Drawing from the extensive collection of the University Archives, the Quad may have looked very differently had history taken a different turn, with five alternative visions for the Carillon Tower and a forgotten blueprint for its iconic facade.

Crown steeple and an elongated Quadrangle

It is hard to imagine an alternative to what stands before University Avenue as one ascends from the Victoria Park Steps — USyd’s iconic Quadrangle dressed in Sydney sandstone. Yet the institution’s imposing facade may have seen a very different future had the University proceeded with a different vision for Fisher Library.

In 1890, a plan was drawn up where the Carillon Bell Tower would have been accompanied by an enormous, elaborate crown steeple soaring high directly behind it. This structure was one of the first iterations of Fisher Library following a £32,000 bequest from Thomas Fisher’s estate, the equivalent of over $3.5 million today. Situated just below the crown tower, this Fisher Library was to house a large, airy chamber resembling a rotunda. The rotunda separated USyd’s Carillon Room and the Anderson Fellow’s room and would have occupied two floors above the Quadrangle’s main entrance, protruding into the Quad by a substantial degree.

The crown chosen for the 1890’s design is likely an imperial crown, similar to the ones at King’s College in Aberdeen and St Giles’ Kirk in Edinburgh. At King’s College, such a crown tower represented claims to “universal dominion” rather than a mere royal connection. For USyd architectural historian Professor Andrew Leach, the early, elaborate plans for Fisher Library is evident of an institution seeking to project itself as a bastion of moral authority and cement its place within the British empire. Despite USyd’s roots in Benthamite secularism, the influence of the High Anglicans and Protestants among its founding professors was indelible.

“Neo-Gothic architecture was one of the languages used by institutions with a moral underpinnings that universities were supposed to have, a Gothic building suggests what your moral mission is about,” Professor Leach told Honi. “It was conceived of as a British building in Gadigal Country.”

In this lens, USyd’s plan for a crown steeple, had the University Senate opted for this option, would have further entrenched the institution’s reputation as a symbol for Britain’s invasion of Australia, exacerbating an already violent relationship between Sydney University and Gadigal Land.

Another feature that was abandoned was a double cloister that would have clothed USyd’s Quadrangle. The blueprint would have seen two internal arcades dressed with Corinthian columns in a classical Italianate style reminiscent of Italy’s older universities like Padua.

Another change in this blueprint was an extension to the building’s facade beyond the Great Hall, featuring an ornate Tudor arch and a second lead spire to rival the Carillon Tower where the MacLeay Museum lies today. Adjacent to Nicholson was a dramatically different look for the now-dormant Nicholson Museum, in what resembles an ecclesiastical Chapter House, originally planned to be just behind the Great Hall where the Vice-Chancellor’s office now resides.

However, all was not lost with an early prototype of MacCleay Museum clearly visible in the Western elevation (or the back of the Quad). Here, the early MacCleay Museum, identical in structure to what was eventually realised, features a double height gallery surrounded by two floors reserved for specimen displays. However, in contrast with 1890’s blueprint, MacCleay was built not in the Perpendicular sandstone of its early design, but rather, expressed in Romanesque redbricks instead.

Little is known about why the plan fell through. However, USyd ultimately commissioned NSW Government Architect Walter Liberty Vernon, together with William Mitchell and George McRae to build the Nicholson Museum and old Fisher Library in their current incarnation.

