CW: This article explores themes of sexual assault and harassment, racism and institutional betrayal.

When the results of the first nationally-coordinated survey on student safety were released in 2017, they confirmed what many had long known: that our universities were host to widespread sexual assault and harassment. Subsequent reporting later uncovered a culture of hazing and misogyny in residential colleges, drawing the focus of a growing global movement against rape culture to our campus.

In the time since, the University of Sydney commissioned an investigation into the cultural of its colleges, known as the Broderick Report, committing to fully implementing its recommendations. High school curriculums and, more recently, state legislation recognised affirmative consent. The stories of those who have experienced harassment garnered public attention, platforming and destigmatising conversations around sex and sexual violence.

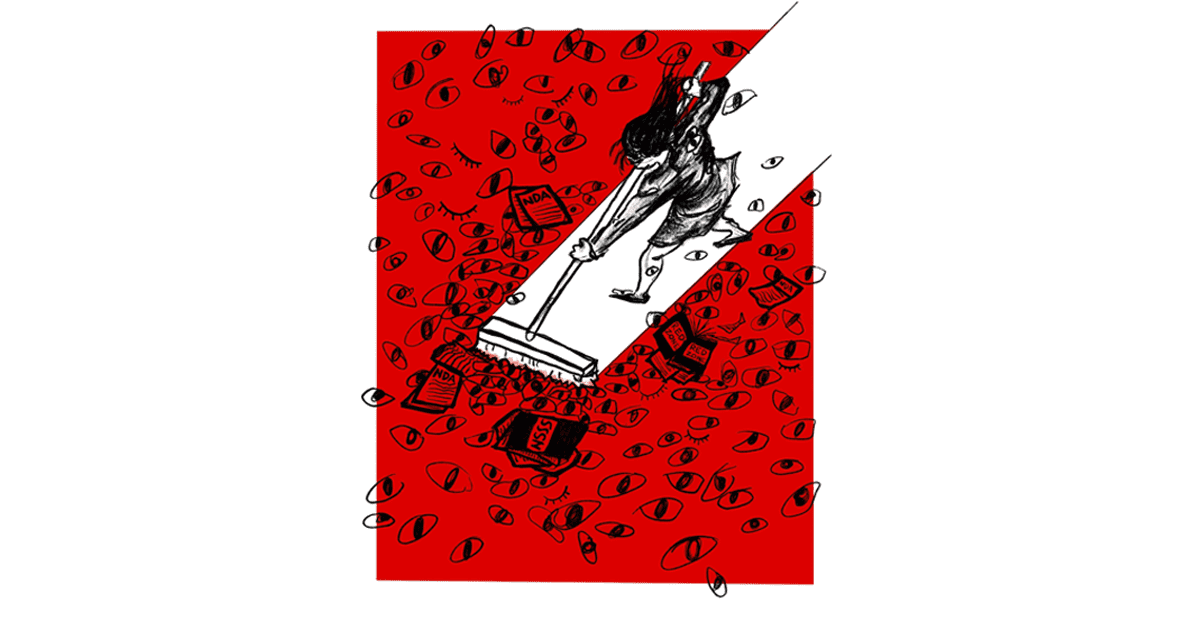

Institutions were, at last, beginning to acknowledge their historical role as wilfully blind bystanders, committing to act on the needs of those who have experienced assault, sometimes referred to as survivors.

Then in March this year, the ANU’s Social Research Centre released the 2021 National Student Safety Survey (NSSS). The findings are clear: Our University had inadequately responded to the sexual violence endemic on campus. Five years on and nothing has appreciably changed. 1 in 6 students, the survey shows, have been sexually harassed since starting university. An even greater proportion of students, more than 1 in 4, report being harassed in their student accommodation.

But how? A module on affirmative consent is a prerequisite for incoming students. The Broderick Report is public, with formal action purportedly being taken by the colleges. Awareness of sexual violence is now, arguably, ubiquitous. Yet the revelation that harassment is still so rife comes as no surprise to student unions, who have long stressed the need for universities to take further action.

In the wake of the most recent NSSS, and with the issue of student safety once again on the agenda, how do we avoid the same mistakes? What do we change when nothing changes?

The limits of consent education and awareness

This question was particularly on the mind of Sachi*, a now-graduated student who left her residential college and transferred universities after experiencing on-going harassment by fellow students.

“I was put into this really high pressure environment and then there was a lot of harassment, not just sexual harassment, but also a lot of racial harassment at times, in classes and socially. And that really was difficult to deal with at the time,” she said.

