When called to explain the value of poetry, it’s easy to assume a defensive stance. “Ever since poets were banished from Plato’s republic,” writes poet and critic Sarah Holland-Batt, “poets have been playing defence, writing manifestos about how poetry alone can reveal universal truths, transform the imagination and grapple with the sublime.”

It’s true that lovers of poetry can see ourselves as last defenders of the form, which god knows is an increasingly marginal one in our institutions and literary cultures. But I suspect it’s risky to play the defence in this way, to argue a bigger space for poetry in Australia by making sweeping claims about what poetry alone can do. Better to look directly to the complex, formally inventive, and unashamedly political work being produced by our poets today – work that is both proving and reconfiguring our ideas about poetic forms’s power.

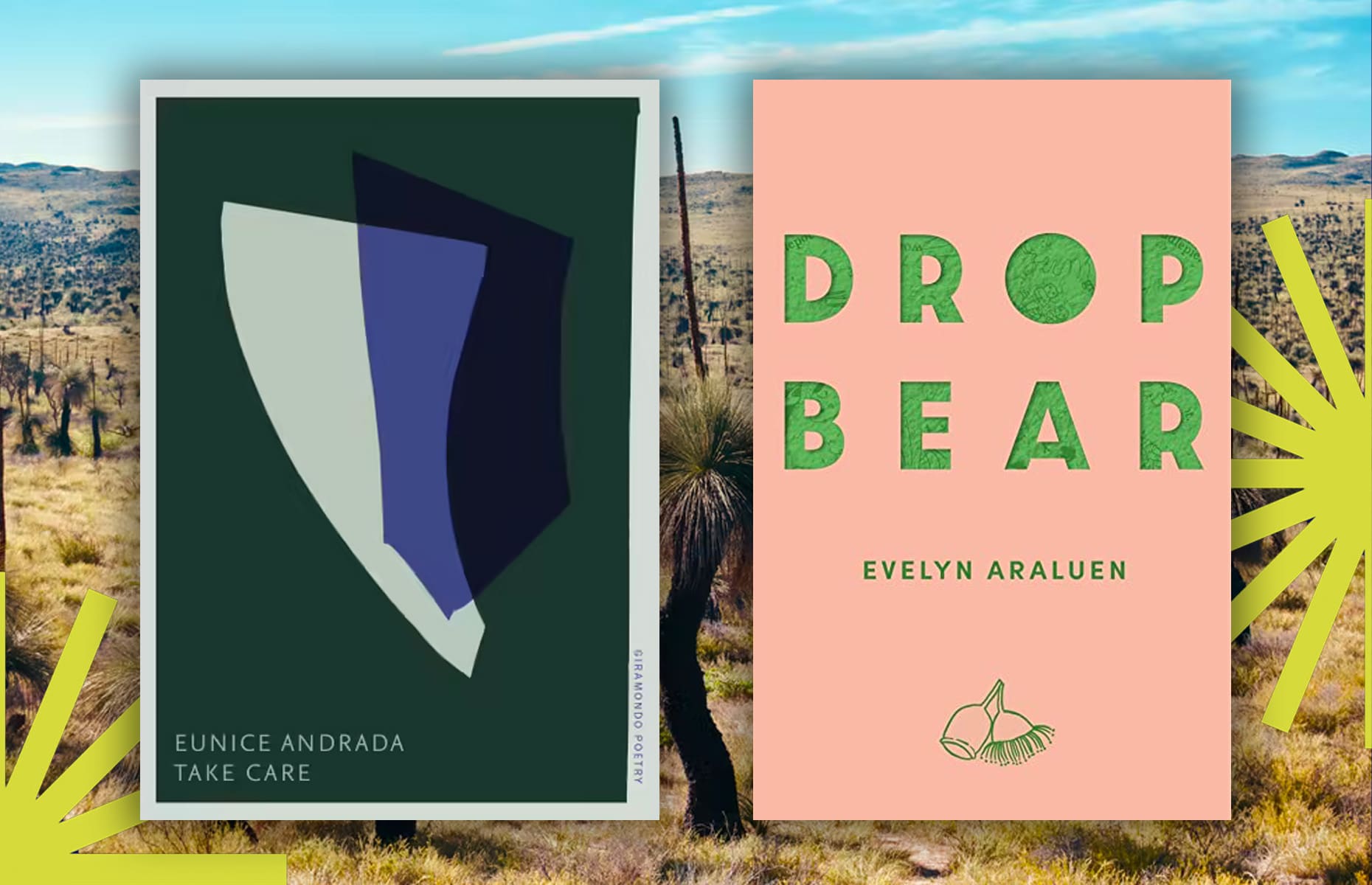

Bundjalung poet and critic Evelyn Araluen’s Dropbear (UQP 2020) taking out the 2022 Stella Prize last week is a brilliant testament to poetry’s relevance to our moment, as is this collection itself, whose experiments in voice and form reckon with various interlocking forms of colonial violence. This is the first year poets have been eligible for the Stella, Australia’s richest prize for women and non-binary authors, and Araluen is joined on the shortlist by Illongo poet Eunice Andrada’s gorgeous second collection Take Care (Giramondo 2020).

