CW: This article contains mention of child sexual abuse and grooming.

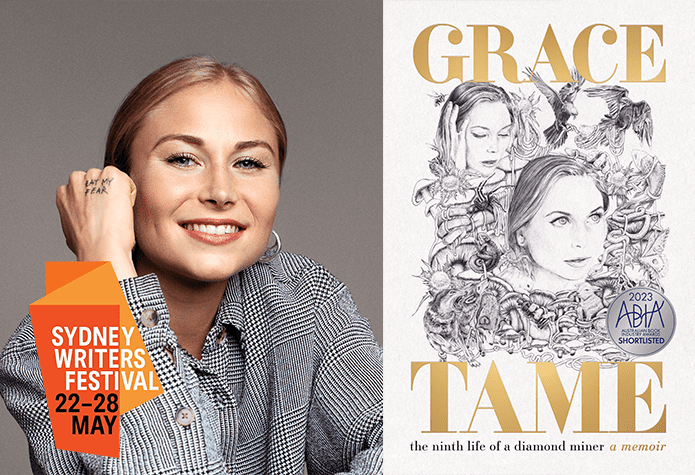

Grace Tame needs no introduction. After successfully advocating for a change in Tasmanian law which left her, and other sexual assault victim-survivors, unable to tell their stories to the media, Tame was recognised as Australian of the Year in 2021. Since then, Tame has altered the national conversation around child sexual assault and grooming, tackling abusers and the people and systems which enable them, and calling out their actions unflinchingly. Two years on, Tame’s memoir, The Ninth Life of a Diamond Miner, details her life so far, in a feat of storytelling that cements Tame not just as a phenomenal activist, speaker, and advocate, but author too.

The memoir outlines a life that the general public has come to know, through the media maelstrom that followed Tame throughout her work. As Tame told Honi, “I wasn’t born two years ago when you met me. I’ve been doing this [work] for about six years.” While the media narrative around Tame has been one note, the book is anything but. Tame writes of a life shaped by trauma, but by no means a life defined by it. Instead, a message of love, humour and connection — coexisting with, and overwhelming, the ongoing impacts of child sexual abuse and grooming — emerges.

Caitlin O’Keeffe-White: You speak so beautifully of your family and friends in this book, what does connection look like to you?

Grace Tame: I live for human connection. I live for bonding.

[My father’s family] connect a lot through humour and through shared interests. It’s very wholesome stuff. There’s banter where they can make fun of each other, but in a wholesome way. They bond through rich simplicity. My family on my mother’s side are like that too. There’s that rich simplicity of just being, not living in anticipation, which a lot of people do because we are existing in a capitalist society and capitalism by its very nature encourages you to be constantly in anticipation.

I do believe in the philosophy that a friend to everyone is a friend to no one. You can’t have loyalty if you are loyal to everyone. Not everyone, by virtue of difference, and distinction, and nuance, is going to get along. And that’s okay. Because we can have differences of opinions in lots of different areas, but we can still be civil to each other. There is also the need to have an awareness of the fact that some people are bad faith actors, and some people are actually not well intended, in their actions, in their words, in their decisions and you need to be able to recognize that. I’m autistic and so I tend to take everything at face value. I will have to often play a lot of catch up, in figuring out that some people who say that they’re on my side are not.

CW: How did writing the book differ from your work as Australian of the Year?

GT: When you are awarded Australian of the Year — they say it’s an award, not a role — you are booted onto this platform with very little prior awareness of what the circumstances are like. No one can be prepared for that. The program itself is not the only force that you are navigating, it’s a multi-directional operation in which you are sort of in the centre of. There’s this amorphous environment and lots of things happened that nobody could have predicted. Writing a book also became a part of that as well.

I look back on that book writing process, and it was very much marked by the actions of their child sex offender himself. We are in the middle of another criminal trial, the third criminal trial in 13 years. We allege that there were veiled threats that were being made to me on my social media platforms as well as to the foundation that my fiance was running. We were reporting these threats to Tasmania police as well as to the Australian Federal Police and we weren’t getting responses. We were spending a lot of time, [managing that] in that process of writing the book, which shouldn’t be a normal book writing process.

