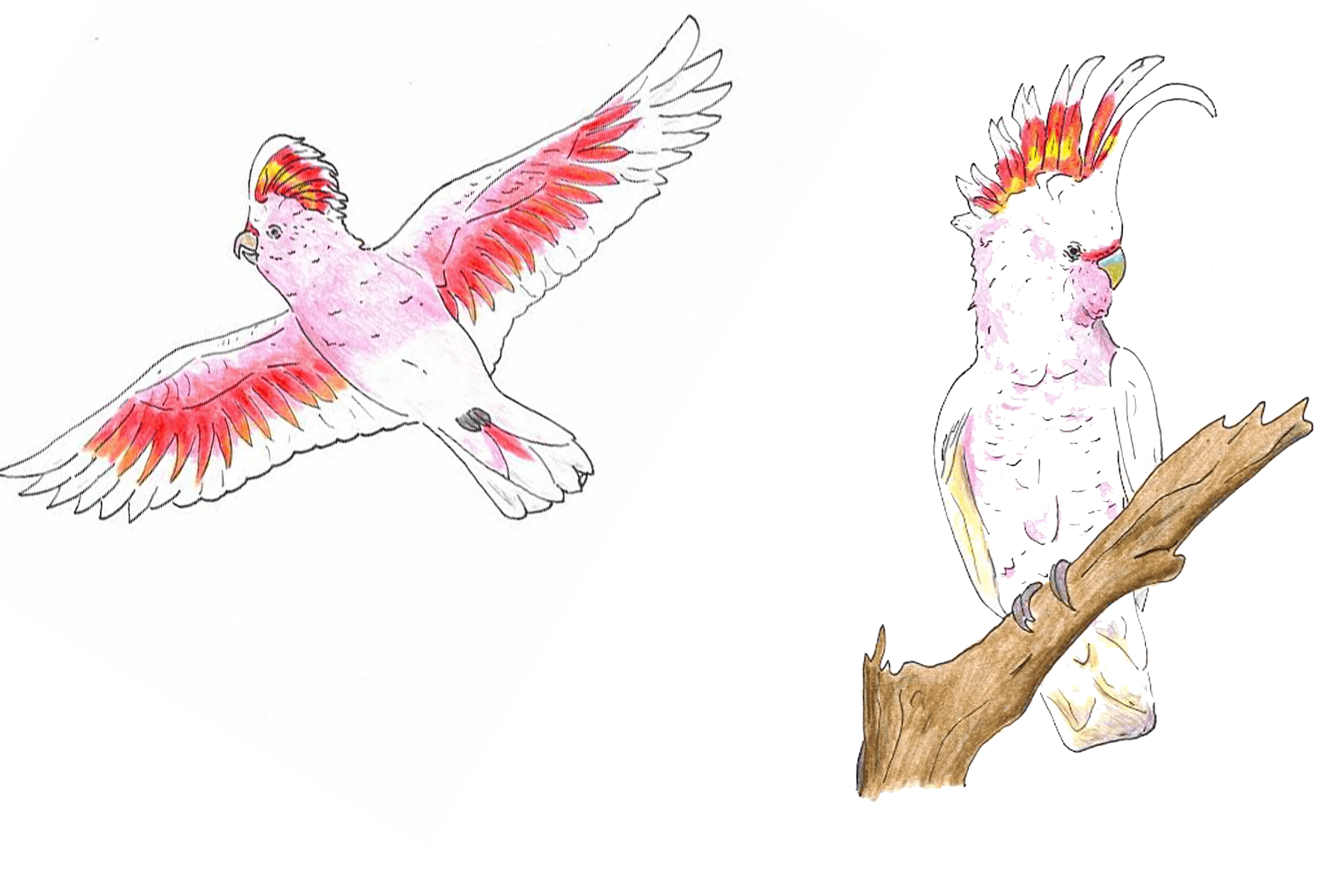

In January 2022, the desert between Broken Hill and Menindee, in far Western NSW, was a landscape transformed from orange to green. From the passenger seat, I watched a verdant blanket unfold beneath scraggly sloping hills. Amongst the bountiful emerald grass and blue saltbush strode huge gaggles of emu. But it was at the sight of a different bird that I yelled “stop the car!” As I wound down the window, a breeze glided between overcast skies and the thirst-sated earth, carrying with it an eerie, high-pitched chortle. A cluster of pastel pink birds — almost white at this distance — sat on the gidgee branches, a gang of ghostly figures. And then it happened; a crest shot from an otherwise bland head — a flash of fluorescent orange and yellow, unnatural in its striking shade. This was the first time I’d ever seen a Pink Cockatoo in the flesh, one of our most beautiful, enigmatic native birds.

