In Following the Equator: A Journey Around the World by Mark Twain, he famously proclaims that “truth is stranger than fiction, but it is because fiction is obliged to stick to possibilities; truth isn’t.” It doesn’t seem true that we could be living through a global pandemic and an extreme climate crisis manifesting itself in fires and floods, under a right-wing government, within a university that runs itself like a corporation. But here we are!

Many people cite escapism as the primary reason for why they read or involve themselves in any form of fictional storytelling. I’m the occasional fan of a well-crafted UpLit (think Eleanor Oliphant Is Completely Fine by Gail Honeyman) or a hero’s journey-esque story, but these kinds of books mostly feel unsatisfying. While I don’t propose we abolish the happy ending, at the moment they just leave me despondent in the face of our comparatively dystopian reality. Instead, absurdist fiction has become cathartic to me in that it forces the reader to acknowledge their lack of control and make a home within the chaos. It certainly doesn’t champion a ‘do-nothing’ response — in fact almost all absurdist fiction is inherently political — but it makes the weird and uncertain more palatable and therefore easier to respond to, or at least weather.

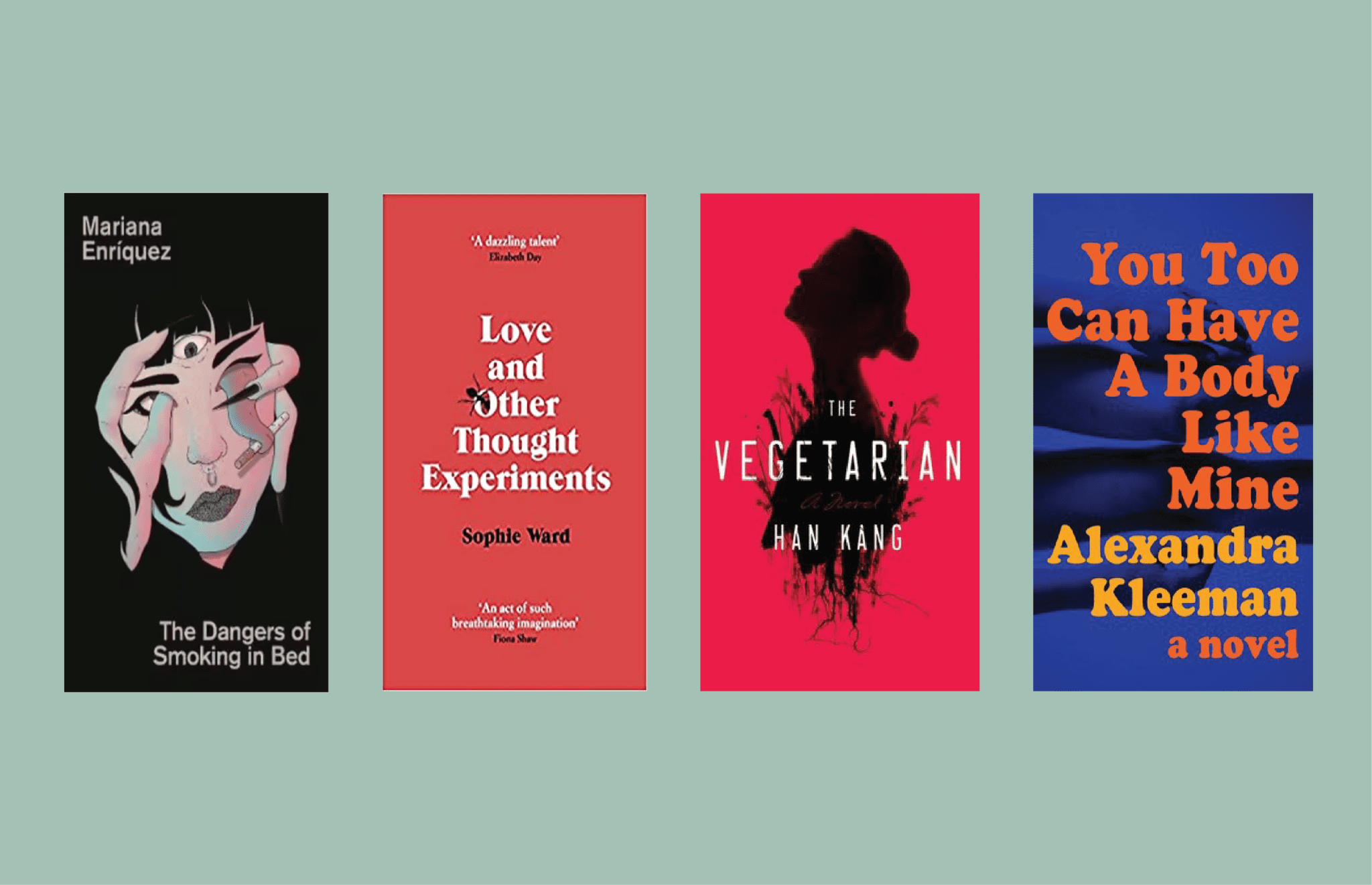

Over the past couple of years, I’ve indulged in female-written absurdist fiction to help make sense of our times. What I’ve found is completely nonsensical, and it’s beautiful. An all-time favourite is Han Kang’s The Vegetarian (2007), that left me in a spell that I still haven’t snapped out of (and I read it two years ago). Translated from Korean, we follow Yeong-hye as she seeks a more ‘plant-like’ existence as prompted by grotesque recurring nightmares of slaughter. Rebelling against traditional South Korean culture, she adopts a vegetarian lifestyle to passively protest her role as an uninspired but dutiful wife. We read perspectives from Yeong-hye’s husband, sister, and brother in-law, as their lives become increasingly entangled with Yeong-hye’s increasingly-extreme fantasies of abandoning her fleshly prison. As one of the most beautifully written books I’ve ever encountered, it is feminist absurdism at its finest.

I’m attracted to these pieces of feminist absurdism because the very nature of being female in our patriarchal world is absurd: navigating paradoxes, inhabiting worlds that tell us we can do anything but no, not like that. Following in this tradition, one of the only short story collections that kept me wanting more, The Dangers of Smoking in Bed by Mariana Enriquez, was first published in Spanish in 2009. It is scary, yes, but mostly in the way Enriquez