This year on International Women’s day, I jokingly sent my mum a text that says: sức mạnh âm đạo. This translates to the English feminist slogan that I will never say: ‘pussy power.’

She didn’t understand the joke, but she understood the sentiment, and took this opportunity to remind me of the national heroines, the Trưng sisters who led an army of 80,000 and drove the Chinese out of the country during the Eastern Han Dynasty Vietnam. Trưng Trắc and Trưng Nhị established their own kingdom in Mê Linh, which lasted for three years.

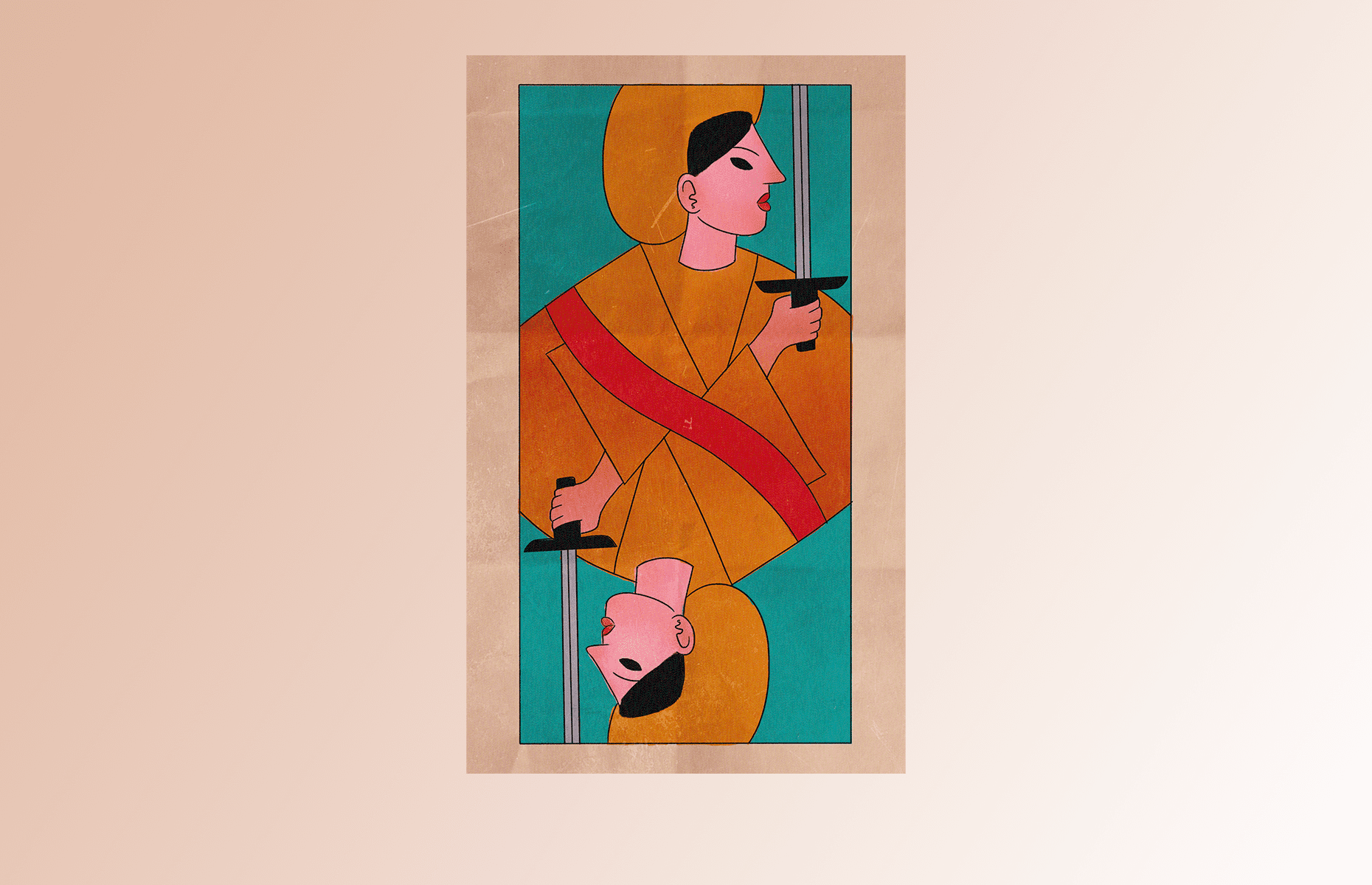

Inscribed in the national memory and Vietnamese history books is the image of two sisters riding on elephants, leading a revolution. While the sisters’ glory burns brightly in our memory, their history is recorded much more frivolously. What we have left are the archival hagiographies that chronicle the Trưng sisters’ legacy– each version crafted in the political and economic background and engraved with the moral virtues of its period. The hagiographical collection on the Trưng sisters illustrates a conflict but also progression in the historical and cultural interpretation of their legacy.

