Content warning: suicide and sexual abuse.

Joey was just three months old when he landed on Australian soil for the first time in 1975. The young family – consisting of Joey, his parents, sister and two brothers – left Tonga for the land of opportunity, at a time when Gough Whitlam’s Labor Government had recently implemented sweeping immigration reforms.

By this point, the racist White Australia Policy had effectively been dismantled, and the long-overdue Racial Discrimination Act 1975 had just been passed. Migrants faced fewer barriers to entry due to the colour of their skin, and the foundations for Australia’s multicultural society were well and truly established.

“Like any other migrant,” says Joey, “we came for a better life.”

When Joey’s family first set foot on Australian soil in 1975, they did so with optimism, with hope. They simply could not have begun to imagine that, 48 years later, their son would be sitting in a cell, detained without conviction, and facing deportation to a country he hadn’t visited since he was a child.

They simply could not have begun to imagine that, 48 years later, their son would be sitting in a cell, detained without conviction, and facing deportation to a country he hadn’t visited since he was a child.

Today, Joey speaks to me from his cell in Melbourne Immigration Transit Accommodation (MITA), where he has been locked up for the last 18 months.

“It’s worse than prison in here,” he says. “This place is designed to break you.”

A little more than 650 kilometres away, deep in the heart of Western Sydney, sits Villawood Immigration Detention Centre – Australia’s most populated facility, with 498 detainees.

Ahmed* spent four years and eight months inside Villawood – an experience he says changed him irreversibly, even five years after his release. Ahmed fled armed conflict in Sudan in 2012, arriving at Sydney Airport in June that year. From there, he was immediately transferred by the Australian Border Force to Villawood.

Ahmed’s voice begins to waver slightly when I ask him about life inside the detention centre.

Ahmed’s voice begins to waver slightly when I ask him about life inside the detention centre.

“It’s inhumane,” he says. “A terrible, terrible place. I never thought Australia could be like this.”

Ahmed is vague at first, hesitant to reveal specific details due to fear of being identified. Ahmed suffers from extreme anxiety that developed during his time in Villawood – perhaps this explains his cautiousness. Only when I reiterate that he will remain anonymous does Ahmed begin to speak more freely, until it all comes out in a feverish stream of consciousness, as if the words are escaping from his lips for the first time.

“The guards, they hate refugees and they enjoy punishing you. They treat you like animals.

“They clearly tell you that you are just a number, not a human,” he says.

The guards Ahmed is referring to are employees of private contractor Serco. In conjunction with the Australian Border Force, both Villawood and MITA are run by Serco as part of their multibillion-dollar contract with the Australian government to manage on- and offshore detention centres.

“When they want to be violent, the guards just turn the security cameras off. They jump on you—six or seven guards at once—they jump on you.

“Then, after, they say self-defence,” says Ahmed.

“When they want to be violent, the guards just turn the security cameras off. They jump on you—six or seven guards at once—they jump on you.”

Ahmed describes one incident where a detainee was attacked by several guards, two of whom pinned him to the ground, with his arm forcibly held behind his back and his face against the concrete. The detainee yelled out in pain, pleading with them to stop because he thought his arm was broken. The guards took no notice, and a Serco manager responded to the detainee, “don’t worry mate, we’ll fix your arm for you.”

Ahmed explains that guards discriminate against detainees on the basis of their race – a clear contravention of Serco’s contract with the Australian government.

“Islander guards look after their own Islander boys, Lebanese guards look after Lebanese boys. There’s not a lot of African guards, so of course, Africans are going to be the victims,” says Ahmed.

Ahmed also alleges that guards engage in sexual relationships with detainees.

“The guards, they use their power to have sex with refugees. They’re not forcing you, but they’re giving you hope. They’re using you and taking advantage of you.

“The guards, they use their power to have sex with refugees. They’re not forcing you, but they’re giving you hope. They’re using you and taking advantage of you.”

“Male guards will abuse their power to have ‘relationships’ with female detainees. The poor girls might think they’re in love with the guards, but the guards are just using them.”

