Steve Irwin. Backyard cricket. Vegemite on toast. What do we think of when we think of Australia? Beyond a few cultural icons that get thrown around when we discuss “Aussie” stereotypes, the precise nature of the Australian identity remains less clear. We are a nation primarily made up of immigrants, yet we continue to exhibit racism and bigotry. With Federation occurring a little over a century ago, we are a relatively young nation, yet home to the oldest continuous living culture in the world. We exhibit both incredible diversity and incredible bigotry. If we do find an answer to the question of what Australia means to us, how can we convey it?

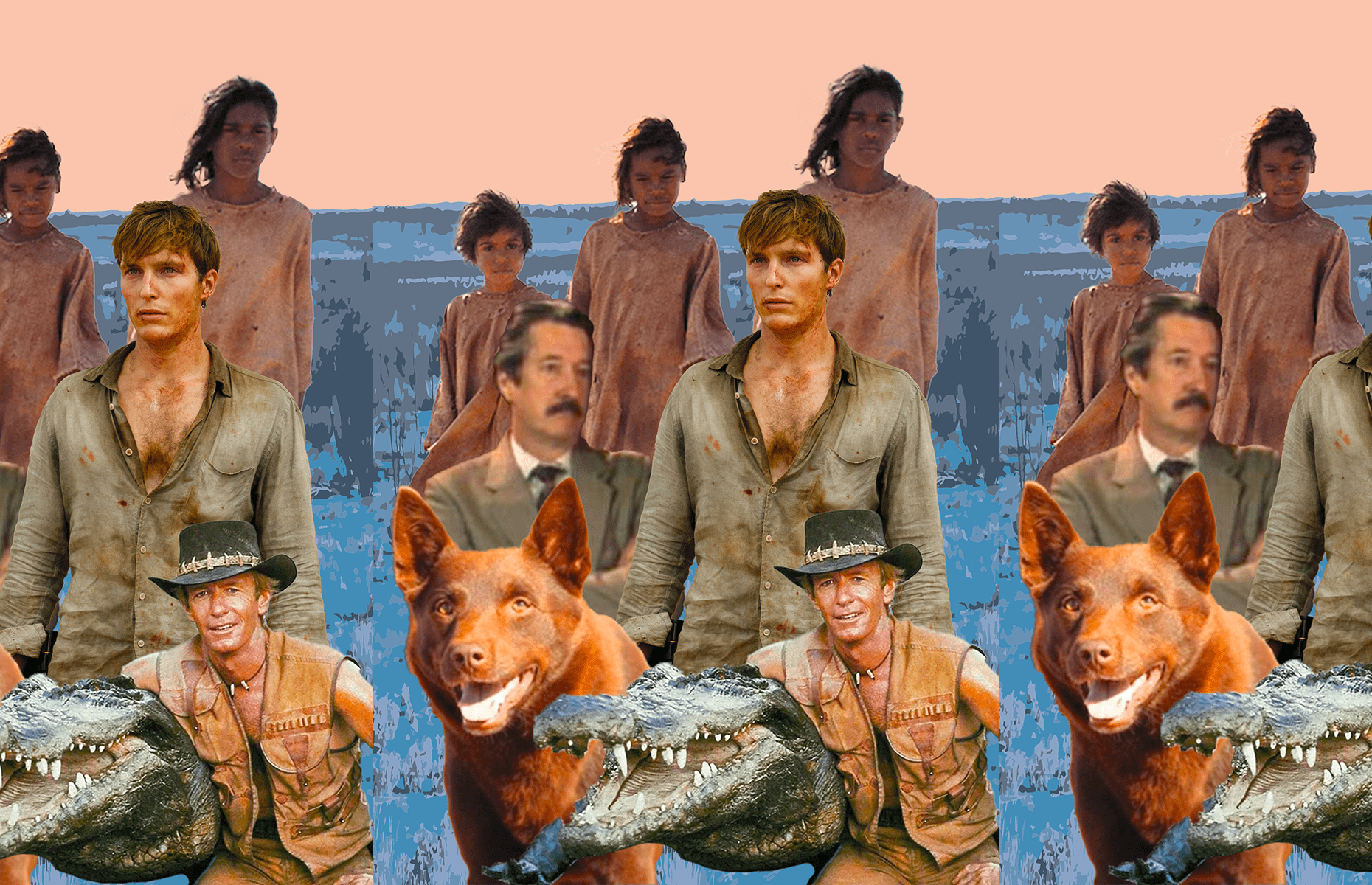

Cinema is one such answer: as an accessible medium that possesses a tremendous capacity for storytelling, it has been used to express unique and diverse Australian identities and share them across the globe. From Red Dog (2011) to The Castle (1997) to Crocodile Dundee (1986), cinema has played a pivotal role in shaping how Australians view themselves, and how the world views Australians. Art is special like that – its roots in emotions, humanity, and storytelling can establish, further, or challenge our worldviews.

