When she sat down to craft her debut novel in 2020’s lockdown, months after finishing her undergraduate degree, Diana Reid had never considered a career in writing before. An incisive debut about the interplay of sexuality, feminism, and power at an Australian university campus, Love and Virtue (2021) surfaced to overflowing critical acclaim and was named Book of the Year by the Australian publishing industry in June.

But, in hindsight, it very well might not have been written.

“It kind of terrifies me, actually,” Reid says. “I was so dependent on this very freak circumstance [lockdown] before I actually sat down and opened a blank word document.”

Reid studied Law and Philosophy at USyd, with a graduate job at a law firm lined up for the end of that year.

“I was in a really fortunate position… I was living with my parents, so I had the freedom to write because if it didn’t work, there were so many safety nets for me,” she says.

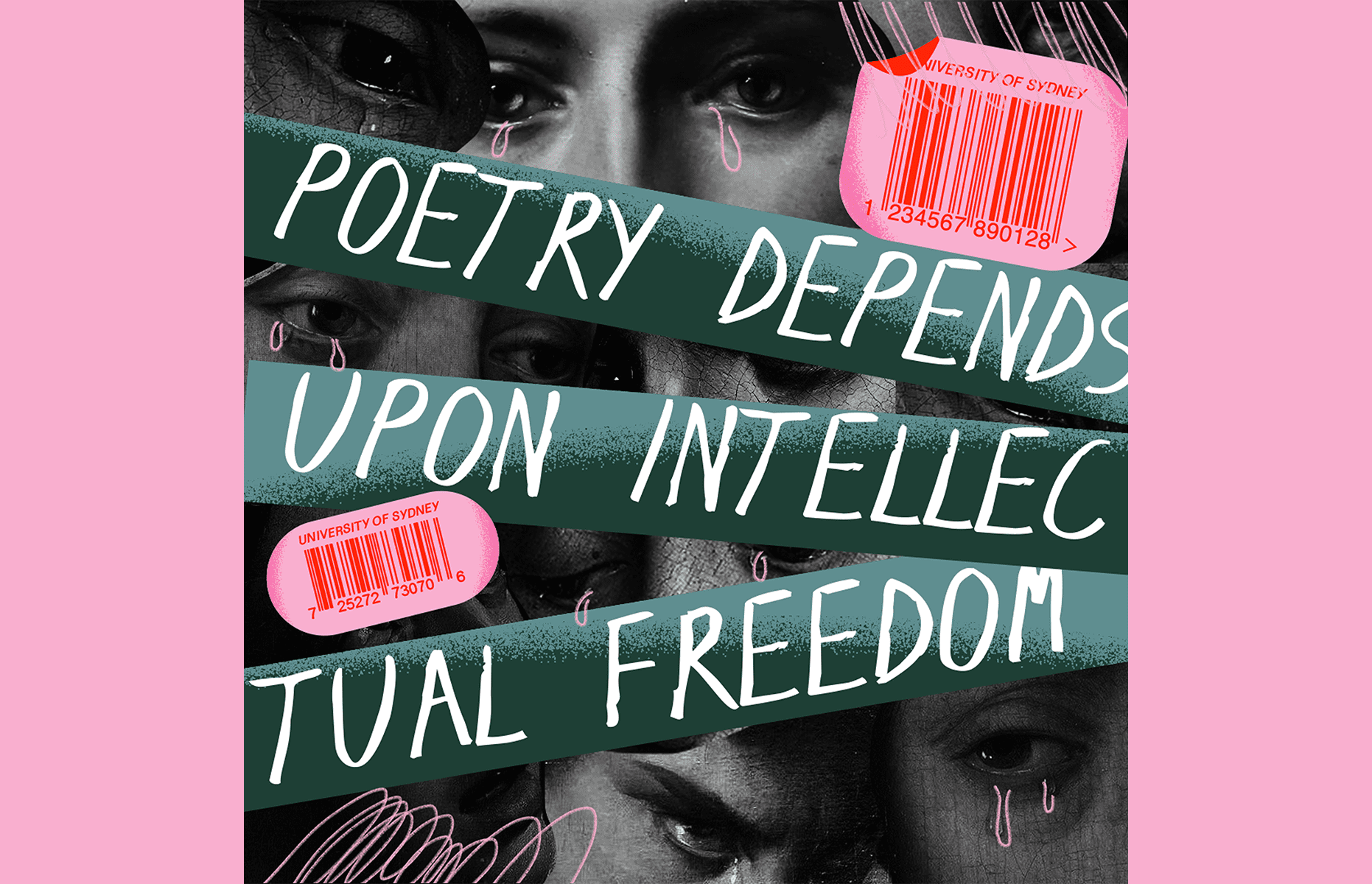

Of course, the apparent impracticality of novel-writing is nothing new. Time and intellectual freedom have always dictated the production of literature. “Intellectual freedom depends upon material things. Poetry depends upon intellectual freedom,” wrote Woolf in 1929. As these resources have, for most of history, existed in scarcity outside certain, privileged demographics, the act of writing itself has often required struggle and defiance of authority.