In addition to taking advantage of detainees for sex, Ahmed claims that Serco guards smuggle drugs into Villawood.

“It’s worse than on the street; you can get any drug you want,” he says.

Ahmed’s experiences corroborate the findings of a report by The Guardian, which estimates that $10,000 of drugs – including methamphetamine, heroin and cocaine – are smuggled and sold inside Villawood every week.

For Ahmed, Serco guards have blood on their hands.

“Do you know how many people kill themselves? How many people they mentally torture?”

There were 194 reported incidents of self harm across Australia’s onshore detention centres in 2021, with 67 occurring at Villawood and 42 occurring at MITA.

The high rates of self harm in detention centres are unsurprising to Joey, who also reports violence, racial discrimination, drug smuggling, and sexual abuse on the part of Serco guards.

“I’ve been told that sex happens between male guards and female detainees, and that guards bring drugs in for them in return,” he says.

“I’ve been told by women that they’ve been sexually abused by guards.”

Even in so-called ‘consensual’ relationships, the capacity for a detainee to consent in such a dynamic has been questioned in psychological studies, as the inherent power imbalance lends itself to coercion.

“In other instances, when the guards don’t get what they want, they threaten to send you to Christmas Island, to make life difficult for you,” Joey says.

“In other instances, when the guards don’t get what they want, they threaten to send you to Christmas Island, to make life difficult for you.”

For Joey, mistreatment by guards – most of whom are “bullies” – is just one factor contributing to poor mental health in detention. Indeed, Joey believes that mental health services in MITA are simply inadequate, and far worse than those offered in prison.

Medical services in detention centres are provided by private contractor International Health and Medical Services (IHMS).

“In prison, any medical issue you have is addressed. You have doctors, psychologists, and you get counselling support. You have a whole program dedicated to Christian ministry and support groups.”

By contrast, those in MITA are largely left to fend for themselves. In the 18 months he has spent in custody, Joey has witnessed the mental degradation of countless detainees.

“There’s a lot of broken people in here. Some of them are – and I hate to use the word – but they’re zombies. This joint has destroyed them,” he says.

One particular incident stands out to Joey as a damning example of the lack of care exercised by detention centre staff and IHMS. Joey had been in MITA for just four months when a man attempted to commit suicide in front of him.

Joey had been in MITA for just four months when a man attempted to commit suicide in front of him.

The man, an African refugee whose visa had been terminated by the Australian government, tried to hang himself with a bedsheet in the detention centre’s laundry room. The man had constructed a noose out of the sheet and was in the process of hoisting it to the ceiling when Joey walked in.

Joey managed to talk him out of it.

“I told him that no good would come of it, for him and for his family,” Joey says.

Joey immediately reported the incident to staff, who were unresponsive.

“They told me: ‘Fill out this form and someone from the mental health department will address the issue in three or four days’.

“They told me: ‘Fill out this form and someone from the mental health department will address the issue in three or four days’.

“If you’re going to kill yourself, you can’t wait three days,” says Joey.

Less than a week later, that same man climbed on top of the laundry building’s roof and threatened to jump off and break his neck. After a long standoff, the police were called, and the man has since been placed on sedative medication administered by depot injection.

“Now he walks around lifelessly, his mouth open and drool coming out,” says Joey.

Beyond mental health services, the overall living conditions in detention are, in some ways, much worse than those in prison. Prisoners in Australia generally get their own cell, but in immigration detention, there are a minimum of two detainees per room, and sometimes up to four. In instances of overcrowding, detainees are sometimes made to sleep on mattresses in common areas for extended periods of time.

“When you share a cell with another detainee, your space is immediately halved,” says Joey.

According to Joey, the impact of another cellmate is exacerbated by a lack of available cleaning products.

“In prison, it’s easy to keep your cell spotless. Here, it’s very hard to keep your cell and yourself clean – you just don’t get those cleaning utilities here,” he says.

