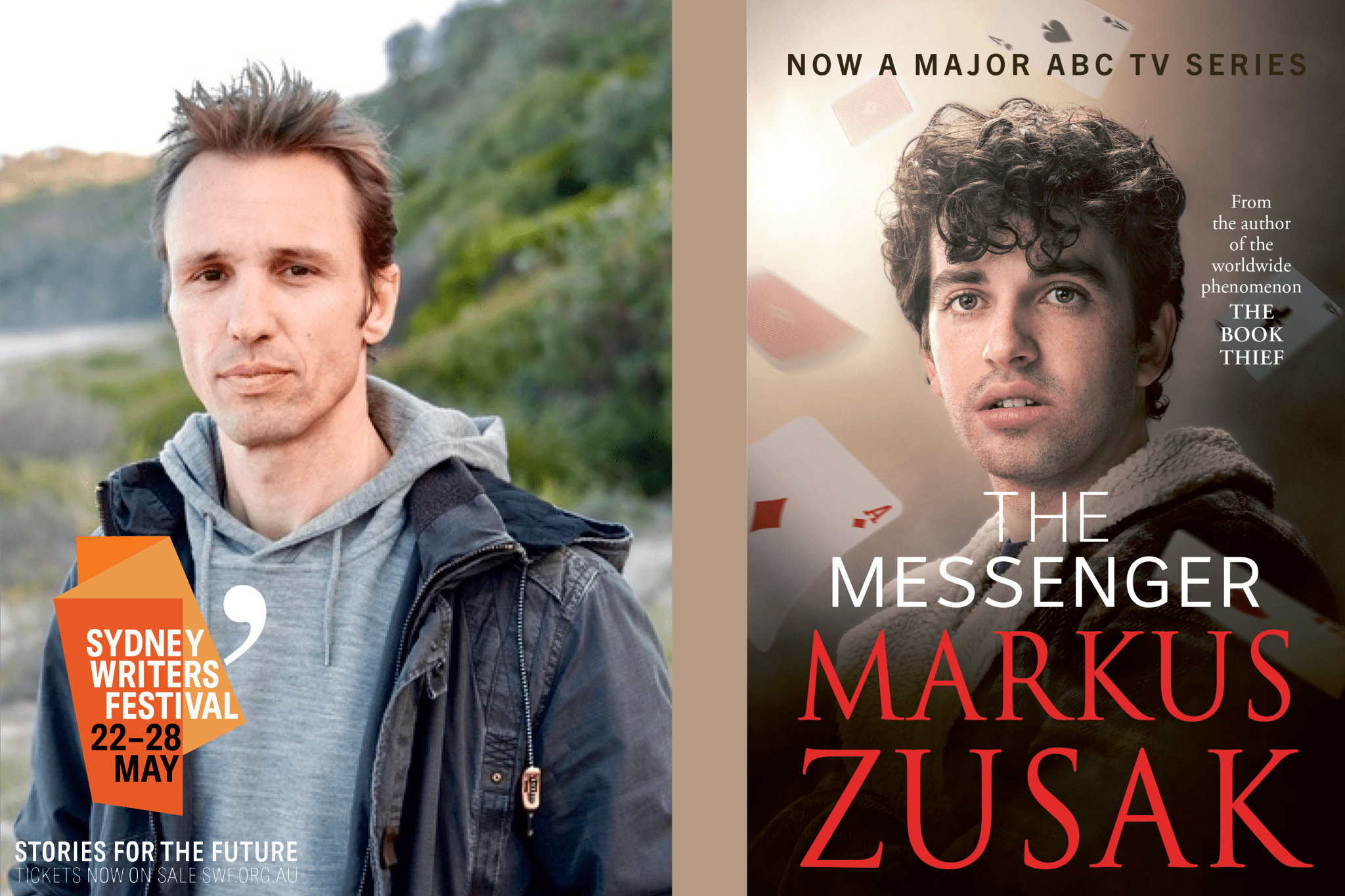

Most authors at the Sydney Writers’ Festival are there to discuss their most recently published work. They discuss the intricacies of the writing process and show off their glossy new release. Markus Zusak, on the other hand, is speaking this year about a different kind of process – the process of translating his 2002 novel, The Messenger, into an eight-part television series. The Messenger centres on accidental hero Ed Kennedy, and his complex journey of personal growth, punctuated by acts of kindness towards others.

Markus Zusak is an award-winning Australian author best known for his international bestseller The Book Thief, which has since been turned into an Academy Award nominated film; our conversation, however, centred on the earlier novel, The Messenger. Although I was unfortunately unable to sit down with the novelist in person, our email correspondence covered quite a lot of ground, and Zusak carefully shed light on his process.

- From Page to Screen

Alexandra Dent: What surprised you the most when translating The Messenger from novel to screen?

