Graduation ceremonies are typically billed as celebratory events, but mine was more like a company awards ceremony; full of glitz and glamour, and signifying nothing. We lined up in black robes to receive white certificates, given out after lengthy speeches lauding the status quo, corporate jobs, and a ‘skills-based’ curriculum. Like every cohort before us, we were lauded as the “brightest minds of our generation”, equipped with “transferable skills,” ready to take on the “important jobs” for building the Australian economy.

The University of Sydney’s marketing team had been working overtime that year, making red banners to blanket Eastern Avenue with “#Leadership”. “Leadership for good starts here,” they read. The ads suggested we were “unlearning” old ways of thinking. But now, looking at my graduation class all these years later, all that we seem to have unlearnt was our commitment to ethical integrity. We had learnt skills, but a values-based education had entirely eluded us (or, we had learnt skills, but almost nothing about values).

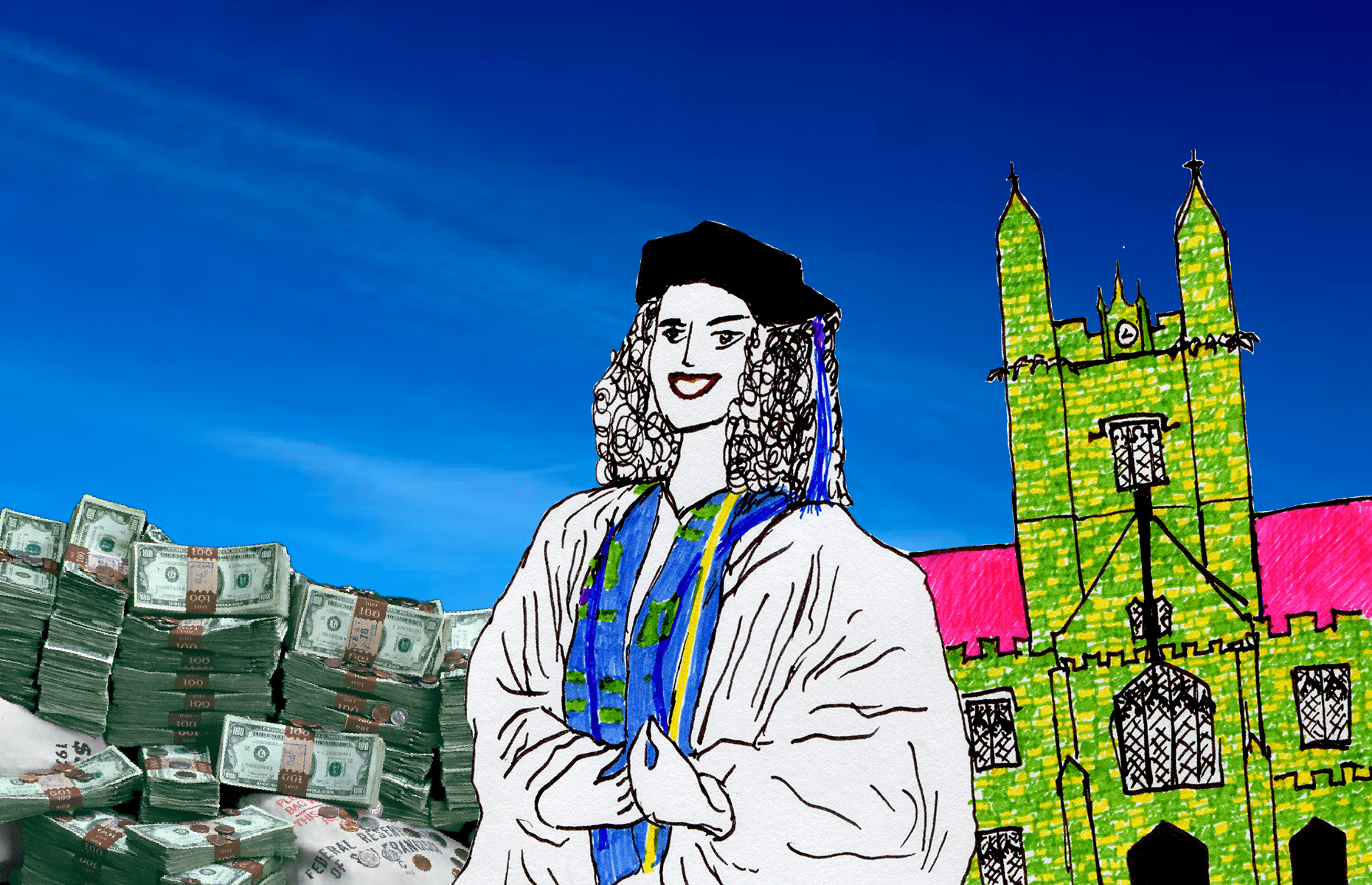

Ten years on, these classmates have now all graduated again, into the ranks of the Border Force or into the headquarters of big oil, coal, or gas. Many more have dedicated their lives to becoming reverse Robin Hoods, transferring wealth from the poor to the rich. Others staff the forefront of cutting edge scientific research on how to improve our use of drones… in war zones. All of these graduates are from the University of Sydney.

It is unclear what exactly my generation got out of USyd, but it is clear that the alumni posters could’ve used a bit more honesty. Committing a generation to a skills-based curriculum with little to no mention of ethics, morality, or even religious thinking, has consequences. Studies of modern law schools, for example, show that a skills-based curricula turn their students away from public service, and toward pursuing and advancing solely corporate ends.

Marie Iskander, UNSW Law Class of 2015, writes: “Despite being reluctant about pursuing a clerkship, because I didn’t feel drawn towards private law, I was convinced by peers, older lawyer friends and, of course, HR from the big law firms that “this is the right path” and “what do you have to lose?”

But the losses are always real and significant. Corporate firms take the most productive and formative years of someone’s life. Meanwhile, graduates, having only been taught a skills education, understandably find it hard to know what to use those skills for.