In comparison to detention, prison places far greater emphasis on rehabilitation. In prisons across Australia, inmates can complete educational and vocational training courses with real-world applications to be used upon their release, such as hospitality and trades courses.

By contrast, such courses in immigration detention explicitly come without formal qualification, meaning they are not officially recognised and have limited application in Australian society.

“In prison you can do courses that will help you. Here, at the bottom of the certificate it says this certificate cannot be used outside. So what’s the point? You’re just wasting your money,” Joey says.

While approximately 80 per cent of Australian prisons are publicly-run, immigration detention centres are almost entirely operated by private companies like Serco. This has not always been the case. It was only in 1998 that John Howard’s Liberal-National government made the switch from publicly-run immigration systems to privatisation, likely with the intention of cutting costs and improving efficiency. Today, immigration detention costs the Australian public a monumental $428,542 per year per detainee, while conditions inside continue to worsen.

A 2017 United Nations report concluded that outsourcing immigration detention to private companies carries great risk of human rights violations. The report found that the profit-making incentives of private companies override considerations of human rights, as detainees have their rights infringed upon with little oversight, effectively granting companies impunity.

The report found that the profit-making incentives of private companies override considerations of human rights, as detainees have their rights infringed upon with little oversight, effectively granting companies impunity.

Companies like Serco and IHMS have limited commercial incentive to create liveable conditions for detainees and promote rehabilitation. Rather, shareholder pressures and the need to consistently turn a profit inevitably encourage cost-cutting at the expense of adequate care.

An analysis of the Serco-run Kilmarnock prison in Scotland studied the impact of cost-saving measures. Here, researchers observed that staff shortages, inadequate training, and a reduction in recreational and vocational services for detainees were associated with increased instances of violence and suicide.

At MITA, Joey reports that staff make no efforts to prevent violence between detainees, which occurs frequently. Just weeks ago at MITA, two detainees who were previously involved in a violent altercation were placed by staff in the same unit. Naturally, another fight broke out.

According to Joey, a managing Border Force staff member at MITA told him: “I don’t care if you guys kill each other, just don’t touch my staff.”

According to Joey, a managing Border Force staff member at MITA told him: “I don’t care if you guys kill each other, just don’t touch my staff.”

“That would never, ever happen in prison,” Joey says.

Joey’s knowledge of prison comes from an eight-year stint following a robbery conviction. Speaking to Joey on the phone, you would never expect that he had ever faced criminal charges, let alone committed violence.

Joey exudes wisdom and calmness, and his voice is heavy with empathy for the suffering detainees around him. For Joey, his time in prison completely changed his outlook on life, and he considers himself completely rehabilitated. It was in prison that Joey started practising Christianity and actively participating in Ministry services, as well as running counselling sessions for fellow inmates.

“In a way, the eight years in prison saved my life. I’m not the person I was 10 years ago,” he says.

Today, Joey uses Zoom to give talks about faith, rehabilitation, and youth justice in drug rehab centres, high schools, and youth groups, and is in contact with a school in New Zealand about an up-coming talk.

Joey was born in Tonga, meaning he retained his Tongan citizenship upon migrating to Australia when he was just three months old. Joey lived in Australia on a permanent residency visa for 41 years, but his visa was cancelled in 2016 following his criminal conviction by then-Minister for Immigration Scott Morrison.

Section 501 of the Migration Act 1958 mandates visa cancellations for non-citizens who are sentenced to more than 12 months in prison. It also provides the Minister for Immigration the discretion to cancel the visas of non-citizens who fail a “character test”, in which regard can be had to less serious criminal conduct and even non-criminal “general conduct”. Individuals who have had their visas cancelled under this section are colloquially referred to as 501s.

Typically, non-citizens who are denied the right to a visa are deported to their country of citizenship. Today, Joey awaits the outcome of a High Court appeal against his visa cancellation to see whether or not he will face deportation to Tonga – a place where he has no ties, no family, and has not visited since he was a child.