Though access to literacy has widened since the early 20th century, a literary career is still less accessible and less appealing to the majority of Australians than it should be. When Evelyn Araluen won the Stella Prize for her debut poetry collection Dropbear this year, Australia’s richest prize for women and non-binary authors and poets, she said she was “one paycheck away from complete poverty,” imploring governments to provide better funding to writers.

Diana Reid also notes that while she feels “very fortunate” that her novel is currently her main source of income, “it’s definitely not the norm.”

Most creative writers in Australia struggle to make a living. In a 2020 survey by the Australian Society of Authors (ASA), over half of the recipients reported making “$0-$1999” a year from their writing; almost 80 per cent earned less than $15,000 per year. This is not because book sales have depreciated. The proportion of Australians who read for pleasure (72 per cent) has increased by 17 percentage points since 2016, with novels or short stories being the most popular form of reading material (47 per cent). This was boosted by the pandemic; sales of adult fiction rose by 12 per cent in 2020 compared to the same period in 2019.

The ASA’s survey concludes that “there is a fundamental disconnect between the enormous value and importance the Australian public ascribes to books and the difficulties authors face earning a living delivering that value.”

The dearth of government funding for literature reinforces this statement. Literature is the least funded in grants and initiatives of almost all the arts sectors by the Australia Council for the Arts, the government’s official arts funding and advisory body. In 2020-21, the council gave out just $4.7 million in grant funding to literature — 2.4 per cent of the total funding pool last year, or around half of what literature received in 2014. In contrast, the major performing arts organisations received $120 million in 2020-21.

At a state level, Writing NSW, previously known as the NSW Writers’ Centre, previously received $30 000 a year in devolved funding from Create NSW – the state government’s arts policy and funding body – which it handed out as grant money to finance local writing projects. This funding was “indefinitely suspended” in 2019, with Create NSW stating they would directly provide the funding in future, rather than going through the independent organisation.

“It’s been a great loss for the literature sector, as these grants supported a really diverse range of early career writers and emerging writing organisations that would be unlikely to get funding through the more convoluted Create NSW process,” Writing NSW CEO Jane McCredie told Honi.

Art has always attracted censure from authority, particularly when those outside the dominant power may access, enjoy, and produce it.

Alison Croggon points out in her essay ‘The Campaign to Destroy the Arts’ (2022) that “since [colonisation], many people in Australian public life have made a special virtue of degrading the arts, creating a tradition of anti-intellectualism that starves and mocks the very idea of creativity.” This anti-intellectualism is internalised and naturalised within much Australian culture. Reid tells me that she felt oddly ‘embarrassed’ sitting down to write a novel: “[It] seems so kind of hubristic… like, who do you think you are?”

It is impossible to discuss this crisis in the literary sector without mentioning the broader deprivation of the arts in Australia.

In recent years, consecutive Liberal leaders have eroded arts funding bases, increased job precarity, and, during COVID lockdowns, starved the many freelancers, contract workers, and short-term casuals in the sector of basic financial support. According to the ‘Creativity in Crisis’ (2021) report, spending at federal level on the arts reduced by nearly 20 per cent between 2007 and 2018, with local and state governments least equipped to fund them picking up most of the slack.

Yet some argue there is a particular quality to creative writing which sets it apart from other arts. Perhaps it is because writing is haunted by the spectre of genius. Good writers are born good, the myth says, and will cultivate their skills in private; any investment in writing education or infrastructure is inane. Of course, if applied to any art form – such as dance, playing an instrument, or acting – this belief would seem as absurd as it truly is.

“It’s always interesting that people say that about writing,” says author and Creative Writing degree coordinator at USyd, Belinda Castles. “You would need to learn to be an actor or to play the violin. It’s a combination of various qualities and yes, perhaps talent, but also craft, attentive reading, and practice.”

“To know how to write a good sentence is not just to know how to write a correct one,” says Mark Treddinick, a poet and teacher at the University. “Some truths are not well understood, and not properly spoken for in badly made sentences.”

Treddinick speaks to the value of learning creative writing and literature to practise syntax and style, not just grammatical correctness.

“Does a sentence have the same kind of integrity as that bridge over there or the building that you’re standing within? We need things to stand. Not just to look pretty and not just to be unique, we need them to keep the weather out and not to fall down the heads of other people.”

Last week, the University of Sydney merged the Department of Writing Studies and the Department of English into the discipline of ‘English’, effectively dissolving both departments as part of its 2022 Future FASS proposal. This proposal will see the Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences departmental operating structure reshaped into a disciplinary one; departments long embedded in the University’s history and reputation will be merged and replaced with nebulous ‘disciplines’, which are organised into revised ‘schools’ (i.e. the School of Art, Communication and English and the School of the Humanities). The move has been vehemently opposed by most department chairs for further eroding departmental autonomy in the Faculty, and centralising academic power in the corporate hands of university management.