When Sachi arrived at campus, the results of the first NSSS were already a point of discussion. Like other students, Sachi had to undergo the consent education that had been implemented by many universities as part of their primary prevention. Much of conversation following the 2017 NSSS focused on changing behaviours, to prevent sexual assault and harassment from happening in the first place.

The consent education that Sachi completed, which is still in place, was delivered through a mandatory module; a half-hour course administered online that explains what is expected of students. These courses emphasise an affirmative consent model, wherein consent develops as a conversation, that can be revoked at any time, and sexual partners bear an on-going obligation to check in with one another. The delivery of consent education by universities is central to their rebutting of claims of inadequate action, acting as a reputational safeguard.

However, these modules are passive, non-interactive forms of education: mere box-ticking exercises that students click through without reading or thinking critically about consent.

Naomi Smith is the Sexual Harm and Response Coordinator at the University of Melbourne Student Union (UMSU) — a role established in 2019, two years after the 2017 NSSS. According to her, programs that engage with students’ ability to critically think and show leadership within their communities are more likely to counteract victim blaming and shape attitudes against sexual assault and harassment.

“These can be in-person workshops, which involve them having discussions with peers around difficult topics,” she said.

Some narratives around the need for cultural change can over-simplify the causes of sexual violence, framing the issue primarily as a lack of consent education. However, the persistence of underlying misogynistic behaviour, as evidenced by the 2021 NSSS, calls into question the effectiveness of current consent education in preventing harassment.

“I think that there are a lot of perpetrators who honestly have an awareness of consent … who legitimately don’t really care about the impact they have on others, insofar as they abuse their power to their advantage. And they essentially know they can get away with it,” said USyd SRC Welfare Officer Grace Wallman.

“The University reproduces the sort of social issues that lead to harassment, as well as facilitating elitist cultures in certain parts of the University. These one-off attempts at education fail to develop a holistic intersectional understanding of why consent is important.”

In tandem with consent education, bystander training has been introduced for students in leadership positions as a tertiary intervention against assault, aiming to induce behavioural change in populations and places where misconduct is most prevalent. This is deployed especially at college or society events where bystanders can intervene in potentially harmful situations or coercive dynamics. Students are then encouraged to report any questionable behaviour they observe to peers close by who they can trust.

“A lot of the harassment we experienced was at clubs by fellow students. There was a lot of what my friends call pre-sexual assault, things like groping and intimidating, where you feel violated, but nothing has quite happened yet,” said Sachi.

Education on affirmative consent concerns discrete physical acts done in private, excluding more subtle behaviour or conduct online, which slips under the radar of bystanders. Older students or those with relative power likewise evade accountability, as bystanders are tend to be familiar with those involved and consequently feel social pressure to take their side. Formal, clear, and consistent grievance processes in place to deal with conflicts would better solve this issue — but they largely do not exist at USyd.

For Sachi, the impunity enjoyed by this kind of harassment extended to behaviour in class.

“The issue with racial [harassment] is until someone says something so obviously racist, they [University] don’t do anything about it. This kind of everyday stuff that kind of beats you down bit by bit.”

Activism around improving cultural awareness often comes from student collectives and not the University, resulting in a lack of understanding and acknowledgement of microaggressions by students and staff, whether they be sexist, racist, or homophobic.

“Now I know what is right and wrong, and I am okay to call it out. But then, when someone tells you to not just be sensitive, as a 19-year-old kid, you think, ‘Oh shit, I am being too sensitive.’ And that kind of compounded my own stress and anxiety about my own judgement,” said Sachi.

The burden of reporting

Understandably, the discussion following the 2017 NSSS focused on encouraging awareness and prevention. But as the 2021 NSSS indicated, there is a substantial body of students at university to whom assault has already happened and continues to happen. For them, what now?

Sachi encountered numerous barriers when reporting the harassment she experienced. While on a dating app, an older student sent Sachi unsolicited and detailed rape fantasies.

“I hadn’t known how to deal with it. I was like oh fuck, I don’t want this person after me, so I tried to make it into a joke but he was dead serious about it. He had apparently seen me around… And so he’d seen me walk around and had this whole thing built up. A friend told me to report. And I did report it, but nothing came of it,” she said.

“The general feeling had been that because I’d made a joke of it and I tried to placate him over text, is it really worth following up? The fact that I was uncomfortable and, as a young woman, I didn’t know how to call them out on it, and the fact I initially didn’t, was used against me… I was like… did I deserve to be talked about like that?”