If Joey’s family had migrated to Australia three months earlier, he would have automatically acquired Australian citizenship when he turned 10, and today would be out in the community, living as a free man. Instead, the three months Joey lived in Tonga as an infant have condemned him to detention in MITA for the foreseeable future.

The three months Joey lived in Tonga as an infant have condemned him to detention in MITA for the foreseeable future.

Yet just last week, Joey informed me that members of the Tongan embassy have indicated their government will accept no further deportees without additional funding from the Australian government. If Joey’s appeal to the High Court is unsuccessful then, his detention in MITA remains indefinite, along with hundreds of other detainees who cannot be deported to their country of origin.

Having served the full extent of his 8-year prison sentence and now having spent 18 months in MITA, Joey feels that 501s are subject to “double jeopardy”.

“I’ve served my time. I’ve paid my debt to society. Now it feels like I’ve been handed a life sentence,” Joey says.

“I’ve served my time. I’ve paid my debt to society. Now it feels like I’ve been handed a life sentence.”

The current policy of mandatory visa cancellation was legislated by Tony Abbot’s Liberal-National government in December 2014, causing a spike in cancellations from 76 in 2013-14 to 1,278 in 2016-17.

According to Joey, many 501s in MITA had their visas cancelled on the discretion of the Immigration Minister following non-serious criminal offences, such as traffic offences or receiving stolen property.

“The idea that only people who spend more than 12 months in jail have their visa cancelled is garbage.

“There are people in here who had their visas cancelled after a few months in prison, and now face being locked up for years.

“501s are human beings like everyone else, but to the government, our lives are worth less. We’re treated like trash.

“Australians are quick to criticise other countries for human rights abuses. We’re quick to criticise countries like China, Afghanistan and Iran. But it’s happening right here, in our own backyards,” Joey says.

Joey has 11 children and three grandchildren living in Australia who he is not able to see outside of strict visitation hours. He is yet to meet one of his grandchildren.

“We’ve all made mistakes, but all we ask for is one chance. Let us get back to society,” Joey says.

“I’m happy to sign on in the police station every day. I would be happy to put on an anklet where I’m monitored.

“I just want to return to my children, my grandchildren, and contribute to society,” he says.

“I just want to return to my children, my grandchildren, and contribute to society,” he says.

After speaking with Joey for some time, I ask him if he still has hope for the future.