“There’s no one at a university who doesn’t write,” says Tredinnick. “It always made a lot of sense to have a body of knowledge at a university [the Department of Writing Studies] teaching people within that structure, how to do their core activity,”

Treddinick, who taught casually within the Department of Writing Studies, was not notified of its dissolution until my speaking with him.

“I kept wondering this year, why I haven’t got a contract,” he says. “It’s not been a bother, but it could have been; if I [was] another person, or if this was another year for me, I would’ve missed that income quite radically.”

If we do not invest in our writers, only those with the time, resources, and security to invest in themselves will be able to write. According to the National Arts Participation Survey (2021), “an author’s capacity to earn income from other paid work is boosted by high levels of education” as “they also possess technical skills (the ability to compose, write and edit) that lead to work that does not produce creative output.”

In universities, the accessibility of an arts education has been severely impeded by government cuts and the institutionalisation of corporate management systems. Morrison’s 2021 Job Ready Graduates Package more than doubled the price of arts courses, discouraging students from lower-SES backgrounds to enrol (with some regional universities recently threatening to completely cut their arts programs). The Creativity in Crisis report warns that a combination of higher student debt and unstable, poorly-funded wages in the arts sector may mean “future cultural outputs will increasingly reflect a narrower set of experiences and understandings, further excluding voices from working class, migrant and marginalised communities.”

“Less people have the means to be able to [write] and it certainly doesn’t entice younger, aspiring writers to pursue English degrees if they’re more expensive than science degrees,” says Toby Fitch, poet and lecturer of creative writing at USyd.

Further, workforce casualisation, wage theft, and job cuts plaguing the university sector in recent years have enormously impacted the arts. Last year, 80 casuals in USyd’s arts faculty lodged a wage theft claim for over $2 million dollars, demanding remuneration for six years of unpaid marking and administration work. According to the USyd Casuals Network, this could mean $64 million in university wage theft in the arts faculty alone, if those casuals’ experiences reflect that of the 2455 casuals on the 2021 faculty payroll.

This is despite the University recording a staggering $1.04 billion surplus for the year.

Fitch was denied conversion to a continuing position in 2021 after being a casual creative writing tutor at USyd for six years.

“I was doing more than necessary to be able to apply for a conversion,” he says.

Following his rejection, he opened a dispute with management; when the issue still was not resolved, the National Tertiary Education Union (NTEU) took the matter to the Fair Work Commission. Though management has since capitulated, Fitch says the matter still affects him.

“A lot of stuff is quite triggering around it. I’m still helping out with the Casuals Network and the underpayment campaign against wage theft,” he says.

Belinda Castles corroborates this reality of mass-casualisation in the university arts workforce. “A job like mine, where you work full time, is really difficult to get… to some extent, I put it down to timing and luck, and a lot of my colleagues are having to scrabble together full-on work lives in semester time,” she says.

“They care about writing, so they spend a lot of their own time on student feedback, and time to writers is valuable. It’s always time you could be writing.”

Treddinick adds that asking casuals to spend a prescribed amount of time marking work is asking for students’ education to “suffer”.

“When the system changed to the current system where I have to timesheet all of my hours, and all of my hours are legislated, and I’m meant to be marking 6000 word pieces for 30 minutes [each]… that’s a joke.”

More broadly, a decline in arts funding combined with the pandemic has created a deficit of permanent, well-paid positions throughout the arts sector which writers typically used to supplement their incomes in the past.

“They work for festivals, for events programming, they work for publishers or in publishing… to be nearer the circles in which they want to be part of, but because the whole sector’s not well funded, it’s difficult [in all of those industries],” says Fitch.

He describes working multiple jobs to pay rent while teaching as a casual at USyd: “I was doing all those jobs at once and teaching at university… It was like five casual jobs… I was atomised.”

“All the editors and administrators of arts organisations and literary journals are stretched thin and can’t always hire new people,” he adds. “Although there are lots of people that would wish to have one of those jobs, everyone in those jobs is overworked.”

It is clear financial support for the literary sector is well overdue. The richness that literature and its makers contribute to Australia’s national identity is indispensable, and must be defended in an increasingly corporate educational model.

But students and staff are not powerless in fixing these issues, particularly with the recent change of government. When Albanese announces his National Cultural Policy for Australia later this year, which is currently open for submissions from the arts, entertainment, and culture sectors, let it not value writers below other artists. The qualities of intellectual acuity, empathy, and robust expression that literature teaches are, if nothing else, the forebears of thriving democracy.

“It’s very difficult to kill the arts because it’s what gives us joy in our lives,” says Castles.

Let it not take a pandemic lockdown for a writer to open a word document for the first time and create a novel, award-winning or not.