Lecturers explaining Orientalism should simply take their students on a field trip to Uncle Ming’s Bar — a grotesque hodgepodge of fetishised Asian cultures mashed together by owners who probably don’t know how to use chopsticks.

Ming’s is situated on York Street across the road from Wynyard Park, down a semi-concealed staircase below an unassuming tailor. Since its opening in 2012, Ming’s has faithfully served Sydneysiders with its ambient atmosphere, creative cocktails, and in-your-face racial insensitivity.

Yet upon arrival, you may at first be oblivious to the cultural bastardisation that lies before you. As the child of a first-generation Chinese immigrant, I am somewhat ashamed to admit that I was initially entranced by the soft red glow that bathes the venue, and lured — as if by magnetism — to the attractively backlit bar primed to dull critical thinking.

Thankfully, once the alcohol wore off, the scarlet-tinged oasis that lay before me eventually faded. What remains — after closer inspection and a bit of online sleuthing — is a genuine case for why Ming’s exemplifies contemporary Orientalism.

At risk of oversimplification, Edward Said defined Orientalism as the Western tradition of perceiving the East as ‘exotic’, undeveloped and inferior in a way that enables a presumption of authority. In the case of Ming’s, Orientalism manifests clearly in four key departments.

1. Exoticism

The bar is branded as an “opium-den” run by the fictional Uncle Ming: one of “Shanghai’s most notorious figures – a sweet potato vendor who began a life of crime as a policeman collecting protection money from local opium traders”. If a team of writers were locked in a room with only Pauline Hanson interviews and Rush Hour gag reels playing on repeat, I doubt they could conjure up more offensive clichés for the branding of a Chinese-themed establishment.

Putting aside the fact that associating China with opium is such a vacuous stereotype, describing a social destination as an opium den is utterly morbid. Opium — a source of morphine and heroin — caused widespread addiction in China from the 18th Century. Funnily enough, it was Western countries that imported the drug into Chinese territory, against the wishes and laws of the Qing Dynasty. The problem became so severe that China fought two wars against Britain and Britain-France in an attempt, in part, to stop imports of the drug.

In this context, opium symbolises a rather tragic segment of Chinese history. On top of that, a Google search of ‘opium den’ produces images of dingy, crowded rooms filled with forlorn and emaciated figures — the sight of which would likely terrify the ignorant halfwit who first dreamt up the bar’s concept.

Beyond being distasteful, such stereotypes perpetuate an alienating form of exoticism. For the sake of branding, Ming’s operators have created a caricature that subliminally distances China and its people from the Western hegemon. Consequently, Chinese people are depicted not as part of the community but as ‘the Other’; not as the everyday patrons of Ming’s but as “sweet potato vendors”, opium-users, or “notorious” criminals in Shanghai.

2. Homogenisation

Westerners conflating disparate Asian nationalities and reducing Asia to a single homogenous entity is a common occurrence. Once, an undiscerning drunk fellow yelled out “ninja samurai” to my Chinese friend and I as we walked down a quiet street in Western Sydney. Ming’s elevates such callous homogenisation to dizzyingly insensitive heights.

Across the internet, Ming’s is branded as either Asian-themed or Chinese-themed. It’s patently obvious that, to the owners, there is no real difference.

Ming’s fictional backstory and the etymology of his name point to a Chinese influence. Upon entry to the bar however, this becomes enmeshed in a careless concoction of elements from vastly different East Asian countries. Singapore, Japan, Malaysia, South Korea, North Korea and Vietnam all contribute to Ming’s branding, menus and interior design.

Aside from reinforcing the reductive Western perception of Asia as one homogenised entity, the grotesque cultural Frankenstein that is Uncle Ming’s provides a clear insight into the racist worldview of its management.

This is particularly apparent in the bar’s egregious marketing, with their Instagram feed doubling as a public noticeboard for the account owner’s racist musings. The profile is littered with photos from various Asian cultures with captions belittling its subjects in attempts to comedically promote the bar. One is captioned “Throwback to that one time Uncle Ming won the Melbourne cup” and depicts a Japanese Samurai Warrior on a silk painting. Yep, a Japanese Samurai Warrior. Other posts identify Uncle Ming in photos of a real-life Chinese street vendor and Japanese salaryman.

At Uncle Ming’s Bar, Asia is one monolithic entity that warrants no meaningful exploration, respect or celebration. Rather, its nations and people are to be stereotyped, ridiculed and exploited for profit.

