CW: This piece discusses sexual assault, harassment and hazing.

Calls to abolish the USyd Residential Colleges have been made for years. Activists has repeatedly spoken out about the pervasive nature of sexual violence on campus, particularly in the Colleges. Reports have been investigated and released. Victim survivors have shared their experiences. And yet, very little has changed.

In 2016, following media attention that highlighted the systemic and sustained nature of sexual violence at the Colleges, then-Vice Chancellor Michael Spence dangled a so-called “nuclear option” over the Colleges’ heads. He threatened to disaffiliate the colleges and take back their land, effectively abolishing them, to convince them to cooperate with the Broderick report. Michael Spence admitted that the “deep contempt for women” at St Pauls was a “profound issue in the life of the College, going to its very licence to operate.”

Despite the lack of follow through, this shows that it is very possible to dismantle, if not abolish, the Colleges. The Women’s Collective has been calling for the abolition of the Colleges, and to replace it with safe and actually affordable student housing, for years now.

Over the years, multiple reports have attempted to investigate the state of sexual assault on campus. The latest in these attempts is the recently released inaugural sexual misconduct report, which did not achieve very much for women and other sexual minorities at the University of Sydney. Framed as only the first step in a continuing effort for transparency from management, the report differs significantly from other data collected about the prevalence of sexual violence at universities.

At its core, it was not a data-collecting exercise. Data was collated from the complaints process, a form through which victims of sexual assault or harrassment can seek recourse against a perpetrator. This form is buried on the University of Sydney’s online site, and can be quite alienating for individuals making a disclosure. By its very nature, this data does not represent the entirety of the problem of sexual assault at USyd. Instead, it can only represent the experiences of the people who firstly knew that the form existed, and then were able to navigate the form itself.

Activists at USyd have criticised the failure of University Management to sufficiently increase accessibility for, and engagement with, their sexual misconduct reporting system, particularly highlighting the “gag clause” in the University’s sexual misconduct policy. The Student Sexual Misconduct Policy at the University of Sydney specifically outlines that students must “keep confidential” details about the identity of the perpetrator, the incident itself and the fact that a report was filed. If a student is found to have breached this confidentiality requirement, they could be subject to student misconduct penalties from Management.

Out of 121 disclosures made to the University in 2022, only 23 were complaints. Only 7 were either resolved through assisted resolution or had a misconduct penalty applied to the respondent. Despite the report’s supposed commitment to transparency, it does not share anything about the outcomes of the process nor details about the context of incidents. This can be included without breaching the privacy of survivors, but it wasn’t.

This is a common thread throughout the reporting process at universities across Australia. The Senate Committee investigating current and proposed sexual consent laws in Australia recently released a report detailing not only the legislation surrounding consent but also the preventative measures and reporting processes for complaints of sexual assault. The report makes significant mention of existing university procedures and responses.

The Senate Committee has recently received submissions about the inadequacy of current measures and processes. One such submission from Nina Funnell, a director at End Rape on Campus (EROC), referenced data obtained by Channel 7 in 2017. They found that out of 565 formal complaints across 39 universities, only six resulted in expulsion. In one incident where a perpetrator admitted guilt, they were charged a fine of $55 — at a university where a parking ticket was more expensive.

End Rape on Campus co-founder Sharna Bremner works with students who make disclosures to their universities, and has repeatedly found that universities do not provide adequate support to students. “A really common theme among the students we’ve supported over the last eight/nine years now is, ‘My rape was bad, but the way my university responded was worse’.”

The Senate Committee’s report is a pulse-check on an issue that impacts far too many students across Australia. It makes significant recommendations aimed at preventing sexual violence, from implementing Respectful Relationships Education throughout the Australian curriculum to supporting survivors at University.

The National Student Safety Survey has occurred once, in 2021. The Senate Committee is calling on Universities Australia to commit to holding the survey every three years. Advocates have been critical of the report, as the data obtained in 2021 was not a true reflection of sexual violence at universities. Only 30% of the University population (those living at on-campus residences) were physically attending university due to extended COVID lockdowns.

