In Australia, the notion of mandatory military service is foreign to most young people. Naturally, we might relate it to a bygone wartime context; in our minds, it is dressed up in jingoism and butch glory, summoning forth grainy images of wars fought and won before we were born.

Though overshadowed in Australian media by its Northern counterpart, South Korea and Australia are fairly alike on paper: both liberal democracies boasting similar GDPs, with a remarkably strong relationship dating back to the Korean War. Both are long-time US allies, engage in complementary trade agreements, and even have similar emissions targets.

Yet our countries also differ in big ways – one being South Korea’s mandatory military service law and the culture surrounding it.

Of the 49 countries with conscription in 2022, South Korea is one of the most technologically, democratically, and economically advanced. This list includes other modernised, fairly progressive, and varyingly democratic nations; Sweden, Switzerland, Finland, Norway, Austria, Singapore, and Taiwan, to name a few.

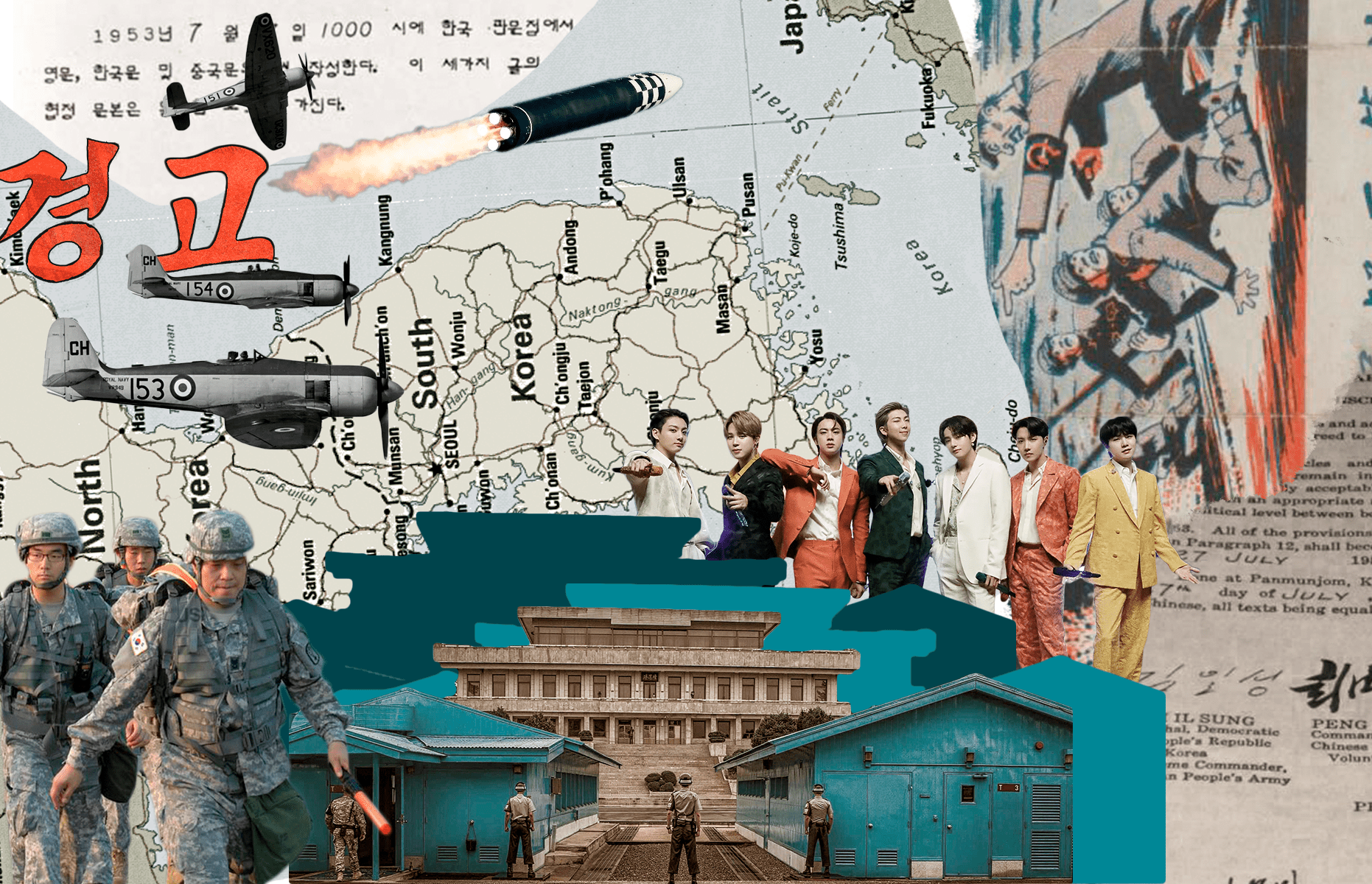

Like most of these nations, South Korea’s conscription laws arose from the state’s need for manpower during wartime, and today aim to deter a North Korean invasion, since peace between the two countries is maintained by the 1953 armistice. This means that, technically, the Korean Peninsula is still in a state of war – though South Korea’s swift modernisation in the past 70 years, and resulting military and economic superiority, has rendered a complete North-takeover quite inconceivable today.