3. Racist impersonations

The bar frequently adopts the online persona of Uncle Ming, which involves typing in broken English and speaking about Ming in the third person. One post, depicting a random man bending over on a sidewalk is captioned “Uncle Ming has menu on his website so you don’t have to bend over and squint like cousin Chan … Uncle Ming has forgot that time you drew in crayon on auntie Fung’s wall and blamed it on Uncle Ming.”

Another post is captioned “Mumma Ming very angry with Uncle Ming. He forget Mothers Day. 16 voicemails. Uncle Ming must wait till afternoon, to drink and listen to the many time he dishonour Mumma Ming.”

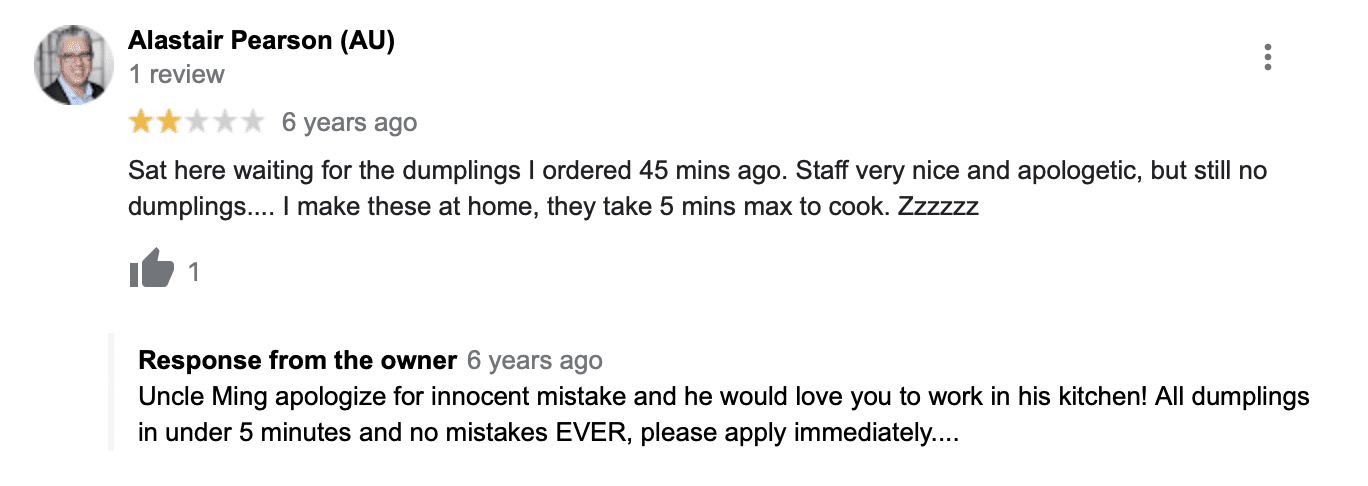

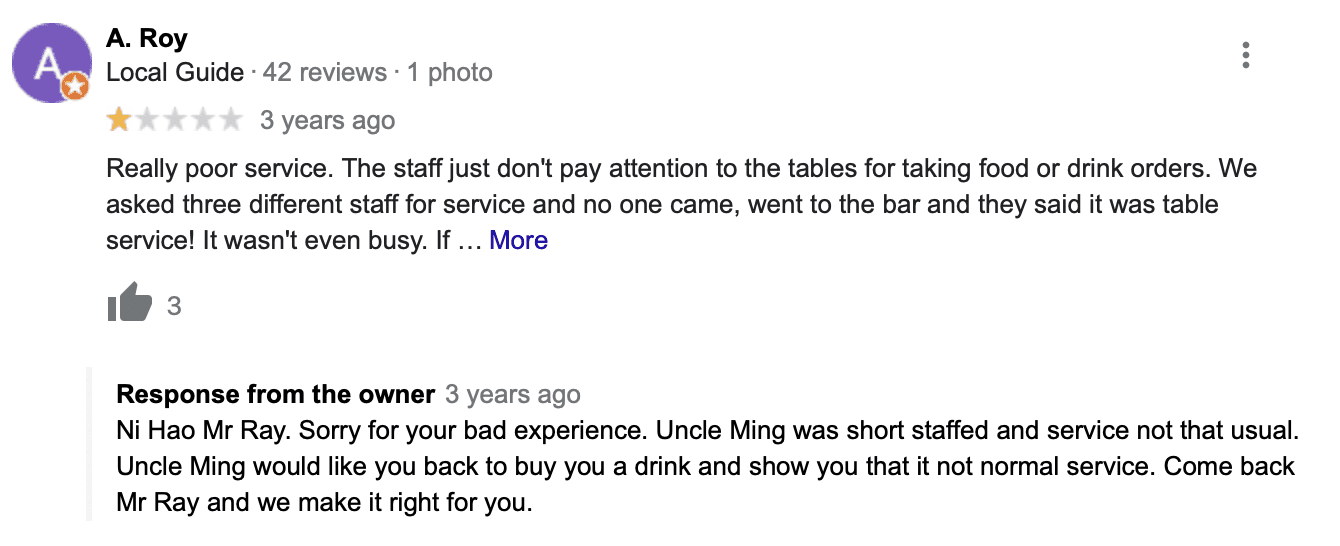

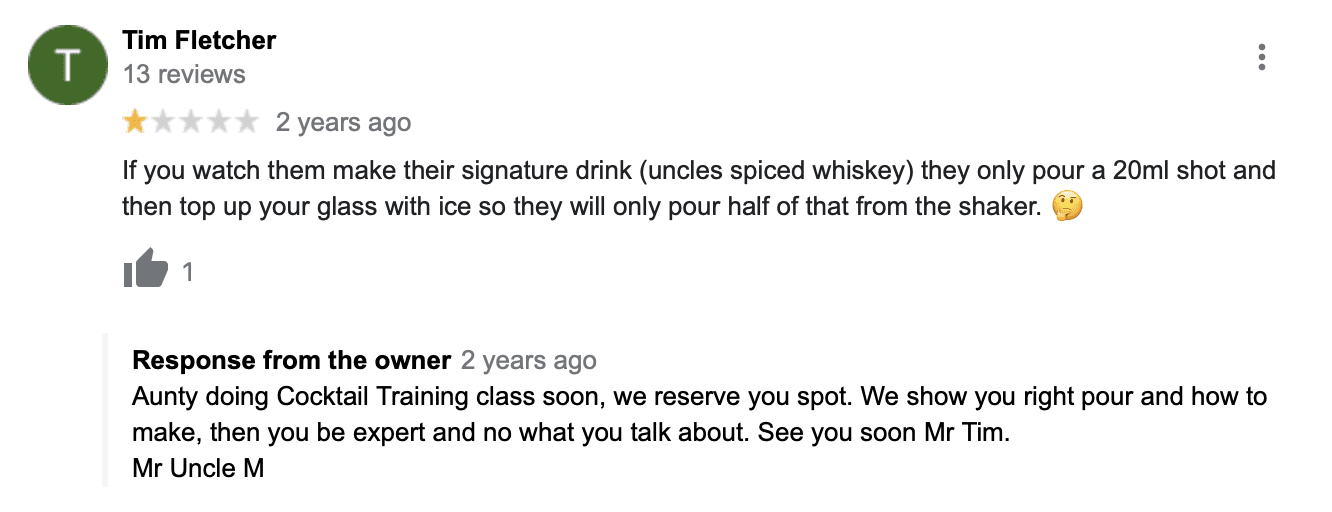

The Ming persona is also adopted in their responses to Google reviews. One reads “Ni Hao Mr Saagar, when Ming busy we cannot break rules and the wait only 3-7 mins. Ming think you say sorry to your wife for being an hour late and don’t argue with guard. Aunty Ming don’t like to wait for 1 hour and Ming always sorry to Aunty.”

If you’re feeling masochistic and want to survey the full extent of the bar’s racism, peruse their Instagram and responses to Google reviews.

4. White, white, white

