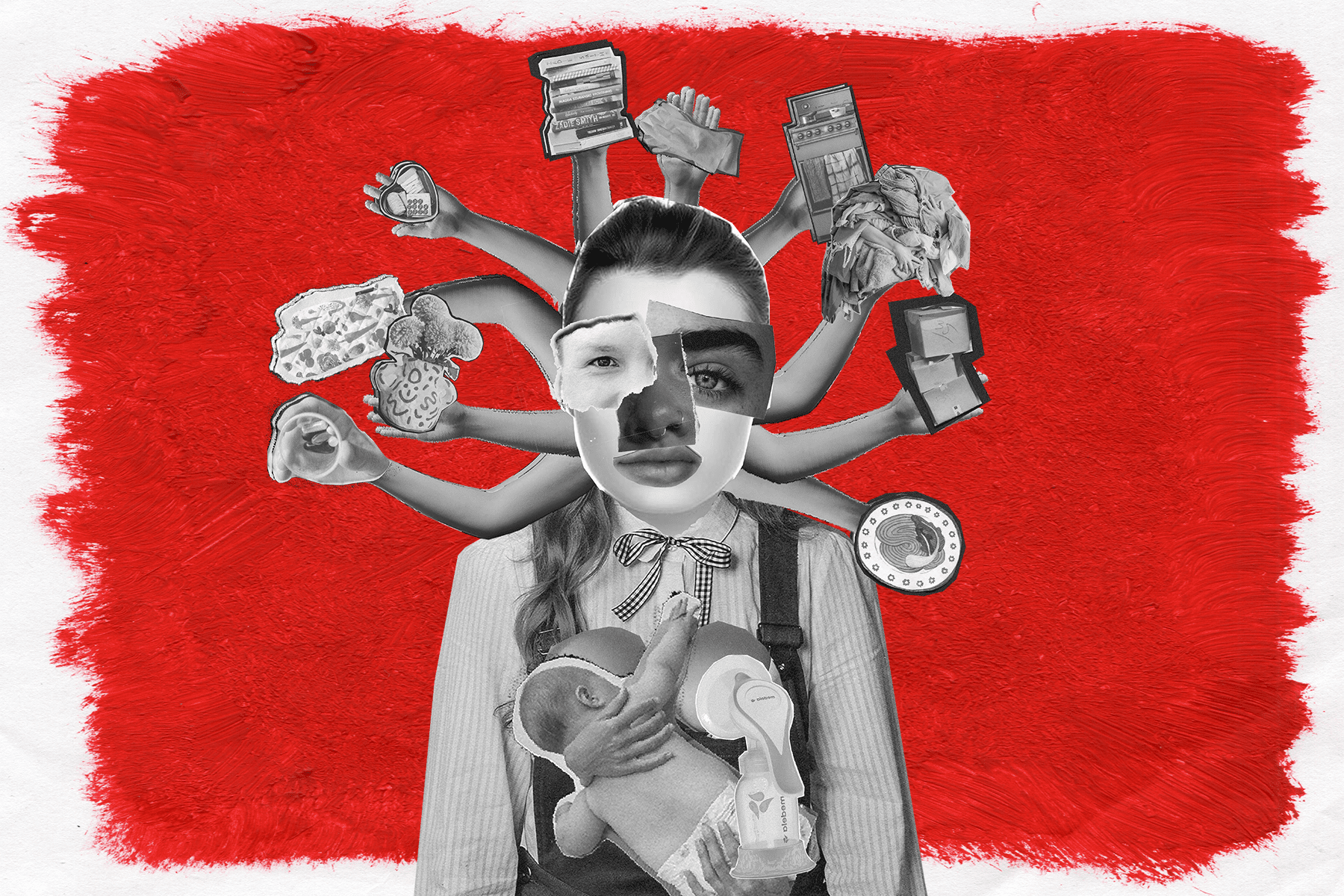

There are 2,650,000 million unpaid carers in Australia, and at least 235,000 of these are young carers. Despite the amount of students that are carers, structural support at the University of Sydney is limited, or non-existent, for students who have additional caretaking responsibilities.

