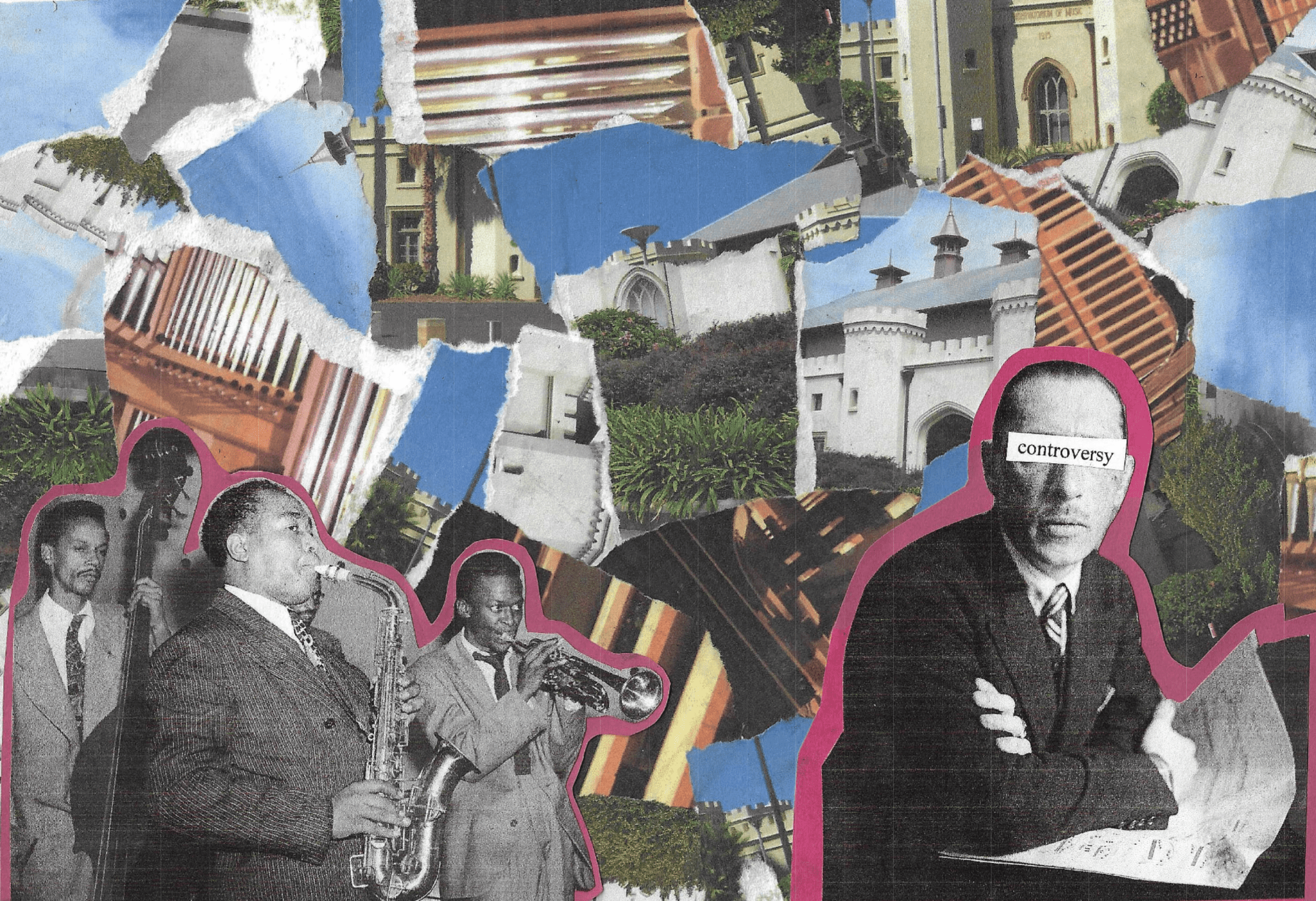

Art may be considered one of the most controversial aspects of culture. It only seems suitable that the institution responsible for creating some of the most renowned musicians and artists in this country would also have a few controversies of its own. Ever since it was founded in 1915, the Conservatorium has been in the public spotlight many a time, for better or for worse.

