“Every town in this country has one of these,” she said.

Norma stood with Jeremy. They were roughly the same height. If you stood from behind and saw only their backs and stood far far away, they could be the same age.

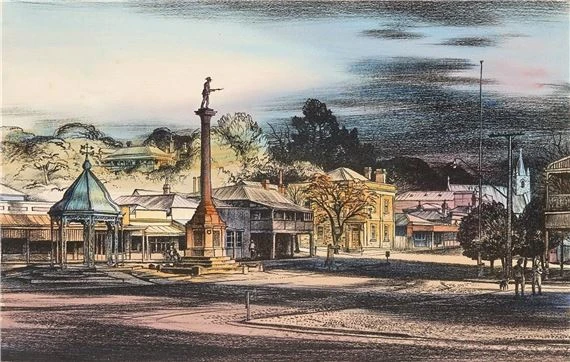

She pointed up at the bronze man in the afternoon heat. He towered above them. “This is our history,” she said.

Jeremy’s little face looked up at the bronze man and his pointy rifle and his fancy uniform and the sculpted ripples in his fancy uniform from the wind.

Jeremy licked his index finger and put it in the air and felt nothing.

Norma gave him a closed-mouth smile. Beyond her lips was a set of yellowed teeth. The wrinkles around her lips went deep.

She pointed to the script on the pedestal beneath the bronze man.

“Do you know what those words are?” she said.

“No?” he said.

Jeremy had the habit of inflecting the end of his sentences. They all sounded like questions. “Those are the names of men,” she said.

Jeremy said nothing.

“They did something very special for us. Do you know what they did for us?”

“No?” he said.

“They fought so you could be safe. So you could go to school and your mummy could go to work.”

“Oh?” he said.

“Yes. They were brave. And what they did was right.”

“Brave and right?” he said.

“Yes. Brave and right. Good boy.”

Norma took Jeremy’s hand and the two walked down the wide empty road to the house and went inside. It was cool from the air conditioning and Jeremy’s mother was making sandwiches in the kitchen.

The three of them sat on the veranda and ate the sandwiches and drank lime cordial, diluted twice as much as normal. The cicadas buzzed in the dead hot air. They sat and ate in silence and when they were finished Jeremy’s mother collected the plates and went back into the kitchen.

At eight in the evening Jeremy was put to bed. The three sat in the small bedroom as the mother read the son a bedtime story. In the corner was a nightlight. It let off an amber glow and hummed softly. Jeremy fell asleep before she could finish the story.

Jeremy’s mother sat there in the half-dark for a while. The boy lay on his side, breathing steadily. She had her hand close to him, just out of reach of his little chest when it swelled like a cresting wave.

Norma put her hand on the mother’s shoulder, but she did not look up.

Norma went out onto the veranda and down the steps and into the warm night. She walked down the road past the bronze man, pointing a small flashlight into the wide dark. There was a bench to the side of the road. She sat wearily and turned off the flashlight. She lit an unfiltered cigarette, letting it burn out slowly between her fingers.

It was quiet. Not even a breeze.

When the cigarette burned out, she widened her fingers and let the butt drop to her feet and sat still, thinking in the quiet.

For no reason at all, she thought about her youth. She remembered when couples slow-danced at the local hall, and when it was so cold you could barely feel your feet and when parents took their children for ice cream near the water. For no reason at all, she thought about great big cargo ships and waves and tears.

She fumbled for the cheap lighter in her pocket. She lit another unfiltered and took long, hard inhales. She felt her head buzz and swell. She let time pass.

In between cigarettes she thought and listened to herself wheezing for air.