Markus Zusak: First and foremost, it’s that it was made. That’s always what surprises the author of the book, because we all know how hard it is for movies and TV shows to be produced. So many books are optioned but a small percentage make it to the screen. Extra surprising in this case is that the TV series is coming out twenty-one years after the book was published. It just shows that hanging in can give you a reward well after the work is done.

AD: What did you gain from your position as executive producer for the show? How involved were you in the process and how did it differ from writing a novel?

MZ: I still took a fairly hands-off approach. It was mainly in the earliest stages of deciding how we wanted the series to feel, and retaining the heart of the book. I was mostly involved by reading scripts as they came in. Sarah Lambert and Kirsty Fisher were the two main writers, and their work is outstanding, so that part was easy. I would read each script as it came in and pretty much just relax. I think when you’re writing a novel you get to colour the artwork in, whereas a screenwriter needs to trust what the director and the cast and crew will bring to it. I feel like when you’re writing a novel, you get to control everything. Maybe that’s why I chose writing books…

AD: Your 2005 novel The Book Thief was translated to screen in 2013. What did you find unique about storytelling through a television series as opposed to film?

MZ: I loved one aspect in particular, and that’s that across eight episodes, the writers were able to make the world of The Messenger both bigger and deeper. They expanded on the novel, rather than having to break it down to movie-length. The most exciting element in that sense was that Sarah, Kirsty and the other writers were able to play. There’s a beautiful quirkiness in the series, and characters grow bigger from out of the pages of the book.

- The Writing Process

AD: How much of your fiction is based on fact? What would you say are the difficulties that arise when using aspects of your real life as material for novels?

MZ: I have to say it’s less of a hassle than people think, because by the time you’ve used something from real life in a book, it’s usually unrecognisable with everything else that goes on around it. Almost no-one has ever recognised themselves in any of my novels. Also, it’s usually just tiny details or moments.

AD: What are the main aspects you consider when developing characters? How do you create characters that feel so familiar and complex?

MZ: It’s a bit like building a brick wall, rather than an art form (at least for me). I consider myself a tradesman, trying to build a wall that has exactly the right number of bricks. Too many and it falls from the weight. Too few and there are holes for the wind to come through. All I’m ever trying to do when I write is to feel like I’m there – to believe it while I’m in it, so I just keep building till I feel like the job is done.

AD: What does a day in your life look like, and how do you make time to write?

MZ: It looks like early mornings, dog walks, laughing and arguing in the kitchen with my family, and making sure (or at least trying) to get to my desk at the same time every day. I’m distractible like everyone else, but when I write I turn off devices. A lot can be done in even half an hour if you turn the rest of the world off. We all have priorities in our lives, and I just try to be honest about where writing sits on that list. Sometimes we tell ourselves how dedicated we are to something, and then we have to ask, “Okay, so why was that number 11 on the list of things I did today?” I’m guilty of trying to clear a whole lot of tasks before I start work – but sometimes you have to say, ‘No, not today. Today I have to let things go so I do what I’m really supposed to be doing.’

AD: How do you deal with times where you really can’t bring yourself to put pen to paper

MZ: As you can tell, I can be easily distracted. There’s no shortage of jobs to be done – I usually do some work in the backyard. At least that way I feel like I got something accomplished that day.

AD: Who are your main influences? This isn’t restricted to literature! What music/films/people inspire you the most?

MZ: There are literally hundreds of answers to this. I tend to become obsessive with books, movies and music. If I love something, I’ll reread it many times. I’m not trying to decode how the author has pulled off what they’ve done, but I somehow gain an understanding by experiencing it again. The last book I reread (for the third time) was Tobias Wolff’s great short novel, Old School. It’s such a unique book, especially when you hit the last twenty or thirty pages.

- On the Sydney Writers’ Festival

AD: The Sydney Writers’ Festival theme this year is “stories for the future”. What does this mean to you and how do you envision the future of literature? What excites you and what scares you?

MZ: I think as a writer, we all want to write something that stands the test of time, and I guess that only happens by putting all the toil and worry into what we’re working on now. And then you can only hope. The book has to do the rest.

AD: How do you envision the future of literature? What excites you and what scares you?

MZ: I actually don’t concern myself with that. Of course I worry when I stand at Central or Town Hall Station and see 300 people glued to their phones – but that’s when I pull out a book. Pretty daring, I know!

AD: What advice do you have for the next generation of authors?

MZ: Do the work, accept failure as one of the best and most necessary parts of the job. Ask yourself if you’d want to write even if a ray of light came out of the sky and said, ‘Nothing you write will ever be published’. If the answer is yes, you’re a writer.

Markus will be speaking at the Sydney Writers’ Festival at Carriageworks in Eveleigh. He will be in conversation at Markus Zusak: Bringing The Messenger to the Screen, at 3pm on Thursday 25 May.