The Pink Cockatoo, like any animal in a colonised environment, has many names. The Wiradjuri people of western NSW call it wijugla, whilst John Gould recorded the name jakkulyakkul in Western Australia. Kokatha people of the South Australian Western Desert call the bird kikkalulla, whilst Arrernte call it nkuna and ungkuna. The Pitjantjatjara name — a language group of Central Australia — for the Pink Cockatoo is kakalyalya. The word Cockatoo itself has a long history too, emerging in Dutch as kaketoe in the 1610s. This itself was likely borrowed from the Malay word kakatua. The bird’s scientific name is Lophochroa leadbeateri, positioning it as the lone species within its genus — although more closely related to basal Cacatua Cockatoos (your standard crested types) than the Galah, which sits alone in the genus Eolophus. Common names in English for the Pink Cockatoo have a complicated history. Pink Cockatoo was actually an early common name ascribed to the bird, and is visible in the 1926 official documentation of the Royal Australian Ornithological Union (RAOU). Pink Cockatoo was only beaten by John Gould’s original name of Leadbeater’s Cockatoo — named after Benjamin Leadbeater, an English naturalist. The other name commonly associated with the bird — and still labelled as such by the NSW Government’s official website on the animal — is the Major Mitchell’s Cockatoo.

By July 2022, the desert at Lake Mungo, in far south-western NSW, still exhibited the signs of the rain that had drenched areas of the interior since the severe drought of 2019 ended. The low, flat pan of the ancient lake, dry since the end of the Ice Age 10,000 years ago, lay draped in a coat of thriving saltbush, punctuated by little muted-red flowers. Following a winding historical walk into the dunes on the western end of the lake, opposite the famous Walls of China, we walked into a wood of native Cypress. Admiring the whirling bodies of long-dead trees standing amidst the relatively lush new growth, I heard that familiar, esoteric chortle. There! Two Pink Cockatoos raced by above the crest of the dune, flashing their brilliant orange-pink underwings. It was a glimpse that set my heart racing, a special excitement that welled through my diaphragm and emerged to make my day.

Major Thomas Mitchell didn’t name the bird after himself — his notes call it the Red-top Cockatoo. However, it was the excited way in which he described the animal that inspired the renaming of the bird in 1977. Mitchell wrote that “Few birds more enliven the monotonous hues of the Australian forest than this beautiful species whose pink-coloured wings and flowing crest might have embellished the air of a more voluptuous region.” It was a poll of the membership of the then RAOU that fixed on the name Major Mitchell’s Cockatoo. Unsurprisingly, Mitchell himself was a less-than-savoury figure. In 1836, Mitchell — an “explorer” of the Australian interior — directed a massacre of Kureinji and Barkindji people on the Murray River. Because of growing awareness of the Frontier Wars in Australia, and a necessary examination of our national history, BirdLife Australia has recently officially reverted to Pink Cockatoo as the name for this beautiful animal. Names are an important vehicle through which colonisation operates: the renaming of organisms by white settler scientists, and more broadly societies, forces the natural world within Imperialist ideologies of discovery. By picking a new name, settler-societies deny the presence of an old name, and positions themselves as the original “discoverers”. In particular, the naming of organisms after colonial “heroes” lionises these figures within such mythologies, and associates organisms that are culturally important, aesthetically beautiful and intrinsically valuable, with brutal dispossession, violence and murder. “Pink Cockatoo” may not be a First Nations’ name (of which, due to the regional diversity of First Nations’ language, there are many), but it is a start.

The carpark at Kwatatuma-Ormiston Gorge sits beneath one of these bestubbled rock faces, with a gravel path twisting into yellow scrub towards the famous waterhole. It was walking this path, in December 2022, that I saw a brilliant flash of white. Looking up, I was struck to be surrounded by a crowd of Pink Cockatoos, watching me from intelligent eyes. My chest swelled with pure gratitude as a particular individual allowed me to stand and watch (at a safe and respectful distance) as it contemplated me from a bobbing black branch. My solitary mind buzzed with a single plea: give me a look at that exquisite crest. After a photograph framed by the rock face, she obliged. Before joining the rest of her flock, who by now were flying in pairs towards the eucalypt grove that marked the opening of the gorge, she flashed her brilliant orange-and-yellow crest and took flight.

The publicity associated with this renaming could not come at a more pressing moment. Just this year, the Pink Cockatoo was added to the threatened species list. Unlike some other species, Pink Cockatoos have not benefited from the clearing of Australian bush for agriculture and pastoralism. They are a desert bird, rarely seen outside the arid interior of our vast continent, and so incapable of reaping the benefits of urban areas that their relatives have exploited. Furthermore, Pink Cockatoos will not nest near other Pink Cockatoos, meaning their reproductive cycle is uniquely affected by the fragmentation of habitat associated with colonisation. If this species is to survive, like the hundreds of Australian species at risk of extinction, we must all recognise its intrinsic value, environmental importance, cultural significance, and exquisite beauty. It would be a tragedy to lose the Pink Cockatoo, one of our most ethereal birds, and a symbol of the rugged, understated beauty of the Australian interior.