Situations where victims are too uncomfortable to pushback against perpetrators are often miscast and misconstrued as consent. Further, the conduct institutions condone or discipline has a normative influence on young students who are navigating what is acceptable and healthy, and what they ought to push back on.

It is important to remember that students’ experiences navigating care systems and disclosing traumatic events impacts their trust in institutions more broadly. When nothing is done with complaints of misconduct, victims can feel like they’ve overreacted as the University’s judgement ultimately does not align with theirs, and as such, they struggle to trust themselves in understanding what is and is not acceptable.

Sachi also spoke of the futility of reporting abuse from repeat offenders.

“There was one person who, every few weeks there was an allegation against, and they just kept moving him around from room to room within the facilities,” she said.

At the same time, a friend of Sachi was kicked out of the college for subletting her room over the winter break, contrary to her contract, leaving a mark on her rental history, unlike those who had been internally relocated. As the alleged perpetrator remained, students began warning others, however these communication channels were only accessible to students in his physical orbit and visibly interacting with him in public spaces.

“They just kept moving him around. So every few months we would be like, ‘oh no, he’s gone from here to here,’ or ‘something must have happened’. ‘Oh wait, no, he’s here now, oh fuck- we should tell our friends to be careful,” she said.

“It was all kids trying to protect other kids. And it’s not just women, it was the men too. They would talk about it to each other. It was a weird whisper network where everyone was helping, but for some reason the authorities wouldn’t help. It just became like a point of commiseration for everyone, especially in our women of colour group, because everyone knew that everyone else had a story about it. So there would be a lot of sympathy and a lot of love that would come from us. But there was no official avenue that we knew of that we could talk to.”

After experiencing assault, it is not often clear where to go in the first instance. According to the 2021 NSSS, 1 in 2 students do not know the reporting mechanisms or support available to them on campus. There can be multiple points of contact that provide confusing responses and pushback, be it vague requests for more information or a referral elsewhere. When making a report, you may have to re-tell your story multiple times, to friends, to the college and then to university bureaucracy.

For students like Sachi, who lived in off-campus accommodation run by external providers like UniLodge, the complaints process is different. When disclosures are made, either directly through official administrative channels or via understaffed and inadequately trained RAs, they are investigated by a company that has little incentive to act and no power to deliver academic repercussions.

A current issue is that complaints of sexual assault are made through the University Registrar, being the same processes as bullying and academic misconduct claims which are not trauma-informed. If you are assaulted, you suddenly become burdened further by having to navigate this bureaucratic system and a mass of documentation requests, where it may be unclear how they will be involved in the process or on what timeline they will receive a response.

Further, large institutions like colleges, clubs, and societies, are incentivised to not properly address issues, because doing so prolongs the cycle of public scrutiny on their approach to sexual harassment and harassment more generally.

“I think that a lot of them have the incentive to just kind of push this out off the agenda as much as they possibly can, which often looks like only taking very minimal action,” said Wallman.

Colleges with a reputation

Reputational risk, it seems, has not been enough to motivate meaningful change at USyd’s residential colleges, where the cultures are notoriously problematic and frequently feature in the news for hazing and sexism scandals.

Recent litigation may be changing this, however. A former student of John XXIII College at the ANU successfully sued for negligence in 2020, securing over $400,000 in damages, a sum that was slightly reduced on appeal. She had been assaulted by a fellow resident on a night out during a college event. Justice Michael Elkaim held that the College either knew about or condoned the event, and in adopting stances to protect its reputation, had breached its duty of care.

Outside of finding substantial harm had occurred during the College’s mishandling of the complaint, he also found they had been negligent from its “failure to take any steps to prevent the development of a culture within the College of excessive alcohol consumption and subsequent sexual assaults.”

Any precedent of liability for inaction against cultures in Colleges that inadequately prevent assault may be limited to those with the resources to bring legal action and documentation supporting a clear narrative of harm to secure economic damages. However, the prospect of further strategic litigation or class actions may incentivise the colleges to change the cultures they are responsible for fear of legal risk.

The colleges that reside on USyd’s campus are predominantly religious and governed by state legislation. Grievances that are reported go through pastoral staff who are often employed because of their professional or formal religious affiliation. Religious institutions are notorious for institutional sexual violence, merely the perception of which can influence the likelihood that a student will disclose or seek support while religious staff in housing are responsible for student safety.

This logic forms part of the ‘abolish the colleges’ campaign by the SRC collectives, calling for a repeal of legislation that governs the Colleges in favour of affordable housing and a public body or Minister for Housing becoming responsible for them. If someone does not feel safe in university accommodation, having affordable student housing that is safe and well-monitored can make a big difference.