Since 1957, military service has been compulsory for all able-bodied Korean men between the ages of 18 and 35. Men are typically required to complete 18-21 months of “active duty service”, which they become eligible for at the age of 18, and must commence by the time they are 28. Active duty means that men are engaged full-time; they usually live on a military base, and can be deployed at any time.

These circumstances are mandated by two legislative clauses: Article 39 of the Constitution of the Republic of Korea, and the Military Service Law. Often, South Korean men will wait until their early 20s to complete their service, rather than doing so immediately.

The idea of passing up almost two years of one’s young adulthood to involuntarily engage in military training is likely loathsome to many young Australians. And, I would imagine, to most 20-somethings who have not grown up with the prospect of this service contouring their younger years.

Audiences abroad are seldom exposed to the topic of Korea’s mandatory enlistment outside the context of the North Korean threat or celebrity-focused media (forcing an inevitable pause to male K-pop idols’ careers, for instance). In recent years, however, these historically-rigid laws have seen escalating challenges – most recently, by a rapid succession of conscription-related legislative changes since 2020, as well as intensified public debate around conscientious objection, alternative service, and exemption.

Within this context, Honi sought out three students from Seoul National University (SNU) in order to glean what young Koreans today think about mandatory military service. Receiving their insights would not have been possible without the help of my friend Sneha, a USyd student studying at SNU, who translated my questions, located the students, and recorded their answers for me, or my friend Alfred, who translated them back into English.

Two men aged 21 and 22 and one woman aged 21 participated. When asked about their feelings towards conscription, all participants believed it was a “necessary evil” to combat the threat of foreign invasion or interference.

“Looking at the overall global situation, I believe national defence is no longer a choice but a necessity,” said M, 21.

“[Mandatory military service] was created after the division of the country post-Korean war,” added F, 21. “I consider it to be an institution for preparing for war and a speedy reaction to emergency situations.

The history of South Korea explains much about this mentality; geo-politically, it is crowded by economic and military superpowers like China, Russia, Japan, and the US. It shares a militarised border with an aggressive and arcane enemy. Its modern iteration arose from violent and culturally-destructive foreign conflicts and occupations, experienced by just one or two generations, many of whom are still alive today.

M, 21, attributed “historical incidents” like the Japanese occupation, the North Korean and Chinese invasions (i.e, the Korean War), and “recent incidents” of North Korean aggression (signs of nuclear weapons testing, over 20 missile tests just this year) as reasons for the need for conscription.

However, M, 22, pointed out that “it’s hard to view the state essentially taking away your individual rights for just under 2 years as a proper or good thing”.

“Especially in today’s [Korean] society, where liberty and individual freedom is so important and stressed, military service can essentially be viewed as a conservative interruption to this [liberal society].”

South Korea has been a democratic country since 1987, prior to which the democratisation movement was violently suppressed by its military dictatorship for several decades. Despite this, conservative politics are generally more dominant in contemporary Korea. The polity has elected five conservative and three liberal presidential administrations since the establishment of democracy, with its most recent election in March of this year replacing Democratic Party of Korea president Moon Jae-in (liberal) with People Power Party’s Yoon Suk-yeol (conservative) by a mere 0.8 per cent margin.

M, 22 concluded: “We need to find a way forward [with conscription] that infringes on individual rights as little as possible with consideration of the opinions of everyday citizens.”

Presently, several situations exist wherein military service may be legally eschewed: if a candidate is not physically fit to serve, or if they are an extremely accomplished athlete (usually Olympic) or classical musician, whose career may be a valid measure of national contribution.

However, these laws appear to be pregnant for revision. The possible exemption from service of K-pop boy group and global phenomenon BTS has been a tendentious national topic since 2020. That year, the South Korean government revised its military service legislation to accommodate the group – dubbed the “BTS Law” – by permitting K-pop entertainers possessing government cultural medals (BTS being the only idols meeting that condition) to defer their enlistment until they are 30. This allowed the eldest member of BTS, who was turning 28 at the time, to continue his career.

Interestingly, most of the SNU students disagreed with granting idols such concessions.

“These idols are working for their own economic benefits first and foremost, and any additional benefit to the state from fans who come as tourists is not the main benefit – it’s just an unintended secondary benefit,” argued M, 21.

Both men felt that national service, instead of occurring as a side effect of fame, should be deliberate, measurable, and “contribute directly to the state”.