personifies abstractions like teenage hysteria into dynamic narrative forces. She explores the codes of conduct that mediate public space, the interactions between witchcraft and wellness, and romance in the digital age. These discussions are led by tropes of missing people, cannibalism, abandoned homes, ghosts, and more, but always under the guiding light of feminist horror; her stories are unafraid to interrogate and extrapolate the fears women face on a daily basis. TDOSIB is intrinsically absurdist as nothing ever quite adds up, but its fierceness and cleverness means the reader never craves simplicity or resolution.

Similarly, in You Too Can Have a Body Like Mine (2015), Alexandra Kleeman, describing a chemist, writes that “it all smelled like beauty products, that anonymous female scent that we rub onto ourselves to blend into a wet, aggregate femininity, to smell like a person but not like any person in particular”. Who is this anonymous person? Kleeman refuses to answer. Characters are unnamed, except for A, B and C. Despite beginning as a rather tame tale of being fed up with one’s roommate and dead-end job, A soon transgresses into the outlandish world of cults and consumerism. The book is plagued by adverts for Kandy Kakes, an entirely synthetic sweet snack, and includes bizarre tales of Disappearing Dad Disorder, as well as a surreal reality show named ‘That’s My Partner!’. Completely baffling yet seductive, YTCHABLM follows Kleeman down a rabbit hole that left me disorientated and wanting more, and is perfect for lovers of the dystopian sci-fi television show Black Mirror.

Finally, Sophie Ward’s Love and Other Thought Experiments is a brilliantly executed piece of world-hopping, philosophical absurdist fiction. We begin with Rachel and Eliza: a couple who are trying for a baby. One night, Rachel wakes up and tells Eliza that an ant has crawled into her eye. Eliza does not believe her. From there, the reader is transported absolutely everywhere; inside Rachel’s brain, into the ant, into the future, into code, and then back to the beginning. Memorably, Ward claims that “we are not a brain… We are the purest distillation of consciousness without any of the distractions.” This thought seems to align with the novel itself and much absurdist fiction; wherein so much of what we fail to recognise in the everyday is distilled and given a new and profound attention.

As Camus famously professed, “the realisation that life is absurd cannot be an end, but only a beginning”. Similarly, the realisation that our world contains thousands of microcosms of absurdity bound neatly on white pages is a beginning, and the possibilities these offer us is why I doubt my love for this genre will ever end.