Across the Pacific, the US has fostered the idea of the Great American Novel – the concept that a singular work of art can embody the essence of America. Australia, unfortunately, has dedicated little toward finding our own equivalent: a singular work of art that can capture our national identity, novel or otherwise. We bear a strange sense of cultural cringe towards Australian art, as though the art that we produce could not possibly compare to the great work of other global film and literary industries.

Given Australia’s position among the highest movie-watching nations in the world, one imagines that there would be a number of contenders for the title of Great Australian Film. Yet, whether a single film is capable of achieving such the colossal task of ‘embodying the essence’ of a nation is a matter of debate. I have therefore compiled a set of films that, when put together, represent Australia’s multi-faceted and ever-elusive identity: Rabbit-Proof Fence (2002), Wake in Fright (1971) and The Castle (1997).

Adapted from the novel by Martu woman Doris Pilkington Garimara, Rabbit-Proof Fence tells the true story of three Aboriginal girls from the Pilbara who, after being forcibly removed from their families by the government, evade authorities to make it back home. Aside from being an incredibly well-directed work of art, the film’s exploration of the Stolen Generations serves as a disturbing portrait of Australian white supremacy and its human toll.

Among the reasons I included Rabbit-Proof Fence on this list was because of its representation of and engagement with Indigenous Australia. The invasion of Australia in 1788 and the propagation of the terra nullius myth is, in many ways, Australia’s original sin. The effects of it can be traced throughout our history and are still felt today, manifesting through issues such as disproportionate representation of Indigenous youth in custody, deaths in custody, and the trauma of the Stolen Generations. It stands as one of the Great Australian Films because of the mastery with which it brings one of the most shameful moments of our history to life – history that is all too often taught in a detached manner through school, or whitewashed by conservative politicians or media outlets. Rabbit-Proof Fence demonstrates the power of cinema and storytelling in its bold and heartrending depiction of one of the most shameful episodes in Australian history.

Best described as an Australian Heart of Darkness, Wake in Fright explores the nature of Australia’s “larrikin” identity, and whether it is something we should be proud of. The story follows John Grant, an Englishman who works as a teacher in the middle of the Australian outback. En route to Sydney at the end of semester, he finds himself in the blokey, hard-drinking town of Yabba. What unfolds is a psychological thriller as Grant loses his grip on reality amidst the drunken excesses of Australian masculinity. What makes Wake in Fright so terrifying is its accuracy in portraying the worst of our national character – alcoholism, ignorance, and violent masculinity.

Among the most incisive scenes in the film occurs not even half an hour in, when Grant finds himself at an RSL, amidst a sea of drunks playing the pokies. The music, yelling, and swearing is at fever pitch; an omnipotent roar fills the entire club. Then the noise suddenly cuts off and everybody rises to stand still, frozen as the lights dim around them. A booming voice bellows through the speakers: “They shall not grow old… Lest we forget.” For a moment they hang there, suspended in the silence with blank, wide-eyed stares into the distance. Then the lights and music roar back to life and they slink right back into their drinking and swearing and gambling. The film is filled with moments such as this – deeply unsettling portraits of a “larrikin” Australia that is crude, drunk and lacking self-reflection.

Perhaps there’s something to be said of the fact that the director, Ted Kotcheff, isn’t Australian. Born in Canada to Bulgarian parents, Kotcheff’s background arguably gave him a greater perspective to understand how Australians perceive themselves, and how the world perceives Australia. Wake in Fright stands among the most deeply disturbing and unnerving films ever produced, and its bold dissection of our national identity makes it a must-watch.

If the former films represent the worst aspects of our national history and character, The Castle serves as a touching reminder of the very best that Australia can aim to be. The blue-collar Kerrigan family work together to protect their family home from being demolished by faceless men in the government and the private sector. It remains one of the most-quoted Australian films of all time, a testament to its picture-perfect representation of Australian suburbia. It’s hard to pinpoint the moments that make The Castle so quintessentially Australian. Whether it’s the mementos that go “straight to the pool room” or the mindlessly repetitive song that is sung on the way to Bonnie Doon, it expertly captures the intricacies of Australian family life.

Released at a time when conservative politicians and media outlets were leading public discourse against the 1992 Mabo High Court decision and the Keating Labor government’s Native Title Act, The Castle acts as a parable that helps non-Indigenous Australians comprehend the significance of land rights and the connection people have to the land they call home. Yet, it also celebrates Australia’s migrant population, with Italian, Greek, and Lebanese characters in prominent roles. This was particularly special for me as a Greek-Australian, because it marked the first time I saw a Greek on screen, in the form of the kickboxing-obsessed Con Petropoulos. In cutting across multiple aspects of Australian society, The Castle embodies, as Dennis Denuto would put it, the “vibe” of Australia in a manner that few films have accomplished. It remains not only my favourite Australian film, but one of my favourite films of all time. It’s a Great Australian Film because it’s accurate, it’s heart-warming, it’s the vibe and – no, that’s it. It’s the vibe.