In Australia, a young carer is defined as a person aged 25 or younger looking after a friend or family member with a disability, mental illness, chronic condition, terminal illness, or who is elderly. When the phrase “caring” is evoked, most imagine a mother looking after a child. This model of caring has influenced many of the support structures available for carers at the University. Many support structures for carers are grouped with those for parents. Both the young people who are carers and those they care for tend to transcend this conception, often leaving them unsupported by these traditional carer oriented support structures.

Young carers are a difficult demographic to track — many young people who have additional caretaking responsibilities do not identify as “young carers”. Some may find themselves suddenly in a position of caretaking after a loved one is diagnosed with an illness, while others have grown up with additional responsibilities, and so it becomes a normal part of their lives.

Sandra Kallarakkal is in her fourth year of a Bachelor of Arts and Secondary Education. Her dad is a renal patient, who has had two kidney transplants and has been on dialysis throughout her life. Like many young carers, her responsibilities and caretaking duties are not easily represented on paper.

“I’ve got a lot of responsibilities, because my mum works, and I’ve got a younger brother who’s now eleven. My dad had dialysis three days a week, so I was dropping [my brother] off at school and picking him up and taking him to piano lessons, and soccer. I also think there’s the emotional labour of having to deal with medical problems and helping out with bills and all of that.”

Sandra was quick to admit that every student has their own struggles, whilst adding that “at uni, a lot of people have timetables where they go into the library and sit down for a bit and do their assessments. Whereas for me, especially in my first couple of years of uni, I went only for class, I finished class, and I would immediately have to go home because I’ve got other responsibilities.”

“It feels a bit isolating because people are doing things that you don’t have the time to do.”

Like Sandra, Isabella* is another young carer who found it isolating at university, sharing that “it really weighed on me when I was away from my family and hanging out with my friend’s who were just easy breezy, having the time of their lives at uni, which is what I wanted. It just kind of made me feel worse, because they just had no idea what I was going through — which isn’t their fault, obviously.”

She explained that going out and having a ‘normal’ time came at the direct cost of her sister’s care, and her family’s well-being as “they were one man down.”

Isabella studies a STEM degree and cares for her younger sister, who is disabled and non-verbal. Her sister became sick which “presented in her screaming for hours each day, no-stop. It was terrible.”

“It wasn’t until later that [doctors] finally figured out two things that were causing it, which would’ve been just immediately diagnosed [had she not had disabilities], but we faced a lot of ableism.”

Isabella had a period of time where she found it too difficult to live at home full time with her sister and found herself couch-surfing at friend’s houses.

“I would sign up for a full load, knowing I would fail two units, because I needed to be a full-time student in order to receive youth allowance.”

Navigating intersecting structural disadvantages is common for student carers. Young carers are more likely to come from families who are economically disadvantaged and be from a non-English speaking background. Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people are almost twice as likely to be young carers, and young carers themselves are more likely to have a disability or long-term health condition. This means that young carers are in particularly vulnerable positions.

Despite this, young carers at the University of Sydney are not adequately supported — further entrenching inequities.

“I have felt a culture of apathy from a lot of my lecturers.” Isabella stated.

“I used to get emails from lecturers saying I noticed you weren’t in class today. I would reply saying I have these caring duties. I’d get no response and they’d be really cold to me in person.”

Sandra echoed these sentiments, with some of her classes having a 90% attendance rate for lectures and the unit coordinators not being understanding. She also described the difficulties in fitting in the experience of being a student carer into the narrow categories offered by the University when applying for special considerations.

“I have a funny time looking through the list [that the university provides] because I always have to pick an exacerbation of an ongoing condition and then they’re like, Oh, is this ongoing?

