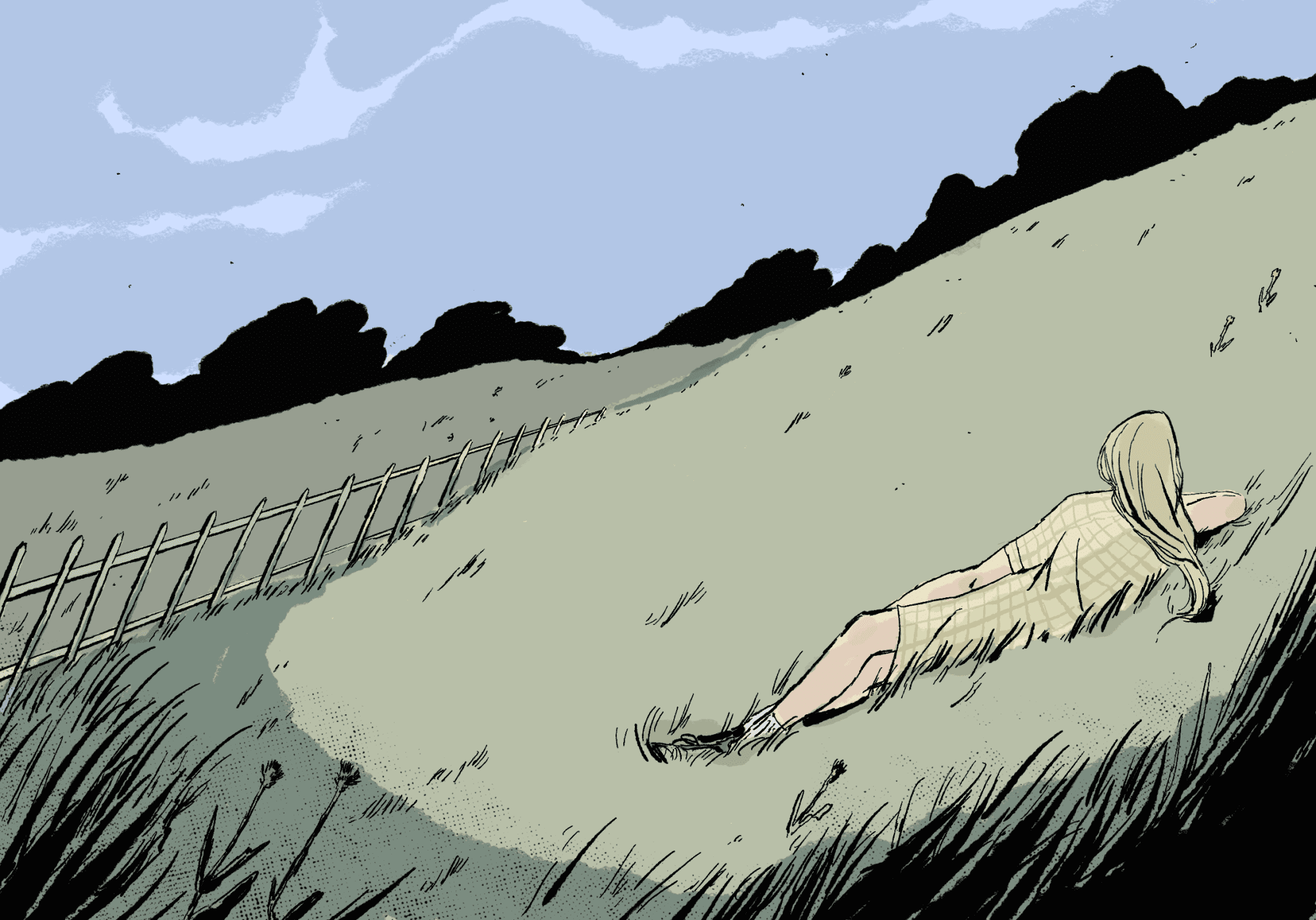

In the opening of Colm Bairéad’s The Quiet Girl, we are struck by the calls of Cáit’s siblings telling her to come home. The camera falls to the young girl lying in a field. It is rural Ireland, a family living in abject poverty, and at its centre, a neglected child without a voice.

