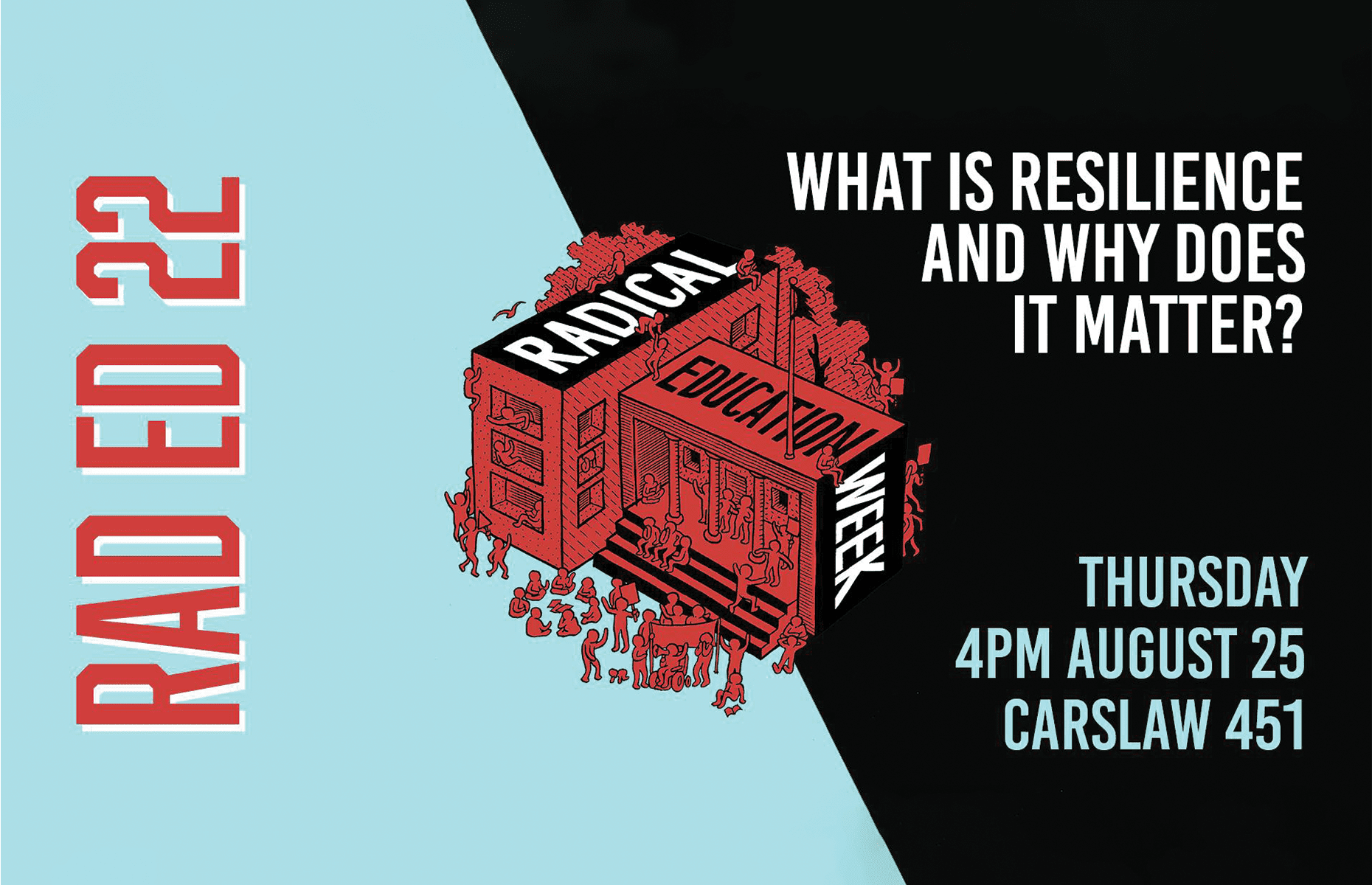

In a climate that constantly conspires to break you, holding your last shreds together is radical. Thought-provoking and ephemerally motivational, Kalantar’s talk on ‘Resilience’ for Usyd’s Radical Education left a lingering feeling of hopefulness in us.

Jahan Kalantar is a Sydney-based human rights lawyer, mental health advocate and entrepreneur. He is the most popular among students for sharing his quirky legal TikTok and being a senior solicitor in the USyd Students’ Representative Council (saving students from academic misconduct, bless!).

The event was a warm affair with a dozen attendants both online and in-person. The tight-knit setting, filled with casual conversations, discussion about resilience and Kalantar sharing his life experiences was a perfect midweek pick-me-up session. However, the forum did not shy away from discomfort as he began by sharing how he learnt the most about resilience through working with those in custody, refugees and marginalised by the system.

What grounded Kalantar’s belief in resilience was the way he acknowledged the problematic nature of institutions like prisons, especially forensic prisons, that keep “extremely mentally distressed” individuals in captivity.

Does he dwell into the problematic nature of prisons? Not really.

Is the conversation centred around those estranged by the system? Neither.

However, he does consolidate a stimulating conversation around hope and empathy towards those in need, and how it teaches us resilience in the long run.

“Hope is a discipline,” says abolitionist and academic Mariame Kaba. By sharing anecdotes of his early work with those in forensic prisons, Kalantar dwells upon the discipline of hope with how he unfurls the necessity of staying together in the face of adversity.

In addition, Kalantar addressed three aspects that aim to help enhance students’ mental resilience. First and foremost, he directed us to think about being a stone, which is to believe that there will be an island for you to stay somewhere.

Gratitude is another suggestion that he provided to the audience. Sharing a story about a refugee who came to Australia to seek a better life, he talked about a touching moment when the man kept thanking him only due to a tiny act of kindness that he did as a professional. Remarkably, the things that we are sniffy about can become the most valuable things for others.

“Resilience is not something you are born with, but it is something that you learn,” Kalantar asserts at several junctures. Although a common sentiment, it mingled perfectly with gratitude as it leaves the audience to think about the numerous political privileges that we are endowed with. Sharing his own struggles with anxiety and depression, he reiterates that gratitude makes waking up everyday to a hopeful morning possible.

In talking about political privileges for refugees in Australia, there is a slight deviation from the intrinsic colonialist sentiment that overwhelms the stolen land. However, his point of relative privilege for those looking for a better life in the face of tumult is well-framed and serves as a good reminder for the audience how land sovereignty is connected with the well-being of the people on those lands.

Last but not least, Kalantar pointed out the significance of being open to diverse perspectives. Reality and possibilities are interconnected with one another all the time. After talking about another case he received during his legal practice, he stressed the value of engaging with multiple viewpoints in his life. As such, stubbornness and tenacity are two-sided swords as things cannot be predicted before it happens. Why not challenge ourselves to make a change from now on?

Overall, Kalantar’s talk on ‘Resilience’ provided practical and inspiring tips for USyd students to take care of their mental health in a time of uncertainty, especially under the circumstance of an ongoing global pandemic. He showed us a picture of how understanding, improving, and producing resilience can transform ourselves, as well as the ways we perceive our surroundings.

Tertiary education with a looming burden of adulthood, tumult and political dilemmas is hard. Kalantar’s amicable demeanour and relatability gave that sombreness a fresh perspective, and a freeing one at that.