The second workshop in the ‘Art in Place’ series took place last week over Thursday and Friday, this time focusing on Judy Watson’s work jugama (2020); see Week 4, Sem 2 Honi for the first in the series. The goal of the workshops is to introduce students to Indigenous artworks on campus, encourage them to think deeply about the work and write a reflective response — which is collaboratively edited on the second day with Art History lecturers and University curators of Indigenous art.

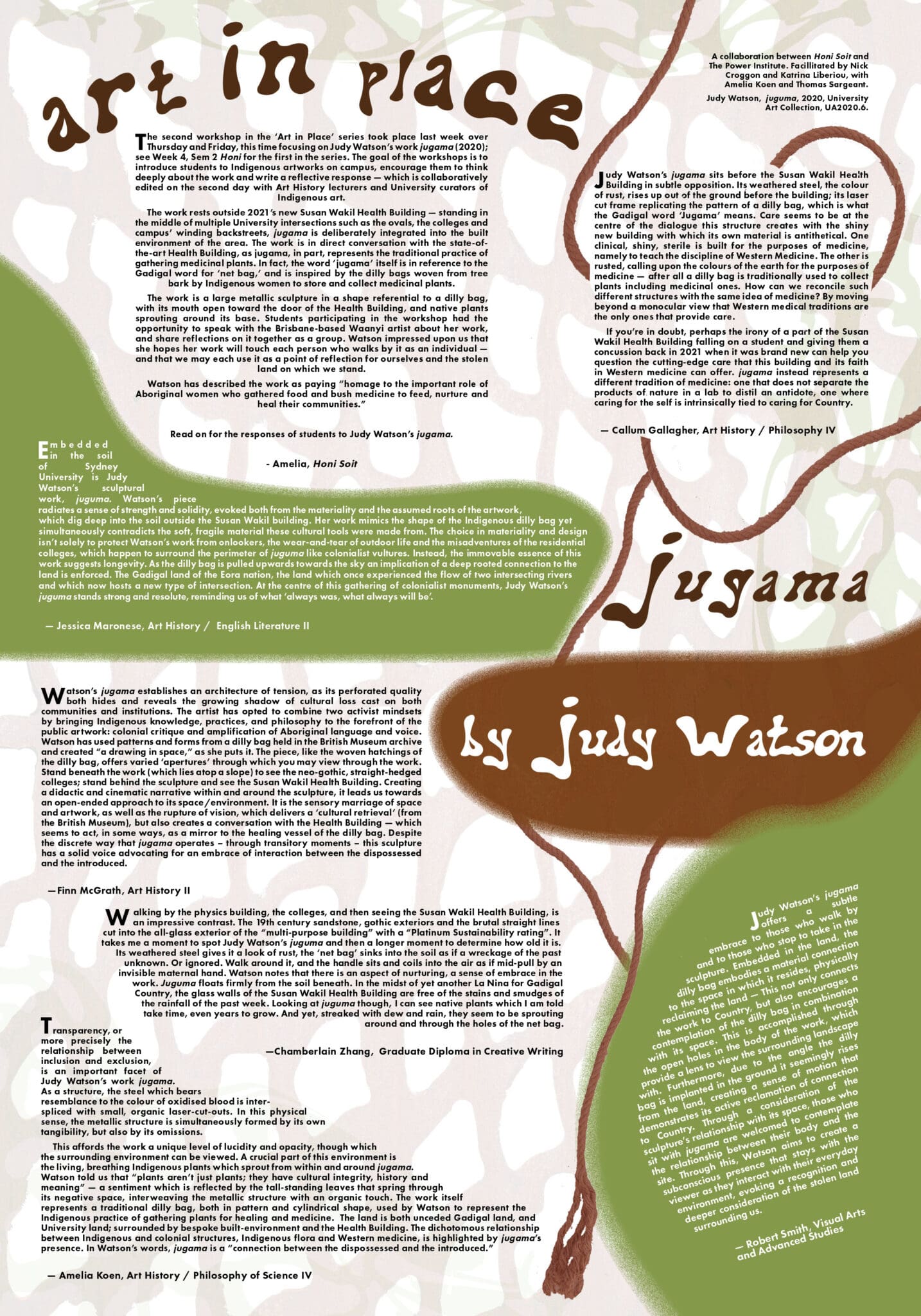

The work rests outside 2021’s new Susan Wakil Health Building — standing in the middle of multiple University intersections such as the ovals, the colleges and campus’ winding backstreets, jugama is deliberately integrated into the built environment of the area. The work is in direct conversation with the state-of-the-art Health Building, as jugama, in part, represents the traditional practice of gathering medicinal plants. In fact, the word ‘jugama’ itself is in reference to the Gadigal word for ‘net bag,’ and is inspired by the dilly bags woven from tree bark by Indigenous women to store and collect medicinal plants.

The work is a large metallic sculpture in a shape referential to a dilly bag, with its mouth open toward the door of the Health Building, and native plants sprouting around its base. Students participating in the workshop had the opportunity to speak with the Brisbane-based Waanyi artist about her work, and share reflections on it together as a group. Watson impressed upon us that she hopes her work will touch each person who walks by it as an individual — and that we may each use it as a point of reflection for ourselves and the stolen land on which we stand.

Watson has described the work as paying “homage to the important role of Aboriginal women who gathered food and bush medicine to feed, nurture and heal their communities.” Read on for the responses of students to Judy Watson’s jugama.

Callum Gallagher, Art History / Philosophy IV