Five visions of the Tower

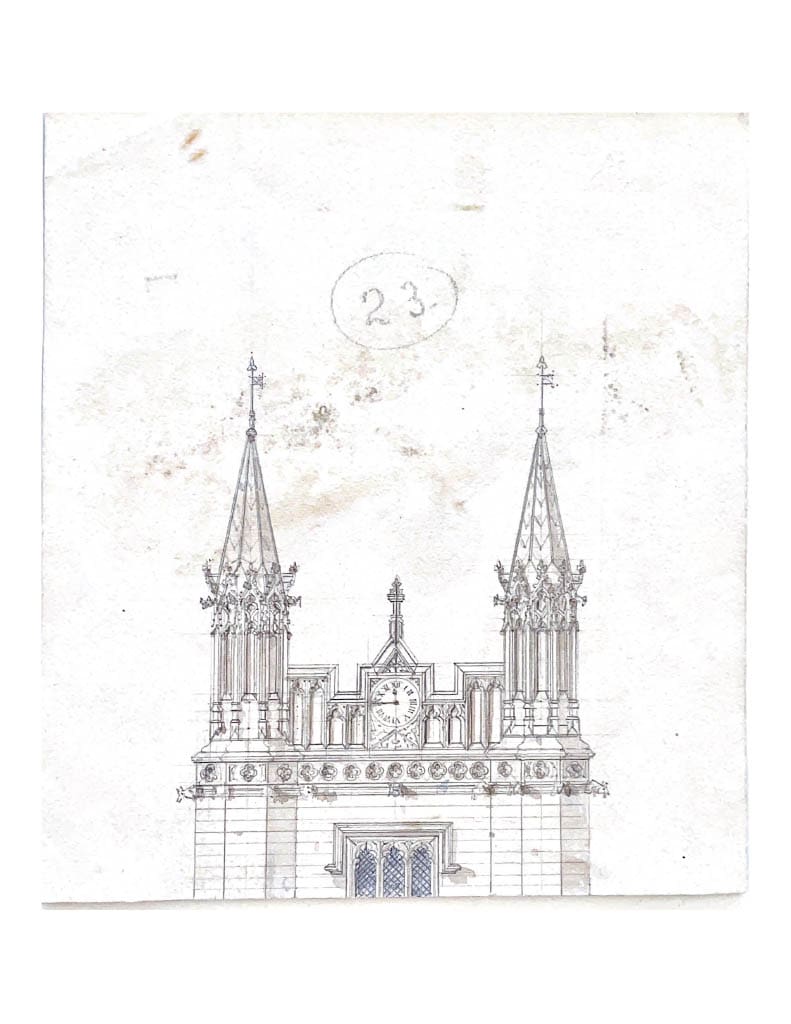

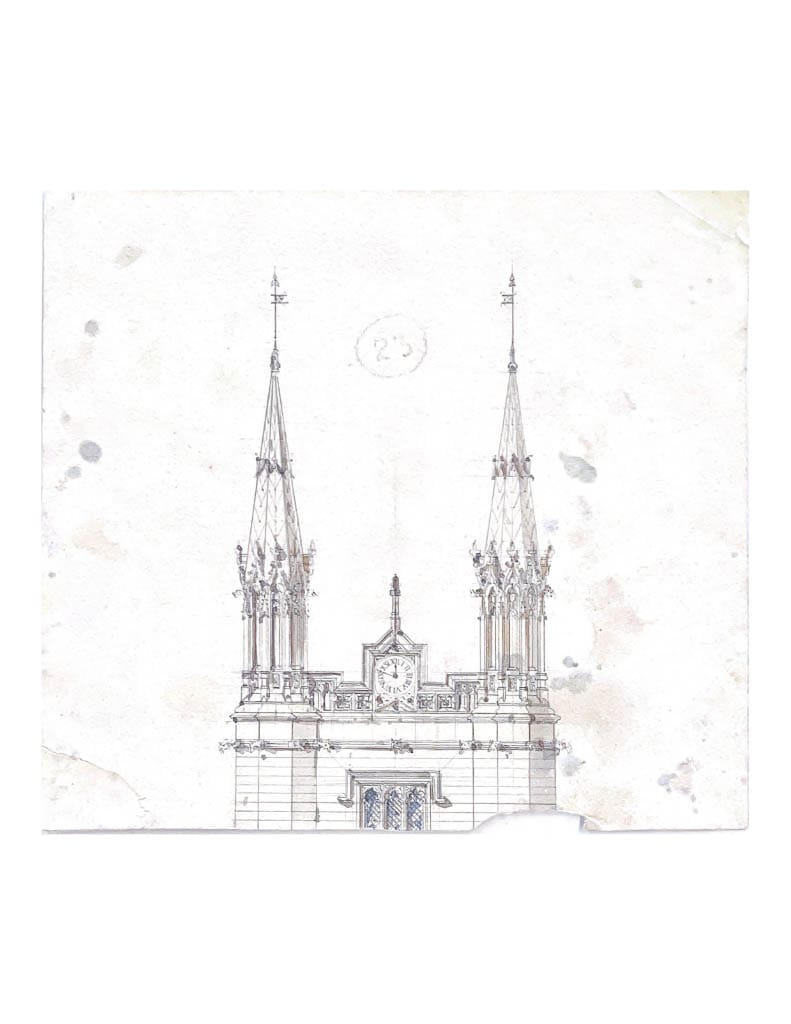

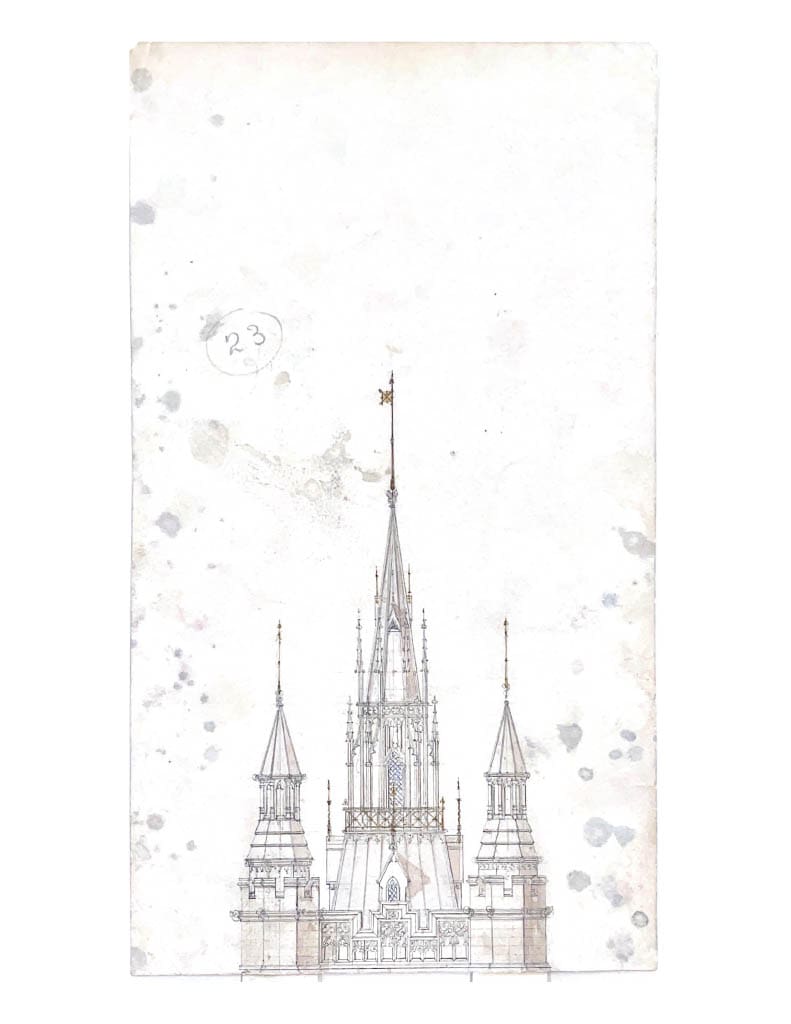

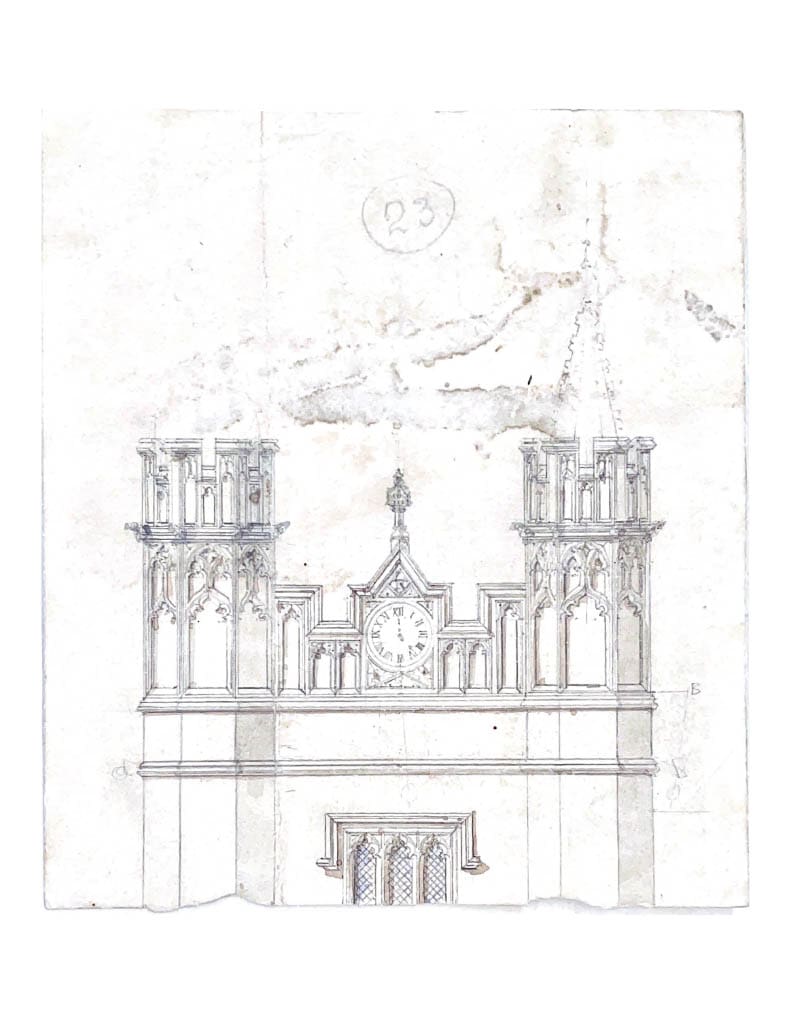

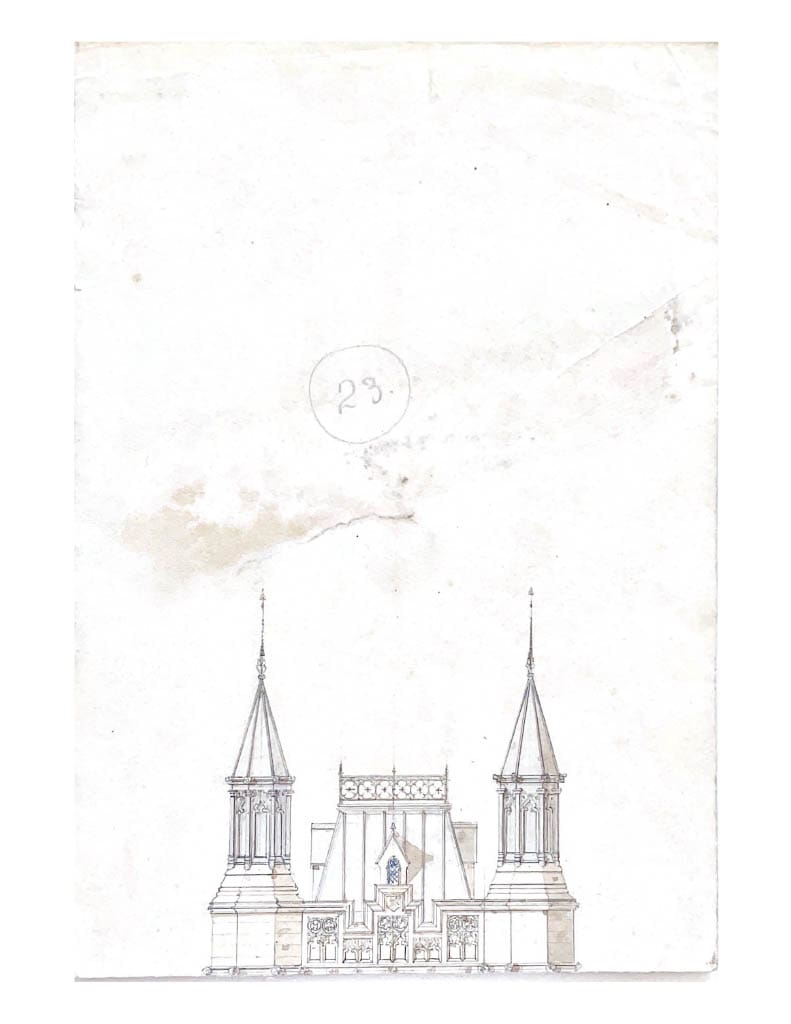

Had things turned another way, the Carillon Tower may have been very different to its current form. Endowed with one of Australia’s only Carillons together with Canberra and Bathurst, it has played a role in greeting countless new students and congratulating graduates. Prior to construction, colonial architect Edmund Blacket designed five other versions of the structure, ranging from more austere yet playful plans to vastly more ornate designs.

One of the designs would have seen the Tower soaring with a set of crocketed sandstone pillars, featuring curled leaves motifs, adorned with a lead-cladded spire. Not to be beaten, another drawing witnessed the Quad being topped with a series of pinnacles atop a fancy Mansard roof and embellished with a miniscule gold-gilded flag at its peak.