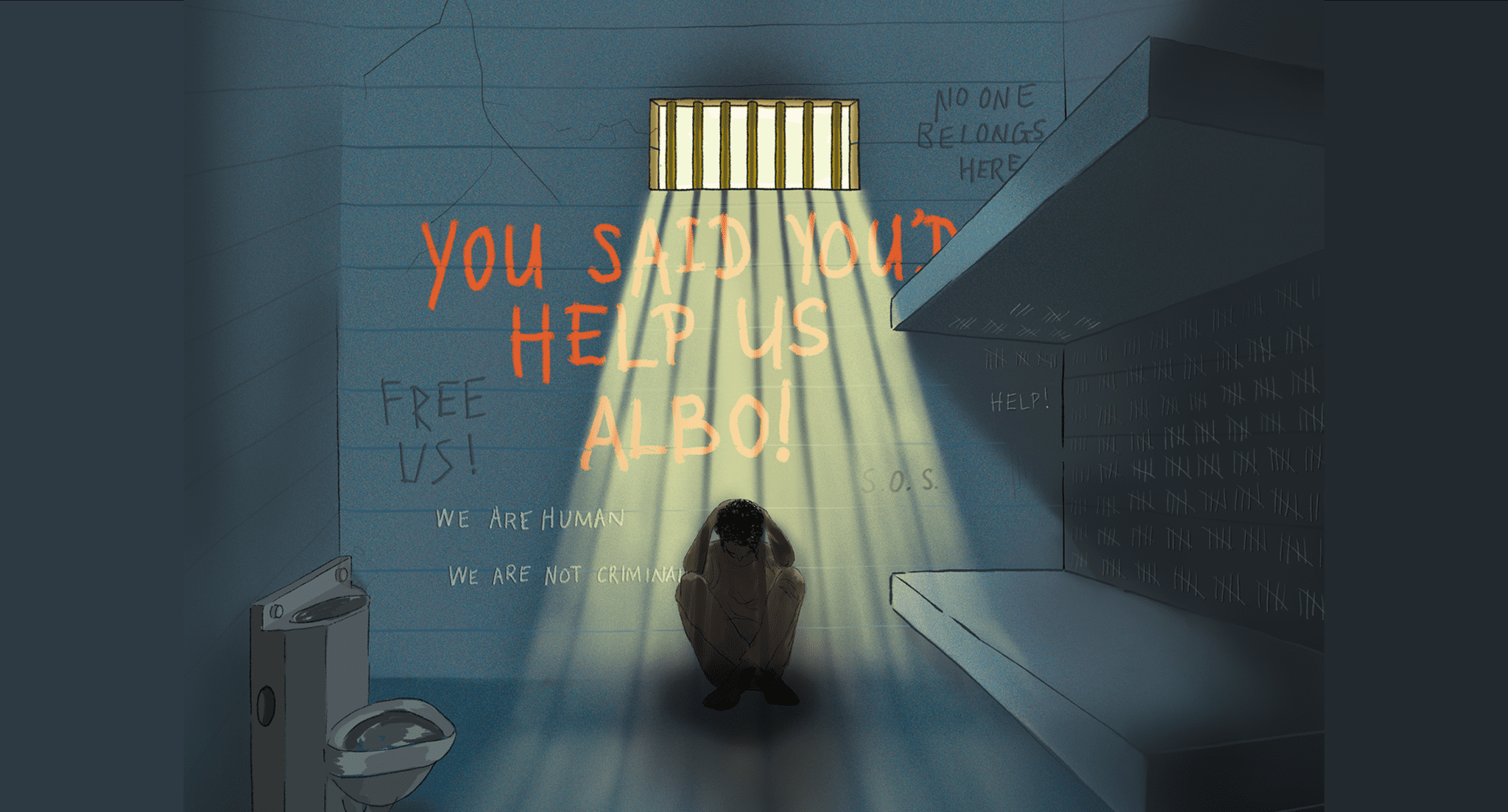

“Under the Liberals, there was no hope. But now, under Labor, there is.

“Anthony Albanese did say that no one will be left behind. He said he will clear out all the backlog of people that have been here for 10 years or more. I mean, it came out of his own mouth,” he says.

“Every week when he was in opposition, there were detainees from MITA in contact with Albanese’s office, and they were saying ‘Look, if he gets in, he’s definitely looking at changing the legislation’”.

Five months on from the election and changes to the Migration Act have not been discussed.

“The biggest thing I ask is for Albanese to please act – not just for 501s, but for refugees.

“We need to act as soon as possible to stop the deaths in custody here,” says Joey.

“The biggest thing I ask is for Albanese to please act – not just for 501s, but for refugees. We need to act as soon as possible to stop the deaths in custody here.”

“It’s hard for my kids. I’ve had many phone calls with them where they’ve said, ‘Dad, do you think you’ll go? We need you here.’

“All I can say to them is that ‘Sometimes in life there are things that are out of your control.’

“I tell them to ‘Work hard and live a good and righteous life, and to make sure to help people as much as you can’.

What else can I do?”

Today, there are 1,398 people held in immigration detention in Australia, and 501s make up 855 of them. A further 203 are held in an offshore Serco-run facility on Christmas Island, and 111 are currently in Nauru.

As of 30 June this year, the average period of time that people spend in immigration detention in Australia is a record high of 742 days.

A total of 144 people currently detained have spent more than five years in detention.

The average period of immigration detention in Canada, UK, and US is 24, 29, and 43 days respectively.

*name has been changed.

Thank you to Joey Tangaloa Taualii for sharing your story, and Ian Rintoul of Refugee Action Coalition Sydney for facilitating the interviews.