Located behind an otherwise unassuming wooden door, the Quadrangle’s Clavier Room holds one of the University’s greatest treasures: the War Memorial Carillon. Pass through one of two Tudor entrances that flank USyd’s Clocktower, climb up two flights of stairs that wind through the ancient interior (those with a keen eye might even catch the cosy Philosophy Common Room tucked inside), and the airy room reveals itself. It was here that I met with the University Carillonist, Amy Johansen.

The anatomy of a 94 year-old Carillon

This is where the magic happens.

Adorning the walls are black and white photographs commemorating the carillon’s beginnings in 1928, past figures, and the carillonist team currently presiding over the instrument. A dormant grand fireplace sits idly in another corner, waiting for a spark to light a flame in its heart. Showing me to the demo bells and the main instrument, Johansen plays a few sounds by lightly punching down the wooden batons that protrude from the device.

“You see, the batons, they’re like broomsticks. You play them with your fists and that’s the treble that you would have on a piano. Then, with your feet, you play the bass parts,” says Johansen, softly lowering one of the batons to create a low, reverberating sound.

As a carillonist plays the batons below, like a ventriloquist, strings prompt the clappers attached to hit the John & Taylor Co. bronze bells above. When these elements are coordinated, they are capable of replicating a vast array of music.

“When you really want it to be beautiful and soft, you have to hit a very, very soft note. Sometimes it’s in the feet, sometimes it’s in the hands, and it makes the sound very beautiful. How do you hit it more loudly? You put a bit of a wrist into it to give it a bit more ‘oomph’.”

Imbued in the room is a palpable sense of tradition and excitement, each drawer holding copious amounts of songsheets stacked over the years. This, after all, is a 94-year-old instrument, predating Honi Soit by one year, played on countless numbers of graduations, conjuring classical hits, the Game of Thrones soundtrack, and even The Little Mermaid’s ‘Part of Your World’.

One artefact that encapsulates the vicissitudes of time that the carillon has witnessed is a copy of Martin Shaw, Henry Coleman, and T. M. Cartledge’s National Anthems of the World (1975). Inscribed within these pages are the now defunct anthems of former Czechoslovakia and South Vietnam; there is no doubt that carillonists of bygone years would have wrestled with the political questions of their respective eras.

Johansen on being the Carillonist

Johansen is, in many ways, an embodiment of the carillon’s sense of tradition and innovation. Born into a family of musicians, she found a knack for the piano and then the organ. In 1972, she began work as an amateur organist in the Lutheran church at age 12. Following this, she cut her teeth at the University of Florida and Cincinnati’s renowned College-Conservatory of Music.

Despite her wealth of experience, Johansen is quick to pay homage to those who came before her. She modestly shares that she has been the University Carillonist since 2010, replacing Dr Jill Forrest AM who served for 27 years before Johansen took on the helm. This comes despite the fact that Johansen has been playing since at least 2003. Speaking fondly of her predecessor, she says: “We chatted a bit and she showed me the carillon. And then the next thing she said was: ‘See you on Tuesday for your first lesson!’”

From that encounter onwards, Forrest became a key mentor to Johansen’s journey in her years at the Clavier Room, responsible for teaching the tight-knight family of Honorary Carillonists who take turns playing the instrument.

“She taught many of us who are still here and she has retired but we all thank her for her help with us all. We still see her from time to time.”

Each carillonist brings with them an individual flair to the room. Having performed on many carillons across the globe, Johansen reserves a special place in her heart for Sydney’s carillon, vastly preferring the serene Quadrangle to its counterparts at Yale and Princeton.

When asked about whether she supports the alternative proposal for the carillon — a freestanding 70-metre campanile bell tower standing where Fisher Library’s coffee cart is today — Johansen is adamantly against the idea, citing practicalities and the Quadrangle’s aesthetic appeal as reasons behind her opposition.

“We’ve got 77 steps to get up here,” she says, pointing to the stairs leading to the room. Had the plan succeeded, the campanile would have easily dwarfed Australia’s only other carillons in Bathurst and Canberra. “When I think of it [the Campanile], I think of European cathedrals. So no, I wouldn’t have liked to climb up 200 steps or maybe more.”