The many lies my class were told at graduation centred on an invisible ideology. The ideology had a few core beliefs to it. First, education is only ever a means to an end, and that end is to get a job at a superficially elite institution, regardless of the ethics of that institution. Second, activities that don’t make money are always childish. Third, maturity is to be determined by compliance with corporate thinking, rather than independent thinking. This ideology had been re-packaged under the terminology of “the real world,” “growing up,” and “accepting responsibility” for our lives.

On the face of it, these beliefs are appealing. Sydney is one of the most expensive cities in the world, and so anything that celebrates money-making is intrinsically attractive. Corporate life is glamorous, with cocktail evenings, gleaming phallic skyscrapers, and free cruises on the harbour. Meanwhile, alternative lifestyles are risky, unrewarding, and socially isolating. So, the choice is a simple one. Conform, or become an outcast.

Like most ideologies however, corporate propaganda has illogical underpinnings. A Big Four accountant once remarked that I had Peter Pan syndrome – the inability to grow up – because I wanted to write a novel. The presumption being that only children write novels. Even more tragically, a corporate lawyer once told me they believed that “it’s normal to never make friends after university.” This was someone working sixty hours a week. Conversely, a consultant told me “people who don’t work on weekends are lazy.” This, they submitted, was the real work we ought to get used to shortly after graduation. Compromise and disappointment.

The University of Sydney likes to hold itself up as a successor to the great universities of the past. Sydney’s Latin motto, “Sidere mens eadem mutato,” translates to “The same learning under new stars.” This refers to the legacies of Oxford and Cambridge. So too, our quadrangle mirrors the architectural style of both these universities.

But the commitment of our University to a new, corporate ideology is not even that “same learning.” Oxford and Cambridge celebrate the arts, music, philosophy — even if that appreciation is often reserved for elite, narrow forms of it. They find and celebrate a place for religion and mediaeval history, courses that have been eroded by many cuts at USyd. They teach certain values necessary for life, not just skills that will date by the year. Speaking to the Vice-Chancellor of Oxford, Louise Richardson, I asked her how they managed this continued commitment to a moral education.

She replied, slightly baffled, “that’s how it’s always been, and how it always will be.”