“And you’re like, yes. And then it asks will that affect you in the future? And it’s like, yes, it will. And then it says, have you applied for disability provisions? I’m like, no, cause it doesn’t apply. It’s that same process every single time. It feels a little bit demeaning.”

Both Isabella and Sandra do not fit the traditional understanding of what a carer looks like — they are young and care for someone who isn’t their child. If they are left unsupported by the support structures available, how does the University fare when someone fits the conventional mould of caregiver?

Not very well either.

Eva Midtgaard is a parent and student, studying a higher degree by research at the University of Sydney.

Last year, when Eva was pregnant, she suffered significant health issues related to the pregnancy. Eva said in a statement to Honi, “My stipend did not have any legal hours for me experiencing health related issues due to my pregnancy. I had to suspend my studies, meaning I had no income, due to pregnancy related health issues.

“That was quite shocking to me.”

These issues continued after Eva’s child was born. There are no childcare options for Eva should she need to take classes from 6pm-9pm, the time when most postgraduate students teach and have scheduled classes. There was nothing in Eva’s contract related to maternity leave, and Eva’s supervisors just assumed that she would work from home — despite it further isolating her from her academic peers, and her not wanting to do so.

Eva breastfeeds her child and must pump every two hours to ensure her milk production continues. The parenting facilities that the University initially told her to use were a twelve-minute walk away from her place of work.

Eva would have to go here a minimum of three times across her workday, walking twenty-four minutes in total, and pumping for twenty-five minutes — meaning that she would, on average, spend two hours and thirty minutes per day doing this.

Post doctorates have their own offices in the building that Eva worked in. She spoke of her frustration at not being offered an office to use to express milk, if she needed it.

“I wouldn’t waste any time [if I was offered an office]. I would be able to continue to work through expressing milk.”

It was only after Eva indicated that she would raise a grievance against the school for discriminatory practices, and emailed student services multiple times that alternative arrangements were made — but this should not be the standard.

In a comment to Honi, a USyd spokesperson said, “We are committed to providing a range of support for students with carer responsibilities, including resources to help find childcare providers, facilities for parents on campus, access to the Student Parents and Carers Network and access to health and wellbeing services.

“Student carers can apply for special consideration or an adjustment to their timetable in the event of unexpected primary carer responsibilities. Work is underway to allow students with ongoing caring responsibilities to be supported by an individual academic plan outlining their support needs for each semester, without needing to re-apply for special consideration for each individual academic activity.”

Considering the experiences of students with caring responsibilities and the University’s bureaucracies, this statement rings hollow. One may question the “commitment” that USyd claims to have when supporting student carers, when it has so little to show for that commitment. Neither Sandra nor Isabella have been helped by special considerations. Isabella was unaware that she could apply for an adjustment in her timetable after census date until months after she had failed all but one subject for that semester. Neither had found comfort in the faceless bureaucracies of USyd that the statement directs students to.

The University said that their data on student carers was “not available”. SUPRA, the SRC, and the Young Carers Association were consulted in the University’s work towards carers being able to access academic plans, with this “aiming” to be implemented in Semester Two this year — as per University spokesperson.

Despite much of USyd’s statement focusing on parents who are caring for their child, this does not add up in Eva’s experience. They assumed that she would work from home, initially only offered a breast-feeding room a twelve minute walk away from her place of work, and have no childcare available for her child, should Eva need it while teaching or studying at the times when the majority of post graduate classes are scheduled.

The University’s main wellbeing service — CAPS — didn’t help Sandra much, “I remember in the very first year of uni, within the first couple of weeks, I had a chat with CAPS about [if I could] apply for an academic plan, because I’ve got all of this stuff going on.”

“They were basically like, no, because it’s not you, it’s not a mental health condition, it’s not a physical condition that’s affecting you. So, they said I couldn’t get one. I did call up disability afterwards, and they were also like, no, that’s not how this works.

“It made me very hesitant to reach out if something was going on.”

