Students and NSW health sector workers gathered at the Susan Wakil building for the Nursing Power forum on Wednesday to discuss public health and nursing workplace challenges.

The forum was dominated by criticism of the state of healthcare in Western Sydney. All panel members agreed that healthcare needs of Western Sydney communities are not being met.

Eliza Wright, a mental health nurse from Western Sydney, stated that chronic health issues in Western Sydney get “swept under the rug.”

She later revealed that “in Western Sydney, there’s 10 beds” belonging to a “high-dependency” unit – a type of in-patient, mental-health ward that provides increased levels of intervention. Such conditions, according to Wright, are not enough given the “high socio-economic disparity” in Western Sydney which is tied to increased risk of mental health problems.

Wright also observed that doctors coming from “privileged backgrounds” working in Western Sydney hospitals “don’t tend to respect [these] patients”.

Helen Dick, a former nurse educator and registered nurse, also highlighted a “lack of homegrown doctors” being an issue within many lower socioeconomic areas, with an audience member identifying that this was a symptom of “inequity within education”.

Dick also said that one of the biggest issues they’ve faced is determining whether patients from the area can afford the best treatment.

The panel members also believed that there are more effective ways the state government can invest and improve healthcare services.

NSW Nurses and Midwives Association (NSWNMA) representative Michael Whaites, criticised the government for failing to address the structural issues facing hospitals despite promises to provide material assistance.

“The number one issue is the ratios question,” Whaites said, in reference to the smaller nurse-to-patient ratio of 1:4 (one nurse to four patients).

Whilst Wright stated that many new facilities are being built, they are not tailored to the needs of health practitioners and patients, and often go unused as there are not enough nurses to supervise their use by patients. “[It’s] a bandaid solution.”

“We’ve got a 30 bed ward…with four nurses on night shift…you have two patients that need one-to-one nursing and you’re kinda just effed,” Wright said, on the need for better staffing ratios.

Dick noted thes stark contrast to Victoria, who have had ratios since 2015.

“In Victoria… there were always experienced nurses who ran the shift and could support younger nurses… It wasn’t a nurse fresh out of uni making [major] decisions,” they said.

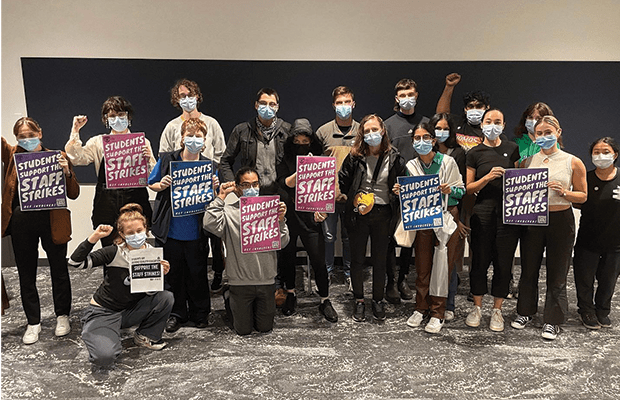

Nurses and midwives have been on strike twice this year, rallying for better staffing ratios, safer working conditions and wage increases.

Attendees also expressed concern over the lack of training and support that assistant nurses receive from hospitals and universities.

Wright observed that there were often not enough registered nurses to teach students or newly graduated nurses at their hospital: “The poor educator tries to find at least one RN [registered nurse] so it’s legal.”

A student also shared how a peer sustained a back injury whilst on a nursing placement, and is now unable to stand upright for more than two hours. The student mentioned that their peer did not receive any financial compensation from the University and is essentially being “kicked out” of their degree as they could no longer complete their placements.

Wright and Whaites both cautioned against underestimating the toll that nursing can have on mental-health and encouraged building strong social support networks.

Dick also revealed that in nursing, there’s the expectation from the government and within workplace culture to overwork yourself out of “goodwill”.

Whaites emphasises that students should know that they have the “right to say no” and the “only way” we can see improvements in the health system and education, is if students become comfortable with “using [their] voices.”