Put in context, London’s Westminster Abbey, a comparable 70-metre structure, consists of a sweat-inducing 251 steps. No wonder Johansen prefers Sydney’s approach.

Treating us to a song of our request, Johansen demonstrates A New England by Billy Bragg— an artist famed for his rendition of The Internationale, a radical leftwing song still sung today, most recently at the strikes on campus.

“I like to play music that people request,” she explains. “So we’ve got this request that I tell people about and then people like you take them on!”

Although COVID-19 grinded the weekly recitals and Clocktower tour that used to happen every Sunday to a halt, Johansen is determined to bring these features back in the near future. Prior to the pandemic, students and curious visitors alike were able to request songs and climb up the tower. Ascending one of the Tower’s four turrets via a narrow spiral staircase, and passing a pair of crocodile and kangaroo gargoyles, visitors were treated to the sight of the bells at work and spectacular views of the Camperdown campus.

It was also here, perched in the Clocktower, that a young would-be Prime Minister, Anthony Albanese, made his stand way back in a 1983 protest with fellow activists from the Department of Political Economy.

Thus, despite the countless generations who have enjoyed this treasure, an opportunity to showcase one of its greatest assets has been well and truly missed by the University.

For whom does the bell toll?

This question, asked by Sean O’Grady nearly a decade ago in a nod to Hemingway, remains ever- relevant. Generations of students and carillonists have come and gone through the doors of the Clavier Room. And it is the student community that has motivated Johansen throughout the past two decades.

“Watching people have fun when I let them come and play,” adds Johansen, beaming from ear to ear. When the tours ran, students and visitors would leave their impressions behind in a timeworn, lovingly ragged guestbook.

“When it comes to those days they have for welcoming new students [Orientation], that’s always the best thing, when they write their thoughts about what they liked about their time here.”

Nowhere is this sense of community more evident than carefully preserved notes from students, staff, and well-wishers tucked under the glass covering of a table at the Clavier Room.

“For the world’s most wonderful carillonists – some tiny treats to say thank you for all the music,” one note says, “From all the listeners, with much appreciation and admiration.”

Another remarks: “Best New Year wishes, Carillonists, with lots of wonderful music!”. Each testimony, etched in their paper chrysalis state, stands as a witness to the organic community built over the decades.