Dropbear is unrelenting in interrogating what it means to be complicit in colonial violence, whose regimes are always both material and discursive, real and symbolic. Much of the work engages directly with settler colonial literature and its continuing displacement of Aboriginal sovereignty. Poems such as ‘Mrs Kookaburra Addresses the Natives’ and ‘Fern up Your Own Gully’ riff off May Gibbs’ Snugglepot and Cuddlepie or Bill Kroyer’s Fern Gully to satirise what ‘Playing in the Pastoral’ coins “the settler move to innocence,” the kitschy gumnut aesthetics by which settler culture has sought to paper over the anxieties of its presence on stolen land.

Araluen is fiercely intelligent as a critic of coloniality – Dropbear is clearly the result of years of thinking about colonial aesthetics – but she is also simply a brilliant poet, and one of my favourite things about Dropbear is how assuredly her address balances irony with seriousness, playfulness with genuine rage. ‘Mrs Kookaburra Addresses the Natives’ has fun ventriloquising the settler’s move to innocence, “Humans! Please be kind/ to all Bush Creatures™/ and don’t pull flowers up by the roots,” but by the time we reach the poem’s end the very real violence of this discursive regime is clear: “the wicked Banksia men” are “godless fiends,” their language for land “a foul old word/ we don’t say here.”

Andrada is similarly invested in critiquing the real and symbolic violence of colonial modernity. Her poems recover and remember the bodies of women of colour lost to recorded history: wartime “comfort women” enslaved and raped in the Philippines, Filipino “diving girls” sent pearl hunting by the state. These invisible and disposable bodies are not only recovered from history, however, as the ‘care’ of Andrada’s title refers to contemporary structures of gendered labour by which women of colour are exploited under racial capitalism. Filipino women “comprise a third of all COVID fatalities in the US healthcare industry,” we are reminded in ‘Pipeline Polyptych,’ their labour “export-ready,” while poems like ‘Subtle Asian Traits’ and ‘Vengeance Sequence’ document the disproportionate sexual violence suffered by Filipino women in Australia and the US. But care, for Andrada, is also praxis, the habits of tenderness and relation by which women of colour find resistance in their daily lives, and these double-meanings frame the collection as it rages against colonial systems while gently restoring agency to the bodies they violate.

Andrada has a particular talent for the language of embodiment, for evoking what Aracelis Grimay calls, in the epigraph to the book’s fourth section, “the kingdom of touching… [of] things.” Time and time again the poems access the temporality of the body to counter state epistemologies that would render it variously invisible/inviolable depending on the ‘I’ to whom it belongs. In one of the collection’s most beautiful poems, ‘The Yield,’ Andrada’s speaker imagines the 170 sex workers enslaved as farm labourers in Manila in 1918 and “wonders about the small protests”: “if they sang under their breath while they worked,” “if they held hands, or prayed,” if they “slashed open the mouths of green coconuts and drank the juice in croaking afternoons.”

There are poems, too, about pleasure in these texts, about love and sex and beauty. But such privacies are never taken for granted, as privileges unavailable to some and only tenuously available to many. In Take Care’s titular poem, the speaker “lets [her]self rest” in “her temporary room,” while Araluen’s speaker in ‘Bread’ longs for an afternoon with a lover in “a city park uncompromised by state violence.” But “it’s only a matter of time for the bush the bar/ for every external to collapse into privacy,” she reminds us, and always, somewhere, there is “a pipeline splitting sovereign soil.” Poetry alone cannot do the work of undoing colony and capital; only political organising can do that. These collections are as sensitive to the limits of language as any work I’ve read. In Andrada’s ‘Etymology of Care,’ the speaker watches “strangers walk to their lovers” at her window, or “reach[ing] up/ for the ivory bloom/ in [her] neighbour’s front yard.” But “looming beyond the leaves/ are what we must destroy.”

“Meet me with tenderness,” she calls, “on the grass.”