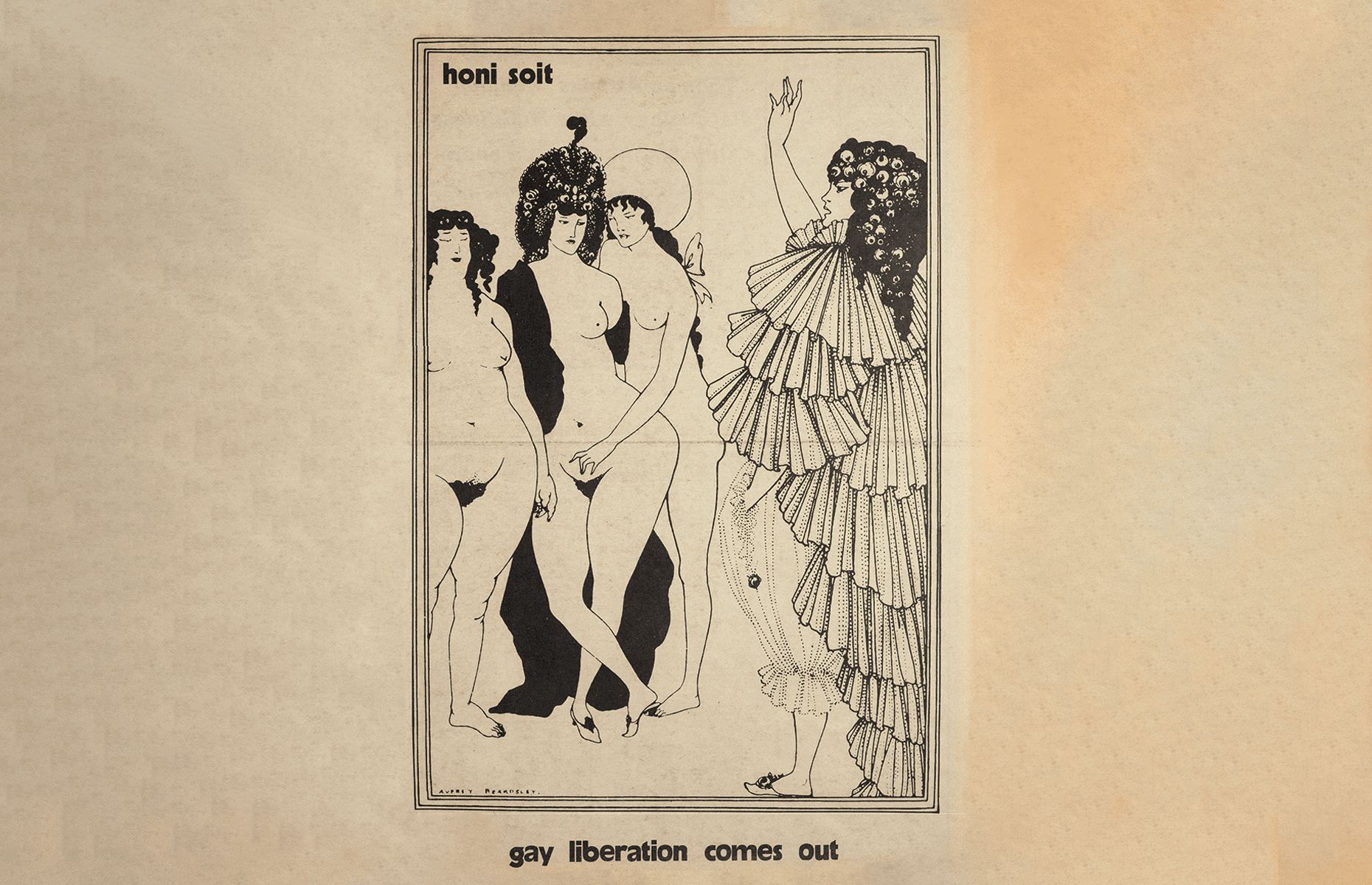

Acting as microcosms of broader society, universities have long challenged the Australian political zeitgeist with students at the forefront. As breeding grounds for the bright minds of the next generation, universities have a legacy of activism and protest — one which proudly continues today. This legacy becomes particularly apparent when we look back on queer activism and the birth of the gay liberation movement on campus.

