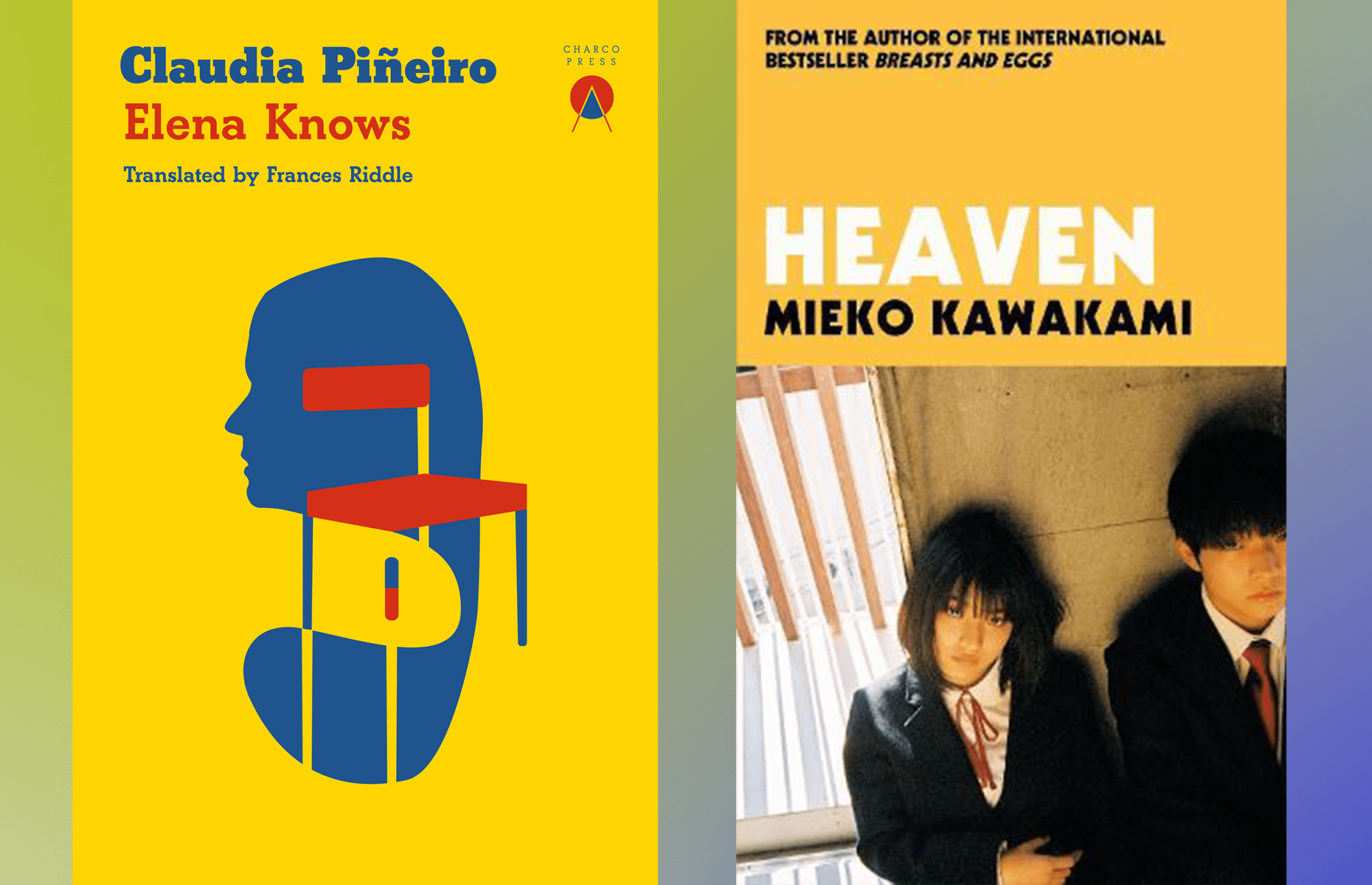

Recently, I have had the pleasure of reading two novels that were selected for the International Booker Prize shortlist: Heaven by Mieko Kawakami and Elena Knows by Claudia Piñeiro. Established in 2005, the International Booker Prize selects novels that have been translated into English to showcase some of the most engaging original literature emerging outside of the English-speaking world. Amidst an intriguing shortlist — The Books of Jacob by Olga Tokarczuk, Tomb of Sand by Geetanjali Shree, A New Name: Septology VI-VII by Jon Fosse, and Cursed Bunny by Bora Chung — I have relished reading Kawakami and Piñeiro’s pieces. The prize seeks to exemplify the power of translation as a literary form and a practice.

Heaven centres on two characters — a narrator who is only referred to as ‘Eyes’ because of his lazy eye, and Kojima. Both are students at the same school in Japan in the early 1990s, and Kawakami explores how their experiences of violent bullying simultaneously unite them together and draw them apart. The novel blends philosophical conversations — particularly those drawing on existential nihilism and Friedrich Nietzsche’s Thus Spoke Zarathustra — to ground its representation of bullying as a discursive site where ethics, identity, friendship, and existence can be discussed. Initially, Eyes and Kojima begin to forge a friendship over their shared experience of bullying. However, as the novel progresses and they become more aware of their own objectification, they grow apart, finding it difficult to understand each other’s sense of why they are bullied. Kawakami delivers the story in a clear, nonchalant, and graphic style — her language can be seen oscillating between the violence that Eyes is subjected to by classmates Ninomiya and Momose, to expressionistic observations of Japanese landscape, art, and suburban life. Heaven is emotionally challenging but occasionally loses its nuance because of the sometimes straightforward ways it engages with universal and much-asked philosophical questions.

These problems — though somewhat minor — that I had with Heaven also appeared in Piñeiro’s novel but, fortunately, these were its strengths. Like Heaven, Elena Knows is a highly emotional, complex, and rich story that centres on Elena, a woman diagnosed with Parkinson’s Disease, who attempts to uncover why her daughter Rita was found hanging off the church belfry on one stormy day in Argentina.

Whilst the novel is short, it packs a punch: referring to Parkinson’s in an anthropomorphic mode as ‘Herself’, referring to the new version of Elena that has taken over and consumed her body, Piñeiro’s language echoes the ways that Parkinson’s manifests in her body. Elena’s sentences are methodical, sharp, and her diction equally so. She is convinced that Rita did not commit suicide: the novel reveals Rita’s fear of thunderstorms as being a fundamental aspect of her character. However, Elena’s sense of certainty is flawed, and curbs her ability to accept that knowledge is a porous, ever-changing and adaptable phenomena that she cannot fully grasp. Following a shifting timeline straddling the day of Rita’s death and Elena’s present, Piñeiro manages to engage in complex discussions around the microaggressions that disabled people face, and how institutions like the Catholic Church can complicate how one reconciles life, death, belief in God, and faith.

If I had to pick a winner between these two, Elena Knows comes out on top. It left me sad, emotional, but hopeful that the novel form can still be tested, challenged, and meaningfully contribute to important, and at times controversial, conversations. But, I will be reading more of Kawakami’s work — Breasts and Eggs, and the forthcoming, All the Lovers in the Night.