A search for support

Students encounter confusing and decentralised systems when seeking support. During what ended up being her final semester at college, Sachi found herself in a depressive state, no longer going to class or handing in assignments, developing a dependency on alcohol and ultimately being placed on academic probation. The waiting times for university counselling made psychological support inaccessible.

“It was really difficult to really navigate the processes at the time, especially as a young kid. I think if I was thrown into that situation now, in my twenties, I would be a lot more confident about where to go, what to do,” she said.

“But that guidance isn’t really given to students. We were children, we were teenagers, you know, so to throw us into the deep end like that and to not have proper systems in place… Looking back at it there was a lot of shame around it, but it wasn’t really our fault.”

One of the most significant takeaways of the NSSS is the extent to which having an incident can deteriorate a student’s mental health. Sachi had moved interstate to pursue tertiary studies, leaving her far from home and from her primary support networks. She had no access to mental health services at the time, as most of her money went to paying rent to live in student accommodation close to campus.

“Any sort of mental health, any help at the time, any sort of authority taking seriously what was going on, not just to me, but to others who could back up what had happened or who have similar experiences, would’ve helped so much.”

The Student Counselling Service at USyd is limited to six free sessions a year, meaning that those who have experienced sexual assault or harrassment may not be able to access the amount of support they need through the University, according to Wallman.

“In the broader community, waiting lists for psychologists are extremely long. If you are in a position where you need crisis support, and support in the intermediate term, the University really doesn’t have much to offer you.”

Academic purgatory

Following an assault, a student can find themselves concurrently navigating reporting an incident, securing support and appealing against academic probation. This was the case for Sachi.

“I was basically catatonic and I hadn’t left my room in about three weeks. And so many people tried to reach out. I remember there were a few friends who knocked at the door and I heard the knock, but I was so out of it that I couldn’t even get out of bed to answer. I was at the level where I was truly one jump away. My parents got on the first flight to bring me home. I left all of my stuff there and my world shrank to my family’s house when I returned. It was then that I received a letter basically saying I had failed,” she said.

If the census date has passed, students have to go through the bureaucracy of special considerations or discontinue without fail, which have narrow and arbitrary time windows, meaning these are only exerciseable if students can secure documentation before the option expires. The burden falls on survivors to develop resilience themselves, expected to navigate these processes just as they experience one of the most stressful periods of their lives.

This environment has been exacerbated by the Job-ready Graduates Package passed in 2020, which brought back the subject withdrawal date and punitively removed access to HECS for students with a completion rate of less than half of their coursework in an academic year. The University took no public stance against the legislation.

For students to comfortably continue their degrees, special considerations and restrictions on degree progression need to be reformed. Even changes as simple as content warnings can make units more accessible, allowing students to remain enrolled. Informing students of when they may be exposed to potentially re-traumatising material and providing alternatives for assessment, especially when they do not have a choice of stepping away, may seem small but can be the difference between being able to take a course or not, and this, on an individual level, can be really impactful.

Resistance to reform rests on the belief that relaxed accommodations would be abused by students with vexatious claims, faking or overstating an illness or misadventure, and eroding the University’s capacity to produce employable, time-managing graduates. This fails to consider that modern workplaces are not inflexible, and that same-day GPs who sign off on validating documentation are also in a position of believing students, who they are sometimes seeing for the first time, relying on their accounts of their symptoms or history. A higher bureaucratic burden then does not serve as an effective filter preventing exploitation, at least not to the extent that justifies prejudicing those unable to find and acquire professional paperwork quickly.

That being said, there have been small improvements, including recent changes to special considerations at USyd where documentation is no longer required for extensions of less than 5 days. This is a result of advocacy by the SRC.

Safer Communities

The establishment of the Safer Communities Offices (SCO) at various universities, including USyd in 2019, has been the most substantial response to the NSSS results. Embedded within universities’ structure, these Offices centralise response and support systems, dealing not just specifically with sexual assault, but also with domestic violence, bullying and harassment.

“Safer Communities centralises the bureaucratic burdens and provides students with initial discussions and emotional support. Here, referrals are made to academic adjustments or psychological services, however this often takes the form of a letter of support. The labour of applying still sits on students,” she said.

For students who have experienced assault, the SCO at USyd often refers them to the RPA Sexual Assault Counselling. SCOs are close to best practice, according to Smith, but at UniMelb they lack a physical space for survivors. At USyd, the SCO has have a physical space on Level 5 in the Jane Foss Russell Building, however this is not advertised or clear on its website. This limits their therapeutic potential for vulnerable students and limits awareness of SCOs as a supposedly centralised service.