CW: There is a silence around child sexual abuse and grooming, despite it being so common. You have done so much to break this silence. Where do you want to see the most noise?

GT: I think that it’s time to let children and child protection be its own thing, and for child abuse victims to not be lumped in with adult victims for all crimes. Sexual abuse [as a child] is going to be different because somebody who hasn’t finished developing yet is going to have a different imprint than an adult. And when we keep lumping it in with adults, the adult’s kind of take the reins, they dominate the sphere, and it minimises the harm for children.

We need to separate somebody who’s not finished yet, to somebody who is.

—

In a moving passage in the book, Tame describes being on school holidays with two friends, when she learned that the details of her abuse had been made public in a newspaper. The crimes of child grooming, rape, and sexual abuse had disgustingly been (mis)represented as an “affair”.

She called the journalist up. It would mark a clear lineation in the media representation of Tame — one riddled with the self-interest of major organisations, moving from her clear message, of stopping child sexual abuse and raising awareness of the complexities of grooming, to cheap chat about facial expressions and so-called “social propriety” designed to register revenue. Tame is clear about this too.

CW: It is obvious that the media has failed in multiple different ways when talking to, and of, you and about child sexual abuse broadly. How can they be better?

GT: You would need to restructure the whole model of media as we know it. Because what you have got is this capitalist structure, and if you look at the mainstream media, and even some independent media, the market share is not very diverse. It’s supposed to communicate unbiased information from one source to the masses, and we put our trust in that.

But you’ve got a very small pool of influence that has a lot of sway. And then the few outside of that are a bit gun shy because of that.

That hegemony of the Politico Media complex, is also interdependent on the hegemony of white supremacy, of very powerful religious groups, like the Catholic Church, and then you’ve also got, I want to say the patriarchy, although I’m personally not somebody who tends to align with feminism, even though I believe it principally.

But you’ve got those hegemonies all working together. [They] suppress information within these spheres — and this is information that is documented within scientific circles. About the effects of cigarettes on the human body, that it caused cancer and all myriad diseases. Also, the effects of greenhouse gases. These are the same forces. It’s got nothing to do with politics, but they’ve made it about politics.

So what you would have to do is you’d have to start again. Tear it all down. It’s not going to change.

CW: Where do you find hope in all that?

GT: You put it out there.

—

Grace Tame has undoubtedly achieved putting hope out there — indeed, her memoir is another iteration of this. The Ninth Life of a Diamond Miner details a life where, at every turn, there is failure of institutions — a school that ignored ongoing reports of a teacher’s misconduct, a media landscape that values clicks more than truth, a legal system that doesn’t fully recognise the severity and long-term impacts of grooming on survivors, and indeed the Australian government itself, who threw Tame into the national spotlight with minimal support.

These failures are glaring, but what emerges stronger than that is a love of people, stories and comedy. One walks away from reading this memoir with the realisation that Grace Tame is a powerhouse of a human. The Ninth Life of a Diamond Miner strikes a balance that few memoirs have been able to achieve — it never shies away from the trauma that Tame has survived, but looks at what comprises a life, and examines this honestly and with a wonderfully wicked sense of humour. Inside jokes among mates, family lore, Monty Python references, and John le Carré thrillers, are weaved throughout it. Tame even joked in the interview: “I think of everything now in terms of book length. 800 words, no I want 8000 words.” I think most who have read this book would look forward to whatever Tame writes next.

You can see Grace Tame speak at Sydney Writers Festival, at the Real Selves panel, alongside Chloe Hayden, Sasha Kutabah Sarago and Hannah Diveny, on Saturday, May 27, at 7:30pm. Tame’s book, The Ninth Life of a Diamond Miner, is out now.

Helplines:

Lifeline – 13 11 14

Kids Helpline (available to people between the ages of 5 – 25) – 1800 55 1800

1800 RESPECT – 1800 737 732