Advocates have also been calling on the government to form an independent task force with the power to impose meaningful sanctions on universities who fail to meet minimum standards in their response to sexual assault on campus. End Rape on Campus penned an open letter to the Albanese government in July calling for such a task force, to be composed of experts in the field of sexual violence and with the power to enforce their directives. Student advocacy groups, including the Women’s Collective, have signed off on this document, and the Senate Committee is calling for its implementation as part of their report.

Dr Allison Henry, a postdoctoral Research Fellow with the Australian Human Rights commission, said that “progress has stalled due to an overreliance on the self-regulating university sector”. The Universities Accord Interim Report also found that governance at Universities is lacking, leaving victims of sexual assault and harrassment unsupported. Jason Clare, Federal Minister for Education, has also announced that he will be working with state and territory governments to improve governance at universities. This is not enough, even if it might act as a first step towards accountability for universities.

TEQSA was initially tasked with responding to the findings of the Australian Human Rights Commission’s Change the Course Report. The report found that there is a need for “a strong and visible commitment to action from university leaders, accompanied by clear and transparent implementation of these recommendations.” Particularly as TEQSA has failed to enforce Threshold Standards, which are requirements for registration as a higher education provider, in the fields of wellbeing, safety, student grievance and complaint.

Not a single university was found to be non-compliant with Threshold Standards in the wake of the Change the Course report, and TEQSA has not applied sanctions beyond monitoring and reporting on several universities. TEQSA does not have the power to implement more severe sanctions, and is therefore unsuited to the task of enforcing these standards.

The Senate Committee’s report calls upon the government to do a review of TEQSA’s suitability for the task of holding universities to account when it comes to sexual assault. Due to the lack of sanctions applied to universities, this task may be better delegated to a task force with more concrete powers and specialist advisors.

One of the most appalling findings of the Senate Committee’s report was that Universities Australia will not be continuing with development of a campaign to raise awareness about sexual assault at a tertiary level. Universities Australia was awarded a grant in 2021 and began testing materials for the campaign, with materials from the Department of Social Services stating that the campaign was able to “successfully communicate the overarching message” in September 2021.

In November 2021, Our Watch, one of the campaign’s expert advisors, was informed that it was put on hold, and the DSS was advised of various Vice Chancellor’s views on the campaign. Universities Australia received $1.5 million from the government to institute this program.

In June 2022, Universities Australia told the DSS that the campaign “was not viable to be rolled out”, seemingly as a result of the Vice Chancellor’s feedback. Despite this, the Department maintained the contract and pivoted to a good practice guide. Our Watch created a similar guide, however Universities Australia maintains that theirs is different. Universities Australia conceded that the National Union of Students was not consulted in the development of the guide.

There is a wealth of literature outlining the prevalence of sexual violence on campus, pioneered particularly by the work of women’s collectives and women’s officers at various universities. The Red Zone Report, in particular, is the gold standard for understanding the scale of sexual violence on campus.

The Red Zone Report was a response to the entirely inadequate Broderick report, which was commissioned by the University of Sydney as a result of sustained media attention for the Residential Colleges at the University. What began as a single news story in Pulp’s previous iteration, Pulp Media, then evolved into a feature from a college resident in Honi Soit. The two women who broke these stories, Aparna Balakumar from Pulp and Justine Landis-Hanley from Honi, were instrumental in establishing the desperate need for a review into rape culture at the colleges.

Cultural renewal at the University of Sydney residential colleges, informally known as the Broderick Report, did not deliver what it needed to. Elizabeth Broderick, a former sex discrimination commissioner, was approached by both the Colleges, except St Paul’s, and University management as part of commissioning the report. Submissions to the report were sourced internally, with interviews taking place in a group setting. Students of the Colleges at the University of Sydney are notoriously insular and protective of their media reputation. Through traditions such as hazing, a hierarchy is established within which people are ostracised if they deviate from acceptable behaviour. Landis-Hanley experienced this first hand when following the publication of her story in Honi, members of Sancta Sophia would not talk to her or look at her during meal times.

As such, it is unconvincing that students would have felt able to share their views on the systems of privilege and entitlement that support the colleges in a group setting. The review also takes on the broad subject of “culture” at the colleges, rather than tackling the issue of sexual assault head-on. Of more than 150 quotes used in the report, more than 100 are from students who report that they enjoyed their time at college. It has been extensively criticised by activists for its content and structure, as well as the flawed methodology used to obtain the results.