And so begins a tale of unspoken connections and the beautiful nuances of human relationships. The film moves slowly, and creeps up on you through an accumulation of little moments of sensitivity.

The premise is simple. It is 1981. There are hunger strikes in the North, and the country is in chaos. In this story, however, the outside world is not in overt focus — here, we have a timeless rural landscape, and nine-year-old Cáit is one of many siblings in a dysfunctional household. Cáit’s mother is yet again pregnant, and with too many mouths to feed, Cáit is sent away to live with her distant aunt, Eibhlín, and her husband Seán, on their farm.

The lack of welfare support for struggling families comes across through the portrayal of Càit’s household. Recession in the late 1970s and early 80s culminated in deep cuts to Ireland’s already poor provision of health and social housing. Contraception was banned, meaning families grew too large to sustain themselves. The inattentive treatment of Càit by her parents is not without reason; circumstances make familial care strained and difficult. The film is in many ways a raw portrayal of hardship and pain.

The Quiet Girl provides a faithful adaptation of Irish writer Claire Keegan’s 2010 short story, Foster. It is rare for a film to reproduce a written text so well that it perhaps even transcends it. The film visualises Keegan’s story with fluidity and thoughtfulness, and subtly renders expression through its characters — particularly Catherine Clinch, who excels in her role as young Cáit. Bairéad’s evocative portrayal of the Irish countryside, and his script that says only as much as is needed, makes for a beautiful film.

As for the craft behind the film, cinematographer Kate McCullough hinges on ostensibly insignificant images and points in time: she ultimately emphasises an undercurrent of unpretentious beauty. We watch the panning of the afternoon sun, piercing through the trees as Cáit’s father drives her to the farm, and we inspect the repetitive close-ups of Eibhlín brushing Cáit’s hair — ninety-eight, ninety-nine, one hundred…

The film renders a tenderness that the viewer is privy to from the early interactions between Eibhlín and Cáit: Eibhlín tactfully attributes Cáit’s wet sheets to another cause, holds her hand walking her through the paddocks in her too-big gumboots, and patiently sits by her side as she practises reading aloud.

However, it is perhaps more affecting to witness the gradual thawing of Sean’s frosty demeanour towards the young child over the course of the film. Through Cáit’s child-eyes, we watch as Sean’s initial gruffness softens into sincere affection. Where the two share an intimate conversation by the water, Sean tells her of the lost horses that fishermen find out at sea. For the first time, someone affirms to Cáit that her quietness is not at fault: he tells her, in a quintessentially Irish cadence, “You don’t have to say anything. Always remember that. Many’s the person missed the opportunity to say nothing and lost much because of it.” They sit in silence and watch the moonlight flicker on the receding tide, and a deep mutual understanding is conveyed without words.

This was a particularly touching scene for me. As someone who has always been quiet, and consistently told to ‘speak up’ throughout my childhood and school years, it was beautiful and affirming to see quietness recognised as a virtue. In this film, it is the silent moments that have the most profound impact.

Landscape and place are integral to the film’s symbolic meaning. From the very beginning, McCullough constructs a dichotomy between the inside and outside, and Cáit lies alone in a field in escape from her seemingly bleak family household. We watch Cáit at school, as she sits miserably in class, and at lunchtime runs away over the schoolyard fence. We gaze at the farm over the summer, as Caít runs to the letterbox through dappled sunlight, and the trees meet over the path in leafy embrace. It is not simply nature that is the source of Cáit’s contentment and freedom — it is, above all, the joy of being listened to and understood.

As we watch the film, we see Eibhlín and Seán become to Cáit the parents she never truly had. They treat her with a kindness so foreign to her in the beginning, that it is only over the course of the film that we witness her coming to understand that she has found a home in these two people — a home that is at odds with the one she had left behind. That home is cold and dark and bleak: the baby is crying and there is not enough to eat; the father drinks too much and is late to bring in the hay. When it comes time for Cáit to return home, she doesn’t want to go.

An understated piece of art, The Quiet Girl is one of those films that stays with you long after you leave the cinema. In few words, it speaks to being quiet in a noisy world — perhaps the deepest connections transcend language.