As of 18 October, the South Korean government officially announced that BTS will not be exempted from military service. This decision, suspending BTS’s artist activities, is likely set to cost Korea billions. According to the Hyundai Research Institute, the boy group contribute more than $3.6 billion to the South Korean economy every year — equivalent to 26 medium sized companies — and brought in one in every 13 tourists who visited South Korea in 2017.

Prior to this, however, public sentiment reflected rising acceptance of their exemption; a private survey earlier this year revealed that about 60 per cent of respondents supported the military exemption for BTS members. This is an increase from a similar survey in 2020, which showed that only 46 per cent backed the exemption, while 48 per cent opposed it.

The BTS situation intimates the broader national identity-shaping role fulfilled by conscription laws in South Korea.

According to M, 21: “Not just the current generation, but from the Korean Peninsula’s Gojoseon (ancient Korean civilization) era to today’s Republic of Korea, those who have been conscripted have been led to believe that [military service] is a noble act — as a kind of glamorisation and brainwashing.”

The current jail-time for conscientious objectors in Korea is 18 months. In 2020, the government introduced an ‘alternative service’ system, wherein those refusing military service on religious or other grounds are required to work in a jail or other correctional facility for 36 months, making it one of the longest alternative services in the world according to Amnesty International. Since the 1950s, some 19,000 conscientious objectors have been incarcerated in South Korea, some of the highest rates worldwide, with the majority being Jehovah’s Witnesses.

When asked about whether those evading military service should be punished, all students answered in the affirmative. M, 22, argued that widespread evasion “would threaten the existence of the state – and so, it’s inevitable that the state would have to punish it.”

In August of this year, the government dropped charges for the first time against a citizen rejecting military service (including alternative service) due to Jehovah’s Witness beliefs.

Pointing to this case, F, 21 said: “It’s hard to receive exemption from the courts and be tolerated as a minority in objection to military service. Even if it is exempted by the courts, one would find a lot of social stigma from evading military service.”

Of course, viewing conscription through the narrow frame of national defence omits its use as a persuasive ideological tool of the state.

According to a 2018 article by Korean scholar Ihntaek Hwang: “[South Korean] conscription has enabled nation-wide militarised political education, attempted to impose false ideals of equality, and provided the public with an ideal masculinity. This leads to the observation that the state’s imposition of who gets to be ‘us’ and who gets to be ‘them’, a key idea of national security, has been heavily influenced by conscription.”

While the South Korean government and its highest courts have repeatedly criminalised objection to mandatory military service in the name of national security, Hwang claims that “‘national security’ is a discursive construction, subject to change, as history is never short of examples of insecurities committed in the name of national security.”

I spoke to a Korean-Australian friend at USyd, who is a dual citizen, and believes that the current military service model is flawed.

“[Among Koreans] there’s this feeling of needing to be economically and militarily powerful to make sure we can defend ourselves and have a distinct culture among other major players,” he told me.

“That being said, I think conscription is now unnecessary and inefficient. Korea is one of the wealthiest and most technologically advanced countries in the world. I think regular recruitment and investment into defence tech (which the government has really ramped up) is enough,” he said.

“We’ve seen from the Ukraine-Russian war that in the modern age, it’s not manpower but technology and sophisticated weapons that win wars.”

Korea currently ranks eighth in the world in weapons exports, with its share of the global market nearly tripling over the past five years to 2.8 per cent.

“Also male recruitment is creating huge issues with antifeminism and misogyny recently,” he added. “A lot of young men feel like they’re taking on an unfair burden (true) but are going about blaming women in non-constructive ways.”

The SNU students had mixed reactions to the single-gendered model of conscription. While the female student believed women could demonstrate state service through non-military means, male participants believed it was unfair or unconstructive to the purpose of national defence.

South Korean national identity and gendered ideals are unequivocally intertwined; conscription, as an ideological tool, inevitably shapes both. Insook Kwon, a former South Korean labour organiser and the first woman to bring sexual assaut charges against the Korean government, argues in a 2020 article that mandatory military service stabilises the idea that “men sacrifice their personal interests for the larger-framed interests, which women do not.” With feminism still a relatively controversial and misunderstood movement in the country, it is ostensibly harder for such ideas to enter the mainstream.

Clearly, mandatory military service remains generally favourable among the group of highly-educated young South Koreans interviewed. However, the tide appears to be turning towards a more flexible model of national service in recent years, with the legalisation of alternative service, dropping of charges against a conscientious objector, and the BTS situation. However, there is little to suggest that this trend will continue or be welcomed by the Korean public. As South Korea strives to fashion itself into a principal world power, its parallel socio-cultural transformation is only beginning to find its feet.

This article was updated on 18 October to reflect the recent decision not to exempt BTS from military service.