Judy Watson’s jugama sits before the Susan Wakil Health Building in subtle opposition. Its weathered steel, the colour of rust, rises up out of the ground before the building; its laser cut frame replicating the pattern of a dilly bag, which is what the Gadigal word ‘jugama’ means. Care seems to be at the centre of the dialogue this structure creates with the shiny new building with which its own material is antithetical. One clinical, shiny, sterile is built for the purposes of medicine, namely to teach the discipline of Western Medicine. The other is rusted, calling upon the colours of the earth for the purposes of medicine — after all a dillybag is traditionally used to collect plants including medicinal ones. How can we reconcile such different structures with the same idea of medicine? By moving beyond a monocular view that Western medical traditions are the only ones that provide care.

If you’re in doubt, perhaps the irony of a part of the Susan Wakil Health Building falling on a student and giving them a concussion back in 2021 when it was brand new can help you question the cutting-edge care that this building and its faith in Western medicine can offer. Jugama instead represents a different tradition of medicine: one that does not separate the products of nature in a lab to distil an antidote, one where caring for the self is intrinsically tied to caring for Country.

Jessica Maronese, Art History / English Literature II

Embedded in the soil of Sydney University is Judy Watson’s sculptural work, juguma. Watson’s piece radiates a sense of strength and solidity, evoked both from the materiality and the assumed roots of the artwork, which dig deep into the soil outside the Susan Wakil building. Her work mimics the shape of the Indigenous dillybag yet simultaneously contradicts the soft, fragile material these cultural tools were made from. The choice in materiality and design isn’t solely to protect Watson’s work from onlookers, the wear-and-tear of outdoor life and the misadventures of the residential colleges, which happen to surround the perimeter of juguma like colonialist vultures. Instead, the immovable essence of this work suggests longevity. As the dillybag is pulled upwards towards the sky, an implication of a deep rooted connection to the land is enforced. The Gadigal land of the Eora nation, the land which once experienced the flow of two intersecting rivers and which now hosts a new type of intersection. At the centre of this gathering of colonialist monuments, Judy Watson’s juguma stands strong and resolute, reminding us of what ‘always was, what always will be’.

