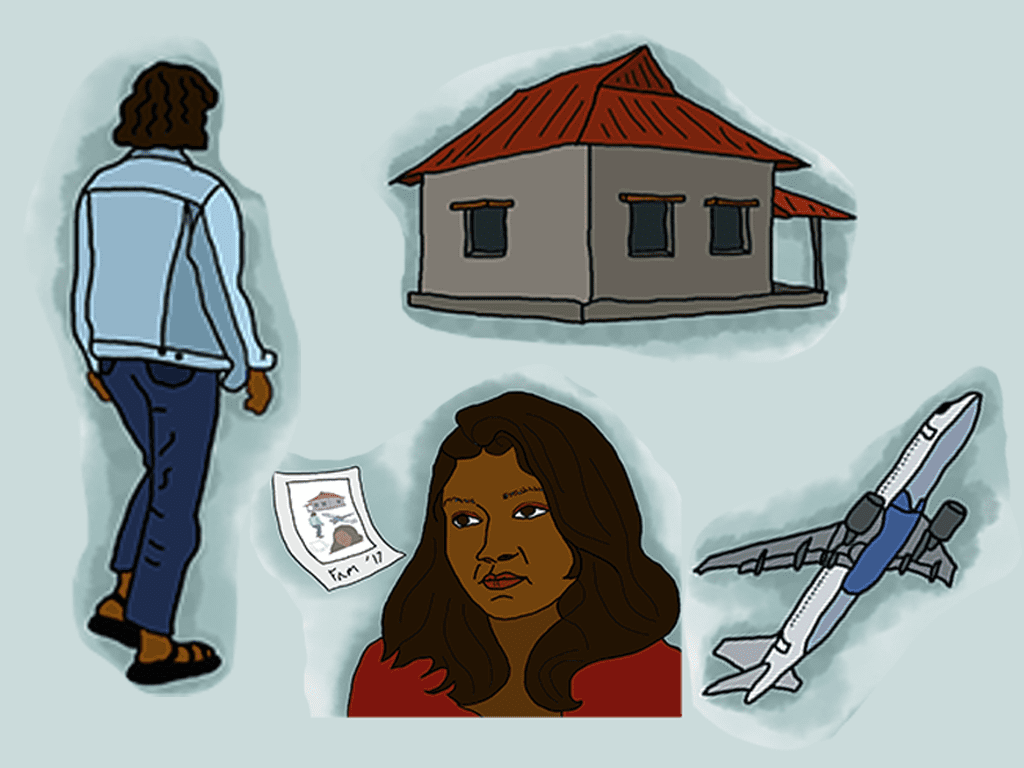

It’s funny how quickly we can become strangers to our own homes. Only a couple of weeks ago I flew over the Indian Ocean and landed in a makeshift bedroom in Bangladesh, anticipating that the foreign territory of my grandparents’ house would be difficult to adjust to. But the days spent in my homeland, surrounded by the warmth of family, drifted by smoothly, and it was only when it came time to return that an acute sense of discomfort pervaded me. I tried to suppress the feeling until I unlocked my bedroom door again in Sydney.

That’s when the dreary homesickness settled in.

It was a disease of the heart, a pressingly painful feeling of loneliness that made me feel like nothing was right. I lost my appetite for cereal in the mornings. I hated the sound of Australian news on TV. I spent hours sifting through the same old pictures of my trip, wondering if and when I’d be able to return. But the worst part was the nagging guilt – the feeling that my homesickness was in no way justified. Sydney was my home, and had been for as long as I could remember. How can someone feel homesick at home? After all, my family and I were migrants — we chose to come across the seas and grow our roots in Sydney. Did my homesickness indicate an ingratitude for my present life, and for the home that my parents had worked so hard to establish?

In my frenzy to treat the lingering discomfort, I stumbled upon an interesting term – ‘imagined return’, coined by Prof. Javier Serrano of University of California in his 2008 article, ‘The Imagined Return: Hope and Imagination among International Migrants from Rural Mexico’. Serrano suggests that while migrants are drawn overseas in the promise of a more prosperous tomorrow, they often idealise a valiant return to their homeland as a kind of reckoning with the past that they left behind. Serrano states that for migrants, the prospect of ultimately returning to the comforts of the homeland is often what gives them the confidence to leave the nest in the first place.

The imagined return I had conjured linked back to my own family heritage, and the ancestral trend of migration sewn into Bangladeshi history. The exodus of migrants from rural areas to urban cities has been long-standing, fuelled by prospects of finding work, treatment, or better educational opportunities in the developed city.

In fact, the enduring mobility in the Bengal region has links to the history of migration in greater South Asia, dating back to the partition period of the colonial era, when India was divided into Pakistan, and eventually Bangladesh. Even today, like an unspoken code, one of the things a first-generation Bengali migrant asks another is “Where’s your desher bari?”, or ‘village home’. It’s a link back to a time before migration was so common.

My grandparents always told us about the simple charm of their desher baris, the swinging palm trees, the tin-roofed houses, the local ponds where they learnt to swim. These stories almost always contained a nostalgic flair; a longing for a simpler life, like the telling and retelling of these stories was a kind of coping mechanism for chronic homesickness, a means to imagine a return to what once was.

I’m lucky to say that time eventually healed my wounds, and the tormenting feelings of isolation and disorientation passed. As my body recalibrated to the flows of regularity, my home away from home drifted to a memory as it was always destined to, and the fantasy of an alternate life, an imagined return to the homeland, became clear for what it was – simply a figment of the imagination.