Poetry and teachings, Trần dynasty, pre-colonial

Educated within Confucian and ancient Vietnamese moral principles, scholars of the pre-colonial period narrated the sisters’ story with appraisal of their military achievements, only by way of indoctrinating these historical patriarchal and patriotic values. Historian Lê Văn Hưu wrote:

“What a pity that, for a thousand of years after this, the men of our land bowed their heads, folded their arms, and served the northerners; how shameful this is in comparison with the Trưng sisters, who were women!”

Translated by writer Đặng Thanh Lê, a poem from from the fifteenth century echoed:

“The Han emperor was extremely furious:

This insignificant speck of Giao Chi!

And it was not even a man,

But a mere girl who wielded the skill of a hero!”

In perceiving the Trưng sisters’ rebellion as the true embodiment of Vietnamese patriotism, this narration of the sisters’ achievements were employed not necessarily to propagandise Vietnamese people against the Chinese, but more to emasculate those who complied with the Chinese rule. This was another way of saying ‘Don’t you have the balls to stand up for yourself? Even the Trưng sisters are able to do it, and they’re women!’ It was almost as if the sisters’ defeat of the Chinese was disappointing, because they were women and not men. In these precolonial recounts, the story of the Trung sisters was told not entirely as a nationlistic victory, but much so as a defamation of the masculine.

Trưng Nữ Vương, a play written by Phản Bội Châu, 1911, pre-colonial.

The patriotic spirit of the Trưng sisters continued to be praised throughout pre-colonial Vietnam, and this admiration was typically infused with emphasis on the sisters’ beauty and Trưng Trắc’s romance with her husband, Thi Sách. This is most prominently illustrated in Phản Bội Châu’s tuồng (Vietnamese opera) Trưng Nữ Vương – a drama on the heroines’ lives.

The play recounts that after her husband’s execution by Tô Định, the Chinese governor, Trưng Trắc initiated the rebellion in revenge for her husband and for her love of her country. Older versions of the story depict the sisterhood between Trưng Trắc and Trưng Nhị as the fire that lit their rebellion. In this adaptation, however, Trưng Trắc acknowledges that she is a woman and fears that she cannot defeat the Chinese. Trưng Nhị, her sister, urges her to finish her husband’s business. Now is not the time to “act like ordinary women,” Trưng Nhị reminds her sister.

The portrait of a fearless woman who sacrifices for her country while mourning her husband’s death on the battlefield is nothing new in the hagiographies on the Trưng sisters. And in both Phản Bội Châu’s play and Đặng Thanh Lê’s hagiographies on the sisters, the sisters are described to have ethereal beauty: Trưng Trắc has “snow-white shoulders,” “skin of ivory,” and “a smile more joyous than a blossoming flower.” This saturation of their feminine beauty, however, was not intended to undermine women’s strength and objectify them, but to highlight the sisters’ loyalty and sacrifice for their country.

Contrasted with previous versions, Phản Bội Châu’s recital rendered a substantially more progressive portrayal of women in revolution. Though this was the case, the patriotic sentiment of the story transpires only within the drama’s antithetical plot line between beauty and femininity, and military and masculinity. A woman’s love for her country is a hand-me-down from the male figures in her life; her strength is nothing but an emulation of male leadership.

Phụ Nữ Tân Văn newspaper, Saigon 1930, under French rule.

Phụ Nữ Tân Văn was a women’s newspaper that emerged in twentieth century Saigon under French domination. The French, in their ambition to educate the literate, supported the newspaper. Still, under their dominion, anti-imperialist and nationalist sentiments had to be muffled and muted.