To start, we should return to the very origins of the Con. Even before it was founded, the circumstances surrounding its founding were quite unique. The universities of Adelaide and Melbourne had established a Conservatorium: in 1900 and 1913 respectively. These Conservatoria were based on the ideals of the English system, focusing on the academia and analysis of music rather than performance.

The University of Sydney was quite slow to follow suit, instead believing in 1909 that “the subject [of music] was only useful as an academic ornament and its cost would therefore have to be met by private philanthropy”. Despite several alumni bequeathing large sums of money for the purpose of musical education, it was not until 1940 that USyd founded the Department of Music. Arguably, these attitudes have continued 113 years later, with the historically hard-earned prestige of the Con often used as a marketing gimmick by the University now that it falls under its jurisdiction, rather than funding and supporting its work equally to other faculties.

Because of this insistence of “no music”, the Conservatorium wasn’t always part of the University. Originally called the NSW State Conservatorium of Music, the Con was founded by the Labor Party, spearheaded by Campbell Carmichael, the Minister for Public Instruction from 1911 to 1915. The Con was a pet project for him, founding a Committee without debate to find a location to host the building and its director. Prominent early-twentieth century composers Camille Saint-Saëns and Edward Elgar were both asked to join the director-appointment committee, but declined. Carmichael promptly ignored every recommendation given to him. The search for directors looked all over the world (as long as they weren’t German), with letters of recommendation coming from renowned composers such as Tchaikovsky and Stravinsky, until Belgian violinist Henri Verbrugghen was finally appointed.

The Con was funded and run by the State Education Department, with funding promptly cut as soon as the new Liberal/National government came into power in 1916. After many years running the only professional orchestra in the country alongside the Con, and an utter refusal to increase his salary, Verbrugghen left for the Minnesota Symphony Orchestra.

Potential sites for the building included refurbishing Paddy’s Markets, a location that, personally, I am glad was left as an alternative. Not only was it cheaper to build at its current site in the Royal Botanical Gardens in Sydney, it also has one of the most incredible views of any university campus in the world. The building hosting the Con was originally the new stables commissioned by Governor Macquarie in a direct contravention of a firm order from the Colonial Office, and began construction in 1817. Designed by colonial architect Francis Greenway, they were so marvellously lavish that, in a report back to London, the English Judge Commissioner John Briggs was aghast at the “useless magnificence”, ultimately leading to Macquarie’s offer of resignation in 1820.

This is only the beginning of the story of the Con and its colourful history. In its 107 years of teaching, many of its directors have been thrust into the limelight. Its second (if not most) influential director, Dr Eugene Goossens, was forced to leave the Con in 1956 after a scandal arising from the public’s discovery of his relations to occultist Rosaleen Norton. The self-proclaimed witch and artist better known as “the Witch of Kings Cross” had many items and interests considered pornographic and occult, a hobby Goossens controversially shared.

Much more recently, Professor Kim Walker brought legal proceedings against the University of Sydney for defamation against her reputation. It was alleged in the press that Walker had plagiarised content in lectures given to the Art Gallery of NSW. The immediate previous Dean, Professor Karl Kramer was also asked to resign in 2015 after his expenditure of $5000 of University money came under investigation. It was revealed that $1000 went to a supposedly lavish staff dinner, to which one of the listed attendees commented about the proceedings of the night, “I wasn’t even in the country”.

There are so many controversies in the Con’s history that the Sydney Morning Herald deems it worthy to have an entire timeline dedicated to documenting them. Surely, going into the future, we can expect the Con and its inhabitants to produce even more outrageous stories to hear.