Unsurprisingly, photographic evidence suggests Ming’s patronage is largely white, or failing that, largely stupid. While some Asian-looking revellers have publicly tagged the bar in social media posts, it’s worth noting that the capacity of these individuals to critique the venue was likely either inhibited by alcohol or their possession of fewer brain cells than Instagram followers.

Like the majority of its patrons, the managing director and co-founder of Uncle Ming’s Bar is the very white-looking Justin Best. While I allege no malice on Best’s part, the man’s entrepreneurialism demonstrates a startling lack of cultural sensitivity. Best(ie), if you’re reading this, try having a conversation with someone of Chinese descent. If that fails, maybe open up a map of Asia and look at the boundary lines – you gotta start somewhere.

~~~

If, after reading this article, you want the Uncle Ming’s experience without having to support a racist enterprise, try glueing a dried block of instant noodles to a wall and running into it headfirst. Culturally and physiologically speaking, that should have a comparable impact.

If, rather, you’d like to acquaint yourself with the theory of Orientalism, check out Edward Said. Maybe if Best had the fortune of coming across Said’s writing, he would not have opened a bar that’s very essence bastardises and exploits cultures that are not his own. Perhaps, in an alternative universe where he studied Arts instead of Commerce, Justin Best manages a tasteful CBD bar called Uncle Steve’s.