Two men will soon walk into a bar. They will be reuniting after years gone by and are excited to catch up with one another. Conversation is their forte. It’s what they do for a living, but also cultivate as a hobby.

The bar is on the corner of a street: quaint, regular, reeking of beer and fried food and lowly lit too. It is far from romantic, but that doesn’t concern these two. They are friends, both married with wives and children, and are used to the atmosphere of drinking institutions from their university days.

The time is 6:37 PM, a Thursday evening at the beginning of Autumn. Both men have dressed appropriately for the cool, yet pleasant weather. The first man has taken the metro and the second has taken the bus. After walking up the stairs of the bar’s entrance, which leads to an alfresco-style waiting area, the first man sees the second man waiting by the door.

“Have I kept you waiting too long, old friend?”

“Not at all. It’s only been a minute or so, old sport.”

“You know I hate The Great Gatsby with every fibre of my being.”

“And that is exactly why I’ve decided to pick at this timeless scab. Also why you’ll never have some fantasy library girl marry you”.

“I’m afraid you are wrong there, old sport. The papers have been signed, sealed and delivered for years now.”

“I can’t wait to hear all about this love story, just as soon as we go in.”

The two men who are about to walk into a bar chuckle. They have rekindled the fires of their old friendship and are eager to continue their jovial banter inside. They approach the entrance of the bar and are checked for identification by the bouncer.

“We must be looking as fresh as ever!” says the second man.

“Twenty years later and no one can keep their eyes off us!” says the first.

They slide their identification cards back into their wallets and line up. The queue isn’t too long and moves rather quickly. There is no one behind them, nor will there be for a while. Business: it fluctuates like this.

Halt.

They both halt. The first man and the second. Halting like they have never halted before in the countless years they have known each other. The two men’s families are friends, their parents close, their wives well acquainted. Despite all this, they have failed to maintain contact and relations for several years. Though in the twenty-or-so year span of their friendship, neither has ever had to halt in the presence of the other. Not like this, at least.

“Um-” says the first man.

“Uh-” says the second.

“After you, good sir.”

“No, no, after you.”

“Please, after you.”

“I simply couldn’t.”

“But I insist.”

“And I too insist.”

“I implore you!”

“I encourage you!”

“I beg you!”

“I- I- support you!”