Finn McGrath, Art History II

Watson’s jugama establishes an architecture of tension, as its perforated quality both hides and reveals the growing shadow of cultural loss cast on both communities and institutions. The artist has opted to combine two activist mindsets by bringing Indigenous knowledge, practices, and philosophy to the forefront of the public artwork: colonial critique and amplification of Aboriginal language and voice. Watson has used patterns and forms from a dillybag held in the British Museum archive and created “a drawing in space,” as she puts it. The piece, like the woven hatchings of the dillybag, offers varied ‘apertures’ through which you may view through the work. Stand beneath the work (which lies atop a slope) to see the neo-gothic, straight-hedged colleges; stand behind the sculpture and see the Susan Wakil Health Building. Creating a didactic and cinematic narrative within and around the sculpture, it leads us towards an open-ended approach to its space/environment. It is the sensory marriage of space and artwork, as well as the rupture of vision, which delivers a ‘cultural retrieval’ (from the British Museum), but also creates a conversation with the Health Building — which seems to act, in some ways, as a mirror to the healing vessel of the dillybag. Despite the discrete way that jugama operates – through transitory moments – this sculpture has a solid voice advocating for an embrace of interaction between the dispossessed and the introduced.

Robert Smith, Visual Arts and Advanced Studies

Judy Watson’s jugama offers a subtle embrace to those who walk by and to those who stop to take in the sculpture. Embedded in the land, the dillybag embodies a material connection to the space in which it resides, physically reclaiming the land — This not only connects the work to Country, but also encourages a contemplation of the dillybag in combination with its space. This is accomplished through the open holes in the body of the work, which provide a lens to view the surrounding landscape with. Furthermore, due to the angle the dillybag is implanted in the ground it seemingly rises from the land, creating a sense of motion that demonstrates its active reclamation of connection to Country. Through a consideration of the sculpture’s relationship with its space, those who sit with jugama are welcomed to contemplate the relationship between their body and the site. Through this, Watson aims to create a subconscious presence that stays with the viewer as they interact with their everyday environment, evoking a recognition and deeper consideration of the stolen land surrounding us.

Amelia Koen, Art History / Philosophy of Science IV

Transparency, or more precisely the relationship between inclusion and exclusion, is an important facet of Judy Watson’s work jugama. As a structure, the steel which bears resemblance to the colour of oxidised blood is inter-spliced with small, organic laser-cut-outs. In this physical sense, the metallic structure is simultaneously formed by its own tangibility, but also by its omissions.

This affords the work a unique level of lucidity and opacity, though which the surrounding environment can be viewed. A crucial part of this environment is the living, breathing Indigenous plants which sprout from within and around jugama. Watson told us that “plants aren’t just plants; they have cultural integrity, history and meaning” — a sentiment which is reflected by the tall-standing leaves that spring through its negative space, interweaving the metallic structure with an organic touch.

The work itself represents a traditional dillybag, both in pattern and cylindrical shape, used by Watson to represent the Indigenous practice of gathering plants for healing and medicine. The land is both unceded Gadigal land, and University land; surrounded by bespoke built-environment and the Health Building. The dichotomous relationship between Indigenous and colonial structures, Indigenous flora and Western medicine, are highlighted by jugama’s presence. In Watson’s words, jugama is a “connection between the dispossessed and the introduced.”

Chamberlain Zhang, Graduate Diploma in Creative Writing

Walking by the physics building, the colleges, and then seeing the Susan Wakil Health Building, is an impressive contrast. The 19th century sandstone, gothic exteriors and the brutal straight lines cut into the all-glass exterior of the “multi-purpose building” with a “Platinum Sustainability rating”. It takes me a moment to spot Judy Watson’s juguma and then a longer moment to determine how old it is. Its weathered steel gives it a look of rust, the ‘net bag’ sinks into the soil as if a wreckage of the past unknown. Or ignored. Walk around it, and the handle sits and coils into the air as if mid-pull by an invisible maternal hand. Watson notes that there is an aspect of nurturing, a sense of embrace in the work. juguma floats firmly from the soil beneath. In the midst of yet another La Nina for Gadigal Country, the glass walls of the Susan Wakil Health Building are free of the stains and smudges of the rainfall of the past week. Looking at juguma though, I can see native plants which I am told take time, even years to grow. And yet, streaked with dew and rain, they seem to be sprouting around and through the holes of the net bag.