The Red Zone Report, by comparison, is the culmination of 8 weeks of unpaid labor from lead author Nina Funnell, co-author Anna Hush and research assistant Sharna Bremner. They took on the seemingly insurmountable task of documenting the horrific abuse faced by students, particularly women and gender minorities, at residential colleges at the University of Sydney.

The report situated the colleges within their history of misconduct, providing a timeline of newspaper reports, Facebook posts and student activist campaigns to illustrate the entrenched disregard for women. It is a truly horrific read.

The Red Zone Report particularly details the intense rituals involved in hazing. There are many examples of older students inflicting cruelty on “freshers” to initiate them into a culture where consent and boundaries are of no consequence. It is a self perpetuating cycle, in which those subjected to such cruelty look forward to inflicting the same onto those younger than them.

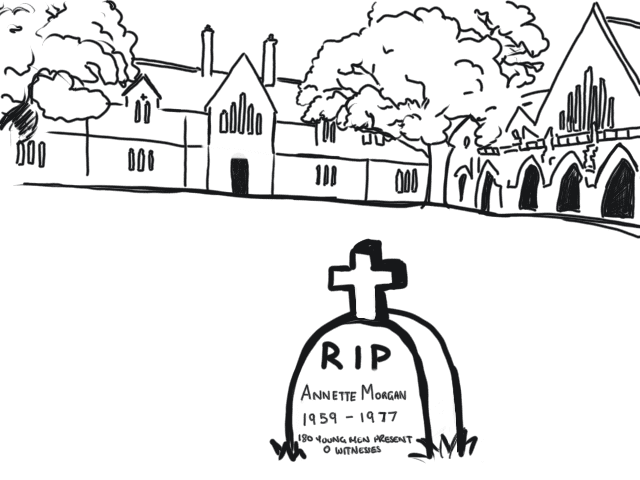

Her body was discovered undressed and “bashed” on St Paul’s College Oval on August 17, 1977. Annette’s death sparked protests and outrage, but the case remains unsolved to this day.

Art by Liset Campos Manrique.

Just a handful of incidents recorded in the Red Zone Report include St Andrew’s students advertising their 1993 formal with slogans such as “ride them home and drop your load” and “buck your girl”, a pro-rape Facebook group made by students associated with St. Paul’s in 2009, and Wesley College’s 2016 yearbook featuring ‘Rackweb’ which documented who students in the College had slept with. ‘Freshers’ were judged “primarily for… [their] willingness to put out for their seniors” and for “enabling all the hook-ups a sleazy, pussy hungry-adolescent could dream of.” Incidents such as these are a fact of daily life in the Colleges, and continue to be.

There are many problems within the colleges that entrench such behaviour. The existence of a powerful alumni within the governance system prevents the prohibition of traditions such as hazing. The hierarchy imposed by such rituals creates a dangerous disregard for one’s own body, and by extension, the bodies of others. The sense of entitlement and insularity that comes from participating in an institution with a prestigious history, one which is pitted against those outside the colleges calling for their abolition.

Most worrying is that there is no way to measure the amount of sexual assault that occurs at the Colleges. Student accommodation is grouped with the colleges for the NSSS results and colleges do not provide their own data. Students are inherently encouraged to keep quiet about their assault due to the culture of slut shaming and victim blaming that pervades colleges. That is why the only solution is abolition: because wherever there are colleges, students will not be safe.

With the scope of sexual violence as broad as it is today, abolishing the colleges is one necessary step towards creating a safe campus. Colleges are a relic of the university’s past: they serve only to empower the rich. Many say that they feel an extreme sense of belonging in their colleges, however this belonging is contingent on participating in a culture that blatantly disregards women and sees collegians as a superior group compared to what they call “day rats”.

Abolition of the Colleges is more important now than ever before. As we see a return to campus for the vast majority of students, those in colleges remained in their residences throughout the COVID pandemic. With a myriad of scandals involving partying and gathering throughout the lockdowns, the entitlement that collegians feel is clear. In a cost of living crisis, the sandstone buildings would be better suited to housing low-income students than sequestering the rich in their ivory towers.

Grave reads: RIP Annette Morgan, 1959-1977. 180 young men present. 0 Witnesses.