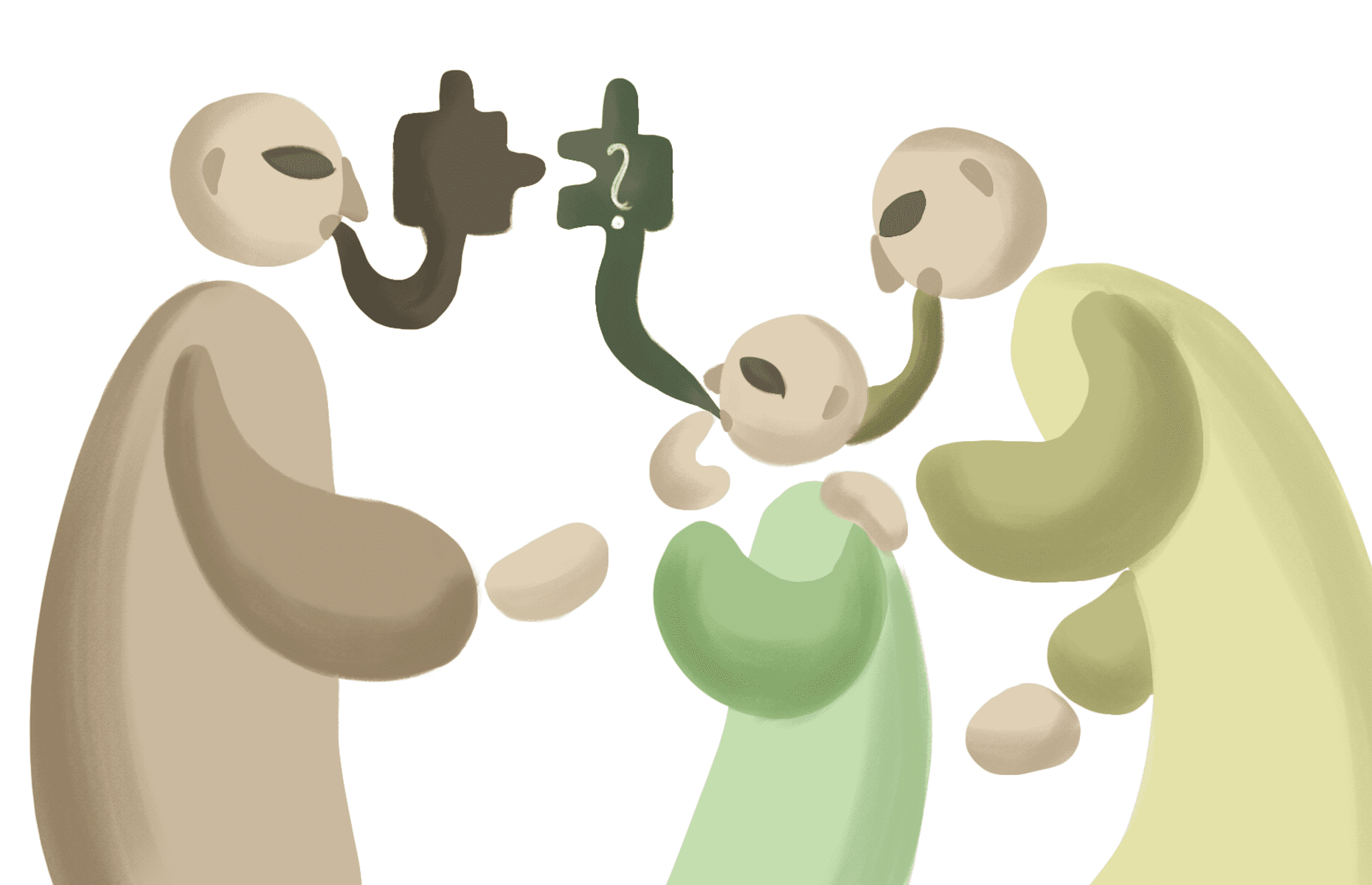

“Are you two going in or not?” the bouncer asks, his voice booming from the back of the empty line. It reverberates, hitting the two men and their quandary quite unexpectedly. The bouncer adjusts his cap, and crosses his large arms. The two men freeze. Not halt, but freeze. They have been raised this way, but were children then. Children are inattentive. They are lifeless and boring when they want to be. They are equally wild when playing, or simply choosing to be. But, in the presence of parents, nay, ethnic parents, no, Iranian parents, children live low and walk through doors and sit down and accept food and pay bills only, and only when their parents do the same. At least the good kids did. Do. And these two men were good kids.

“Sorry to cause you trouble, mate.”

“We hope you weren’t too inconvenienced.”

“Move along,” he grunts. Bouncers have it tough. Half the drama happens outside of bars, pubs and clubs.

“Well, ah, there’s only one way to settle this,” the first man says, adamant about catching up with his friend.

“I think we are on the same page here, my friend,” the second replies, also adamant about catching up.

Five minutes have passed. The two friends are now sitting outside the bar, sipping drinks at their table. The Autumn breeze keeps the men slightly chilly, but it is nothing the warmth of their memories cannot protect them from.

“Good thing the staff could bring these out for us.”

“Oh, yes. They were very accommodating.”

“And hospitable.”

“And hospitable.”

Luckily, this bar is a restaurant and bar, separated by an adjoining wall but accessible via a corridor of sorts. This is particularly advantageous to the old friends who, alongside their drinks, are hungry for the rekindling of their memories and some hearty serves of chicken parmies. And a side of chips. Maybe some salad too.

“Crispy- just the way I like it!” exclaims the first man.

“The only way to enjoy it. After you now, good sir.”

“No, no, you are eldest by three and a half months. You first.”

The chicken parmies sit hot in front of them. team rising in an almost cartoonish fashion, like those steam inhalers people use when plagued by a cold. The men insist back and forth, forth and back, back and forth until the parmies have cooled to hardened lumps of coal. They have spent a considerable amount of time on formalities and have neglected the classic Australian meal, despite its begging for a bite. Like a fallen coconut on the heads of pirates in swashbuckler movies, the two men are struck by realisation.