In their article, “Hai Chị Em Bà Trưng,” instead of Trưng Trắc’s grieving her husband’s death, the Trưng sisters are recounted as hauling themselves into rebellion for their “fervent love for the people.” Loyal to the Trưng sisters, peasants of towns and villages followed the sisters’ leadership and sacrificed their lives in the rebellion. The Chinese governor, Tô Định, in this version of the story, is described as “a coward who flees immediately” in the battle. In the end, the sisters sacrifice their lives by jumping into the Hát Giang river. The end of the article reads:

“The Trưng queen is the spiritual mother who bore Mai Hắc Đế, Đinh Tiên Hoàng, Lê Thái Tổ, and all of the more than 20 million patriots of our nation today.”

The Phụ Nữ Tân Văn’s article telling of the Trưng sisters’ legacy, once again, contrasts greatly from its predecessors. Because of heavy censorship of anti-imperialist sentiments, the Trưng sisters were painted as spiritual mothers who went into war for their love for the people, rather than patriotic soldiers who were committed to their nation. The rebellion also ended not in gory mass violence on the Chinese, but with the sisters’ sacrifice. Perhaps, in the absence of nationalist values in this column, feminist values shone through. The journal withdrew the appearance of male characters, depicting the sisters as legitimate military leaders who mobilised a rebellion on their own. Regardless of this maturity, the Trưng sisters were still drawn as delicate, mighty forebears of our nation.

Tân Dân journal, Hà Nội 1945, under French Rule.

At the cusp of the eruption of the first Indochina war, the Tân Dân, a pacifist newspaper that occasionally published radical leftist perspectives, had emerged. By then, while many women still served in the war as food suppliers and nurses, many also held active roles in politics. In the midst of war, the paper tells their version of the Trưng sisters’ legacy.

According to the article, “Ngược Dòng,” the sisters’ mother, Man Thiện, initiates the rebellion with her daughters, who are then joined by female ‘comrades’ along their way. While their mother lead the rebellion, Trưng Nhị mobilised their local community. Together, they marched under “red flags.” Trưng Trắc only fully enters the story after her husband, Thi Sách, dies from disguising as a reformist under the Chinese. Thi Sách, in this version of the story, did not initiate the dissenting action, and also earned his death for disloyalty. After her husband’s death, Trưng Trắc faced Tô Định and knocked him out herself.

Until the Tân Dân’s account of the Trưng sisters, what was missing from previous recounts, is the significance of the role the sisters’ family and community played in the rebellion. Their mother, along with everyone who assisted them on the way contributed to the defeat of their foreign oppressors. Even as a journal that was published under French rule and monitoring, this article vehemently eulogises anti-imperialist comradeship– from imagery of the “red flags” to sprinkled communist jargon, which all came together to propagandise and foreshadow the imminent revolution against the French. In previous narratives, Thi Sách’s tactic of playing with the Chinese has always been interpreted as a cunning and patriotic act. The Tân Dân article, though, renders his intermediate path as cowardice and betrayal of the nation’s revolution against our oppressors. Perhaps this served as a reminder that those who take the middle path, die. Male characters, overall, in this rendition are not painted as grand, but as dumb and disloyal. The biggest shift, most obviously, is that the success of the Trưng sisters’ rebellion did not come from male leadership but from women and their mobilisation of other women.

With every flip of an archival tale, our memories of the Trưng sisters’ legacy become figments of our imagination. But the allegory of Trưng Trắc and Trưng Nhị is far from mythical fables and rather tangible battles of the patriots of our people. The national memoir of the sisters passes through thousand of years under imperialist domination, generations of elementary school textbooks, along the streets of our cities, marking the shifts and play between nationalist and feminist values in our history.

In contrast with Western feminism, feminism in Vietnam and Vietnamese culture has not advanced as ideologically. In the language itself, feminism is simplistically encased within the term ‘nữ quyền’ which means ‘women’s rights.’ In our studies of radical feminism today, however, ‘feminism’ encapsulates the goal of ending gender oppression which pervades both the personal and the political and sustained by the intersecting systems of racism, classism, transphobia, and heterosexism. For Vietnamese people, retellings of the Trưng sisters’ story remind us that our understanding of feminism has always been inextricable from our liberation from our oppressors. If the day ever comes and I say to my mum ‘pussy power’ again, I know she knows what I mean.