The gay liberation movement, which took flight in the 1960s, urged queer people to engage in radical, direct action that countered the criminalisation of homosexuality, workplace discrimination, and societal disapproval. Although the movement had been gaining traction following the decriminalisation of homosexuality in Britain in 1967, its genesis is often attributed to 1969 with the Stonewall riots which were a response to oppressive police raids on gay bars in the United States. From this initial spark, the movement burned its way across the seas to Australia and to the grounds of The University of Sydney (USyd).

In the years immediately preceding this movement, queer campus activities remained relatively undergound. Although isolating, this subterranean community was a necessary element of queer surivial on campus. Sex between men was illegal in NSW until 1984, whilst lesbianism was largely unrecognised. Despite this, and in the absence of a visibly defined LGBTQIA+ campus community, queer individuals inevitably craved connection. The Honi Soit archives document this longing, recording one woman’s desperate attempt at meeting other queer women on campus. For two consecutive 1969 issues, she submitted the same earnest question: “Is there a lesbian club on campus? If so I would like to join. If not, is anyone interested in forming one?”.

Fortunately, just two years later queer communities on campus began to occupy significant social space. This began with the USyd branch of the Campaign Against Moral Persecution (CAMP), established in 1971 as part of a larger Sydney movement. Founded with the intention to both promote the rights of the queer community and alleviate the loneliness and isolation felt by many queer individuals at that time, this was one of the first queer activist groups in NSW to gain sigificant social traction.

This organisation had a profound impact on campus life because it finally provided a platform through which queer students could connect and socialise. In a 1971 interview with Honi Soit, participants Alan and Lexi describe how prior to Campus CAMP, they struggled with feelings of isolation. Lexi lamented that she endured six whole years of university before coming across another lesbian. Through this, it is evident that Campus CAMP served an integral role in the social, and likely cognitive, wellbeing of queer students.

However, as a result of society’s prevailing conservative values, the club’s conception was not without its tribulations: facing significant social and bureaucratic barriers before it could register as an official University society. The University management were resistant to permitting the club’s existence, arguing that it was “consorting with reputed criminals” and encouraging students to break the law. Only after the group threatened to “take the issue to the Front Lawn” did the administration relent and allow Campus CAMP’s formal registration. With weekly meetings held Wednesdays at 5pm in the McCallum building, the group stood staunchly against oppression in all social institutions; the University, the family, the church and the media.

Campus CAMP laid the seeds of social revolution on campus, and paved the way for other gay organizations to form. Notably, in 1976, the USyd campus became involved with the larger Sydney-based Lesbian Feminist Collective, which advocated for the unique needs of queer women. This group organised workshops and social activities and brought a much needed feminist perspective to the gay liberation movement. The group formed as a result of a larger conflict in the queer community; with some gay men refusing to accept that feminism is relevent to homosexual oppresion, and that persecutions faced by gay men and women are different. In contrast, the Lesbian Feminist Collective argued for lesbian seperatism, which affims female sexuality outside the bounds of the patriarchy.

Of similar social importance was the USyd Gay Sports Union, formed in 1976 with the objective of providing a safe environment for queer individuals to compete socially in various sporting games. This was of particular importance to queer communities given the heterosexual-dominated world of sport and the rigid gender roles that are associated with it. A 1976 notice for this group humorously entices participation through the advert: “So bewared straight sportsmen! Homosexuals are going to prove our prowess and subvert your sacred sporting institutions. Dare you scrub with an Oscar Wilde memorial team?” The Honi Soit archives document numerous successful matches against other university teams, attesting to the Union’s success on and off the field.

Despite these triumphs, it is important to recognise that as the gay liberation movement grew, so did the resistance to it. Notably, former Prime Minister Tony Abbott, the 1978 SRC President, ran for office on an anti-gay platform, during his campaign fighing vehemently against “homosexual proselytism” and “millitant feminism”.

In the face of these tensions, queer activism on campus continued to thrive throughout the 80s and 90s, serving both social and political functions that contributed to legacy of protest and resistance at the University. Today, the baton of defiance has been passed onto new queer groups; the Queer Action Collective, and the social society SHADES, both of which continue to serve a vital role in the wellbeing of queer students.