“No point fussing over it now,” says one calmly.

“Of course, of course. Nothing tea can’t fix,” says the other.

Both signalling the server with the utmost respect-because everyone knows that servers in the hospitality industry have it tough-the two men reach for their wallets, whipping out two deluxe, super shiny, extra plated, thickly cut, ultimate, platinum, exotic pieces of plastic.

The server approaches them before their bickering begins and informs the gentleman that the bar’s EFTPOS machine is inside. It is not portable. Unlike the chairs and tables brought for the two men outside, the EFTPOS machine cannot be moved from its place. Offering to take a card, and arrange the payment inside the bar, the server is dismissed and approaches her manager with an unusual request.

“Can never trust anyone with money, my friend.”

“Especially nowadays, with all you hear in the news.”

Shortly after the two men converse politely, the manager and server appear, pushing a large countertop through the door of the bar, gripping its corners in a one-two-three-HEAVE! method. The bouncer, seeing how heavy the counter is and noticing that it has no wheels and that the EFTPOS machine might be ruined in the process of relocation, stops the struggling duo and runs to his car. The two men simply watch, caught in the embarrassment of their requests. The bouncer returns with an extension cord. In a few brisk moves, the bouncer connects the EFTPOS machine to the extension cord and the extension cord to the power point inside the bar. Without hesitation, he slams the machine onto the gentlemen’s table and marches back to his post. This time, with a flurry of grace and humility, the two friends push each other’s hands away from the machine, as the cards play an unsolicited game of slaps mid-air.

“I couldn’t possibly allow you to pay for this meal when it was I who suggested this outing.”

“My dear friend, I was the one who accepted and recommended this place for tonight.”

Back and forth they go. Seconds becoming minutes and minutes becoming an hour and a half, occasionally interspersed with small talk. The old friends, so enthused to see one another again, have barely shared the details of their adult lives all evening, a duel of plastic cards hindering them altogether.

In a sudden rush and stampede of footsteps, the server, manager and bouncer, followed by a herd of diners, drinkers and staff, storm towards the two friends seated outside. The bouncer gains speed, his eyebrows tangled in a fury and heels at the table like a rodeo bull. Raising his mighty fists, he reaches for his cap and throws it on the table, which lands between the chicken parmies.

One by one, the bouncer, manager, server and their followers empty their pockets and place five, ten, and twenty-dollar bills into the bouncer’s cap. The bouncer hovers close by, watching the village obediently pay their taxes until the last person throws in five dollars and twenty cents.

“Keep the change.” He grunts, following the rest of the people back inside.

The bouncer remains, now towering above the two mates who have stayed silent this entire time.

“Your meal and drinks have been paid for. You may leave.”

In one swift movement, the bouncer picks up the table without spilling a single thing and heads inside, slamming the door shut and leaving the two men on their chairs outside. It’s quite dark now and the night seems to be settling into its, well, nightly routine. Nocturnal animals are out and about and the Moon plays its symphonies for its devotees, as the stars and the cool Autumn breeze creep up the spines of trees.

Having not spoken to each other, nor anyone else, during these proceedings, the friends stand abruptly, tucking their chairs underneath an invisible table, and head down the steps of the bar’s alfresco terrace entrance and into the car park. A timidness fills the air, stifling the previously refreshing Autumnal breeze. That kind of wind revitalises, but this kind of wind withers. It freezes and sends things, people, concepts, and old ideas into frost. Conveniently, the two men end up next to the taxi bay of the car park and in a few short exchanges agree to take a taxi home together. After tonight’s situation, they avoid talking about the taxi fare. It is safe to assume that it will be split fifty-fifty. Or will it?

The taxi driver greets them and presses a button that opens the car door. No need for handles; these are things of the past. Silently, the two old friends who were not able to walk into a bar, enjoy their drinks, pay for their food and socialise efficiently, stare at each other with complete and utter confusion. They freeze, as if a Winter wind has infiltrated the very marrow of their bones. Stagnation consumes their bodies, and they are paralysed, once again, in a moment of uncertainty.

And so, The Ancient Dance of the Doors begins again.