Isabella was able to access a disability plan, after getting in contact with the Students’ Representative Council (SRC). She only found out about the SRC through word of mouth. Before this, she was not aware of any support services that the University could provide, and her special considerations applications were denied because she had “insufficient proof”.

This statement becomes laughably pathetic when one compares it to other universities, and their approach to supporting student carers.

In a comment to Honi, a University of Technology Sydney (UTS) spokesperson stated, “It is recognised that a carer’s responsibilities impact on all aspects of their life.” In 2019, UTS engaged directly with student carers to see how their institution could better support them — with these recommendations being implemented.

UTS has their own staff and students with caring responsibilities policy. Western Sydney University, has a whole page dedicated to student carers, clearing outlining the support options available to them. The Australian Catholic University already allows students who have significant caring responsibilities to access the same support as those with disabilities.

In the meantime, when you search “USyd student carers”, Google asks “do you mean: USyd student careers”.

While the University records a $298.5 million surplus, and management is looking to reduce five-day simple extensions to three-days, student carers navigate a complex environment — where their life hangs in the balance of someone else’s. Isabella spoke about how she had a very precarious schedule, and while it may be ok for now, if anything goes wrong, such as her sister needing another surgery, the whole thing topples. Sandra mentioned her anxieties around managing university should her dad’s condition deteriorate. Eva has had postgraduate options cut off after the birth of her child. She effectively has no option to extend her maternity leave should she fail to get childcare soon, because she risks losing her stipend as a result of having suspended 6 months for pregnancy related illness.

The University boasts that they support a wide range of activities to ensure “everyone is accepted and has equal opportunities when it comes to education and employment in our university.” But if the University of Sydney has a commitment to equal opportunities, then they must look to who misses out when student carers are not adequately supported.

As noted by Isabella, “there may be many young people with caring duties who may not even consider applying to university as they may not think there are accommodations available. Of those that do enter uni, there may be many who have dropped out entirely as they were not lucky enough to hear about carers joining disability services through word of mouth.

“[This] is what I and one of my sisters would have done.”

While individual lecturers and tutors can provide some help for carers in an institution that seems intent on forgetting them, Eva, Sandra and Isabella’s experiences highlight that individual goodwill is not enough to overcome the structural issues present in how the University engages with student carers.

The bureaucratic processes that students with additional caretaking responsibilities are offered at the University are clunky at best, and traumatic at worst. Another person who Honi spoke with, stated that her special considerations for the care work she was doing for her mum who was terminally ill didn’t get approved until after her mum had passed away. She then had to re-engage with the special considerations process to update them that she had died.

At seemingly every turn, the University of Sydney tells student carers that they do not belong here. Student carers are left isolated, their experience of tertiary education tarred by a structural lack of support. There is a cruel irony in the lack of care USyd shows towards student carers, to continue to not address the existence of student carers will lead to ongoing harm for these students.

The solutions to this issue must be made in consultation with student carers. Many solutions were proposed during Honi’s discussions — consolidating all information related to student carers on one, easily searchable webpage, allowing students to access academic plans, and making these flexible to carers and the different circumstances they appear in. Investing in the special considerations service, so that students aren’t stressed about if their application will be approved, ensuring that lectures continue to be recorded and uploaded online, with flexible class options, and encouraging opportunities for student carers to meet up and feel less isolated are all places to start.

The University of Sydney is actively not supporting student carers. This is a choice. Sandra, Isabella, Eva and countless others should not have had the experiences at the University that they had. Being a student carer is hard enough without having to fight for the right to access support. Student carers at USyd can only hope that the University does something to better support them — it is long overdue.

*Name has been changed.

Editors note: This article was updated to include the below information from the University.

SUPRA, the SRC, and the Young Carers Association were consulted in the University’s work towards carers being able to access academic plans, with this “aiming” to be implemented in Semester Two this year — as per University spokesperson.”