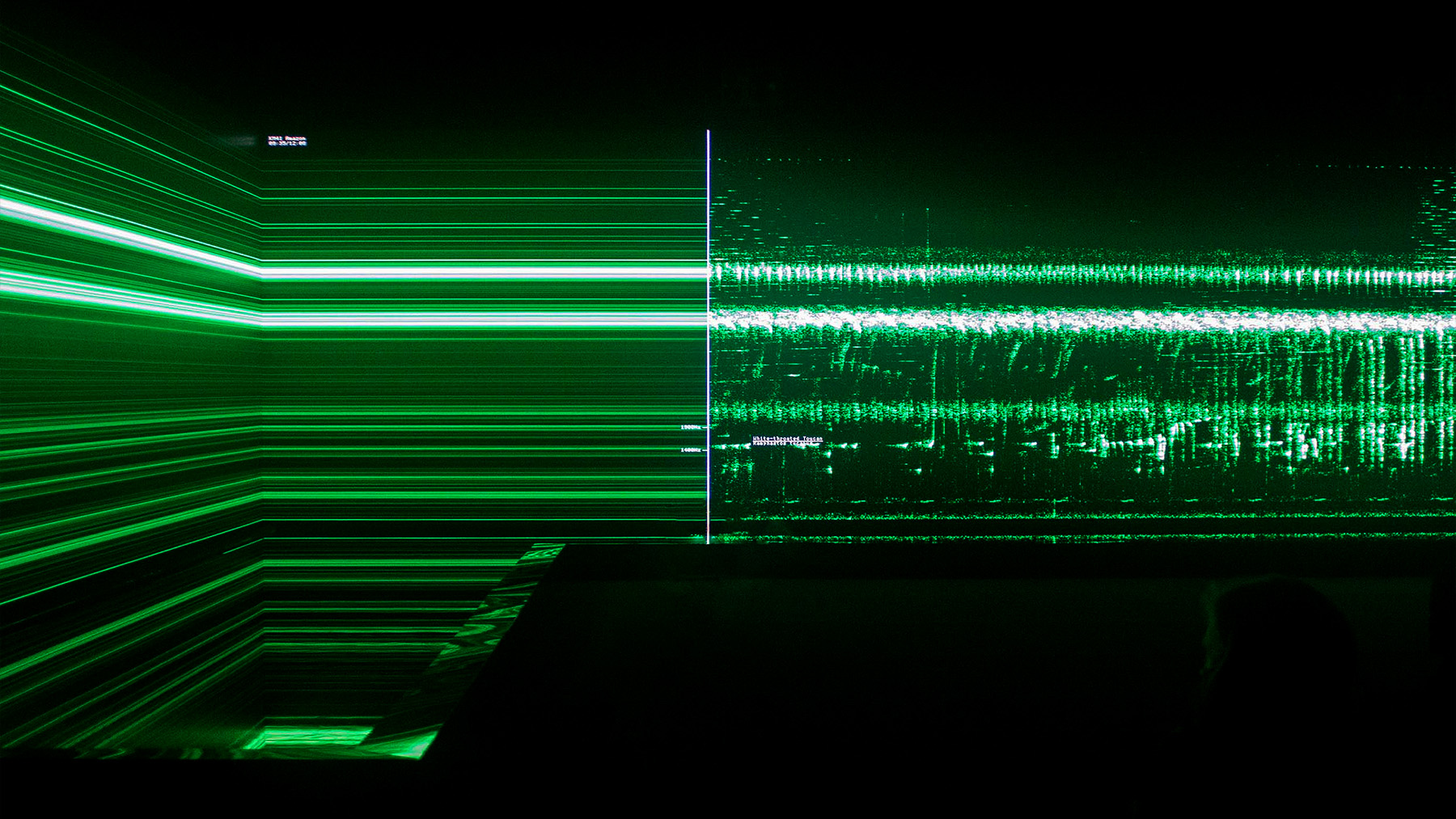

Located two floors above the Cutaway on the Stargazer lawn, the Great Animal Orchestra is a must-see work of the Biennale. Developed by American soundscape ecologist Bernie Krause in collaboration with art collective United Visual Artists, the work is primarily audio based — Krause notes that sound is usually an afterthought in art and film, the last element to be added. The Great Animal Orchestra comprises audio recordings of nature taken from vulnerable habitats in Africa, North America, the Pacific Ocean and the Amazon River. Krause refers to the knowledge to be gleaned from these sounds as “a critical database” comparable to the Library of Alexandria, and hopes that when people hear this plea they will come away changed.

Sitting in a darkened room listening to the sounds of endangered birds from continents away, Krause’s words ring true. Waveforms of animal calls and ocean waves scroll across darkened screens, reflected in waters below. The core of this work is to listen, as well as act, before the sounds of the Orchestra are permanently silenced.

rīvus is everything art lovers have been asking for — socially conscious and sustainable in theme and execution, it succeeds in operating on a grand scale without sacrificing the nuance of its concept.

The 23rd Biennale of Sydney is open now until June 13 at the above locations as well as Arts and Cultural Exchange in Parramatta.