Among the simpler designs was a Tower topped with a leaded Mansard roof, somewhat echoing what was built for Otago University’s Registry Building. A similar drawing shows a series of decorative crenellated battlements, eschewing spires altogether, putting the Quad on par with the romantic architecture of Scotland’s castles. As for Professor Leach, these two plans were his firm favourites due to his affinity for Scottish baronial architecture which was reflected in these seemingly pared down, “playful” yet striking designs.

“I just have a bit of a sucker for Scottish Baronialism so that’s my reason there, there’s a kind of playful addition, just because it seems so ridiculous. For me, it’s a toss up between the Disney princess tower and the Mansard [roof], both of which would have been silly but also made them fun!” Professor Leach declared.

A radically different Physics Building

Gorrie McLeish Blair and Vernon’s design for the Physics Department where the Brennan MacCallum Building is today. Plan courtesy of the University of Sydney Archives.

Also abandoned was a plan for a Neo-Gothic vision for USyd’s Physics Building. Had the University realised the plan, designed by NSW Government Principal Designing Architect Gorrie McLeish Blair in 1917 under Walter Vernon’s tutelage — famed for the Mitchell Library and Sydney’s Central Station — Manning Road would have looked very different. Under Blair and Vernon’s masterplan, Physics would have been located directly behind the Quad where the MacCallum Building sits today.

In Leach’s view, the pair’s plans, though “extraordinary” in scale, were not “aspirational” in terms of its outlook, being intended to complement the older Fisher Library’s style as a continuous, harmonious complex. Under the design, a grand entrance, flanked by two massive towers, would have greeted students and professors where the MacCallum Learning Hub currently stands. The gothic edifice was designed to house three departments: Organic, Inorganic Chemistry and Physics alongside a small extension for the Arts.

The building formed what was Vernon’s science complex, who laid out a masterplan for USyd’s science precinct. The plans, Leach observes, were abandoned when Professor Leslie Wilkinson was appointed University Architect one year later in 1918.

“The interesting thing around Wilkinson’s appointment is that in 1917, they’re [USyd] already interviewing for that position,” Leach said, 1917 being the same year of Blair and Vernon’s plan. “When the Chair [of Architecture] was being sought, all of the search and discussions happened in London.”

“So I think it [Blair and Vernon’s plans] was a victim of the ambitions of Wilkinson’s which is not necessarily a bad thing!”

Indeed, Leach praises what Wilkinson and Keith Harris designed for the Physics Building in 1926, in opting for a simpler Italian Renaissance style as opposed to the aged Neo-Gothic already taken up by the Quad. For him, Wilkinson’s Italianate style offered a far more refreshing campus than repeating the Perpendicular Gothic of bygone years.

“The earlier generation built so that we can be seen everywhere, the Fisher Library is about visibility everywhere whereas Wilkinson would like to be low to the ground as long as we’re able to see along an axis,” said Leach, referring to what is popularly known as the Wilkinson Axis together with the Edward Ford Building, also a brainchild of Wilkinson.

“I think the Physics Building is one of the best buildings of that generation on campus. It’s beautiful.”

The future of campus design

It is hard to fathom that, up until the 1950s, USyd appointed its own University Architect, worlds away from the multifactorial and complex job of the modern architect’s brief. Today, much of that work is collaborative, with architects embodied as firms rather than being linked to a specific individual.

Following its 2032 Strategy, USyd will be embarking on a grand development exceeding what it built for Darlington. Just in Parramatta and Westmead alone, developments to match an extra 25,000 students and 2,500 staff is being planned for 2055. This means that a University exceeding 100,000 students is a very real possibility in the next decade.

Earlier this year, Roisin Murphy narrated the history of Darlington’s fierce resistance to USyd’s post-1957 expansion scheme in response to the destruction of community and heritage as part of USyd’s extension. The architecture of USyd’s expansion plans would be wise to learn from the lessons of its past campus designers. Development at any cost, particularly in the context where the sheer scale of its present campus structurally contributes to the atomisation of student life, with each being left to ferociously compete for the limelight, and to fend for themselves among 75,000 others in USyd’s endless pursuit of employability and reductive rankings.

What the abandoned and eventually realised blueprints that ultimately constitutes USyd’s physical campus shows, then, is that its physical infrastructure is equally affected by how the institution itself and governments articulate higher education. Where the romanticism of the 19th century reserved knowledge for a privileged elite and the Brutalism of the 1960’s paved the way for a radicalised generation of students, the next chapter awaits to be written.

History has plenty to impart, inform and teach how campus should evolve in the future, USyd would be wise to heed them.