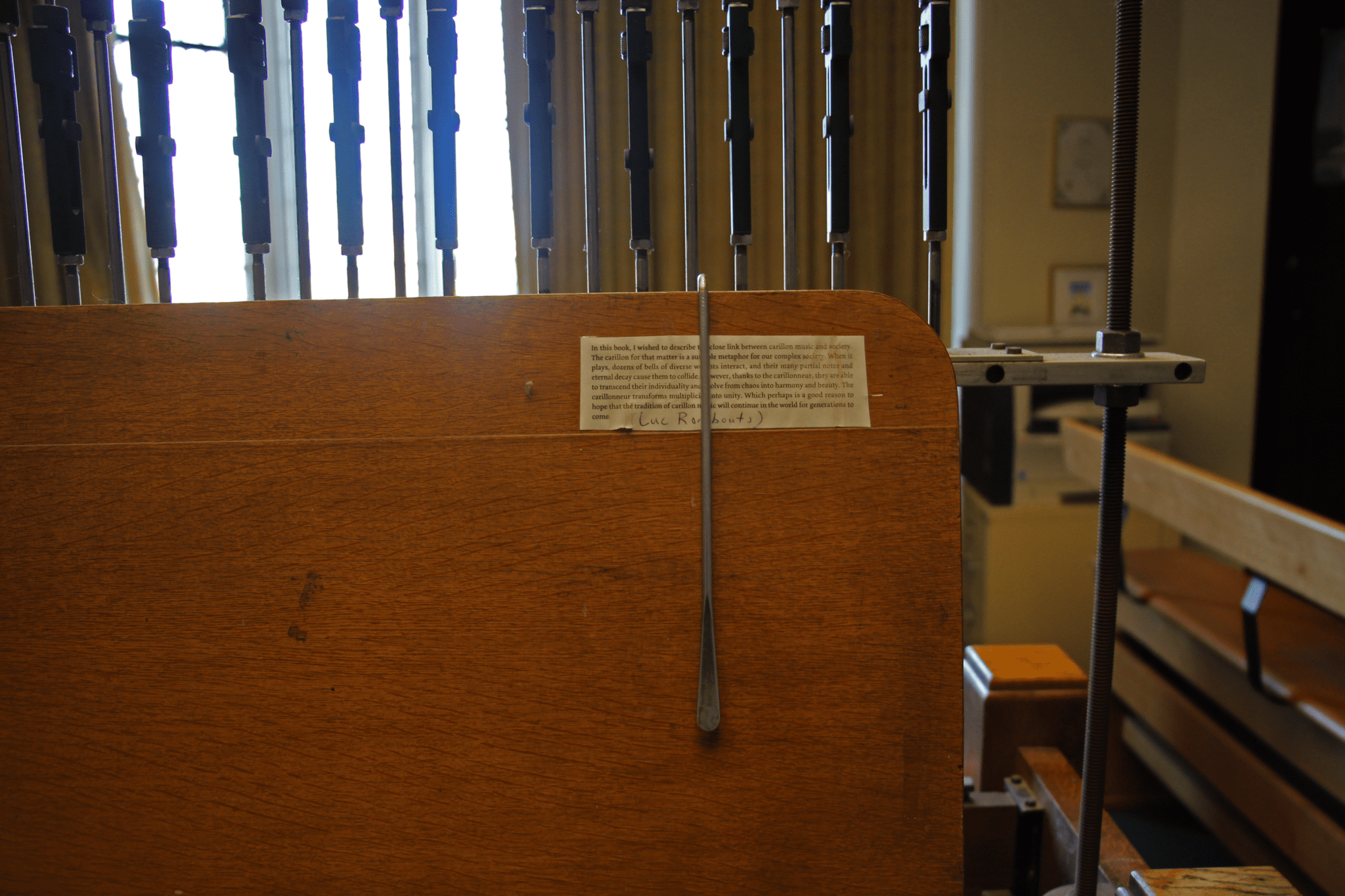

It is hard to ignore a cut-out extract from Belgian carillonist Luc Rombouts’ Singing Bronze: A History of Carillon Music that carefully frames the right-hand corner of the carillon, reminding its player of the humane values the instrument represents.

“The carillon for that matter is a suitable metaphor for our complex society. When it plays, dozens of bells of diverse weights interact, and their many partial notes and eternal decay cause them to collide,” Rombouts said, reflecting on the similarity between the Carillon’s multiple parts and the mutual interdependence that our existence relies upon.

“However, thanks to the carillonneur [sic], they are able to transcend their individuality and evolve from chaos into harmony and beauty.”

It is clear that the carillon has long transcended its original purpose, serving as a modern emblem of USyd’s raucous student life beyond the shadow of its sombre origins. It no longer just embodies the toll of war, but celebrates academic life in all its colours.

In other words, the carillon is firmly embedded in the social fabric of the University community, preserving, in its own way, a form of institutional knowledge.

This institutional knowledge is bound up in the carillon’s music, representing restless student debates, learning, and unyielding activism — knowledge that the Tower’s ornate Perpendicular tracery can never replicate. As Ronald Barnett argued in The Idea of Higher Education (1986), the university is not a collection of vain sandstone edifices but a collective of students colliding together, at times haphazardly so, towards the common good.

And so, during graduation seasons when the tunes of Gaudeamus Igitur rise from the tower, remember that the bells toll not for the grandeur of the building, but for the social bond created by the community that funded the bells all those years ago:

“Down with sadness, down with gloom,

Down with all who hate us;

Down with those who criticise,

Look with envy in their eyes,

Scoff, mock and berate us.”

Know then that the bell chimes for academia, for the cheeky grins and purposeful delinquency of student life, and, most of all, the humanity that constitutes the university community.

Let’s hope we may yet see the magnificent recitals and tours return, so that we too can bask in the view from above.

Sign this petition here to call for the Vice-Chancellor and Campus Infrastructure and Services to reinstate the Carillon Recitals and Clocktower Tour. Students can submit song requests to Amy Johansen at amy.johansen@sydney.edu.au.