“If you’re going to a counselling office, there’s usually an office in a waiting room and a space that you can be in and feel safe in. We feel like that’s lacking on our campus,” said Smith.

According to Smith, SCOs are under-resourced and lack sufficient trauma-informed training specific to disclosures of sexual assault. In order for outreach and community development to become culturally-aware and effective, it is imperative that the employment of staff reflects the diversity of the student population.

For Smith, SCOs should be accompanied by a full-time role such as UMSU’s Sexual Harm and Response Coordinator, which she occupies.

“University administrations take advantage of the fact there is going to be a changeover of reps every year, where conversations and advocacy can progress over a year, and then backtrack or stall,” she said.

The establishment of a full-time coordinator within UMSU has avoided this in some way. It has enabled the student union to train incoming activists, sustain pressure and compile students’ experiences with administrative processes. This allows them to build an evidence base that validates student voices, useful when speaking to University administration who have warped perspectives about what is valid.

For Dashie Prasad, the USyd SRC Women’s Officer, the fact the service sits within the University itself rather than its student union is problematic. According to them, the extent to which SCOs are willing to engage in education and bring attention to the prevalence of harassment on campus is restricted while ever it poses a reputational risk to the University. This means students’ experiences are not being collected and advocated, particularly as the evidence suggests these services are inadequate and require change.

“Inherently, I think survivor-centric care is not something the University can provide because the priority for the University is its policies, its insurance and making sure it legally is protected. There is an easy solution, let the student union do it,” they said.

Where next for activism?

The National Union of Students (NUS) is encouraging student unions to join its upcoming ‘Our Turn’ campaign, where universities are given a report card on their progress in adopting the NUS best practice recommendations for harassment reporting and support. The campaign attempts to shame universities into action, seeking capitulation by appealing to universities’ sensitivity to reputational and financial harm.

Yet the onus to ‘mark’ the report cards of each university is placed on each campus’ student union, attracting criticism from student activists for the work it places on them.

According to Prasad, the ‘Our Turn’ campaign would require the student union to “audit the University, services and supports for sexual violence survivors, which are already disparate and difficult to understand.”

The end result would impose demanding and complex work on student activists, which, according to Prasad, would not be an “effective use of their time.”

If student unions do decide to take the initiative up, ‘Our Turn’ could succeed in keeping sexual assault on campuses at the forefront of universities’ agendas.

“It’s very easy to get caught up in a cycle of just moving on to what feels like the next prominent issue, and [sexual assault] kind of just sort of falls off the agenda. I think that’s really the main thing that we need to combat. Sustaining pressure is vital to incentivising universities or residential spaces to take action to ensure student safety.” said Wallman.

Going forward

To properly respond to the issue of sexual violence on campus requires an assessment of the nature and extent of the problem at USyd. In response to the 2021 NSSS, the University released only a summary of statistics specific to their campus in the form of an infographic.

“The University is really keen to wash their hands of any responsibility around sexual violence to their students. I think that’s reflective of them not wanting to share the entirety of the data that has come out of the NSSS,” said Prasad.

The University of Sydney proudly invests significant resources into elite athlete and academic development programs, selling itself on the role as playing a front-seat role empowering its students to succeed. However, it has not adequately adopted or responded to key welfare demands that would empower those who have experienced assault and harassment. As it stands, the they cannot both take credit for empowering its students when they want to, and avoid accountability when they don’t. Through this abdication of care, the University misses an opportunity to lead on cultural renewal and be proud of playing a positive role in the lives of all students, irrespective of their immediate value to the institution.

Sachi has since graduated. She looks back on her experiences at the University poorly.

“I haven’t returned, and I find it too hard to reach out to the friends I made there, many who also went through similar stuff.”

For students who go on to graduate, they do so in spite of what happened to them and in spite of a lack of support. When the University tries to take credit for their successes, it is both dishonest and unjust. For students’ experiences with assault and harassment to change, the University must also change.

* denotes a pseudonym to protect the interviewee’s identity.

Students seeking support can find resources at USyd’s Safer Communities Office or contact a caseworker from the USyd SRC. Students are also encouraged to contact the Royal Prince Alfred Sexual Assault Service or call 1800RESPECT on 1800 737 732.

Update: This article was amended to include the whereabouts of the SCO Office at USyd in Jane Foss Russell Building and updated the name of the Student Counselling Service, formerly known as CAPS.