Syntropic farming has been gaining traction in recent decades as a way to more effectively grow produce on land, especially in areas where farming has been previously thought to be impossible.

The approach holds itself more as a set of perspectives on sustainable growing, rather than a one-size-fits-all recipe for agricultural success. It was popularised by farmer and researcher Ernst Gotsch, who has been operating a farm in Brazil since the 1980s using syntropic farming principles. Within a few years of starting this project he was able to turn his land, which used to be known as having “the poorest quality soil in the region”, into a lush ecosystem that has a similar soil quality to that of natural rainforests. On top of this, his farm currently yields over 1,000 kilograms of cocoa per hectare, much higher than Brazil’s national average of less than 400 kilograms in the same area.

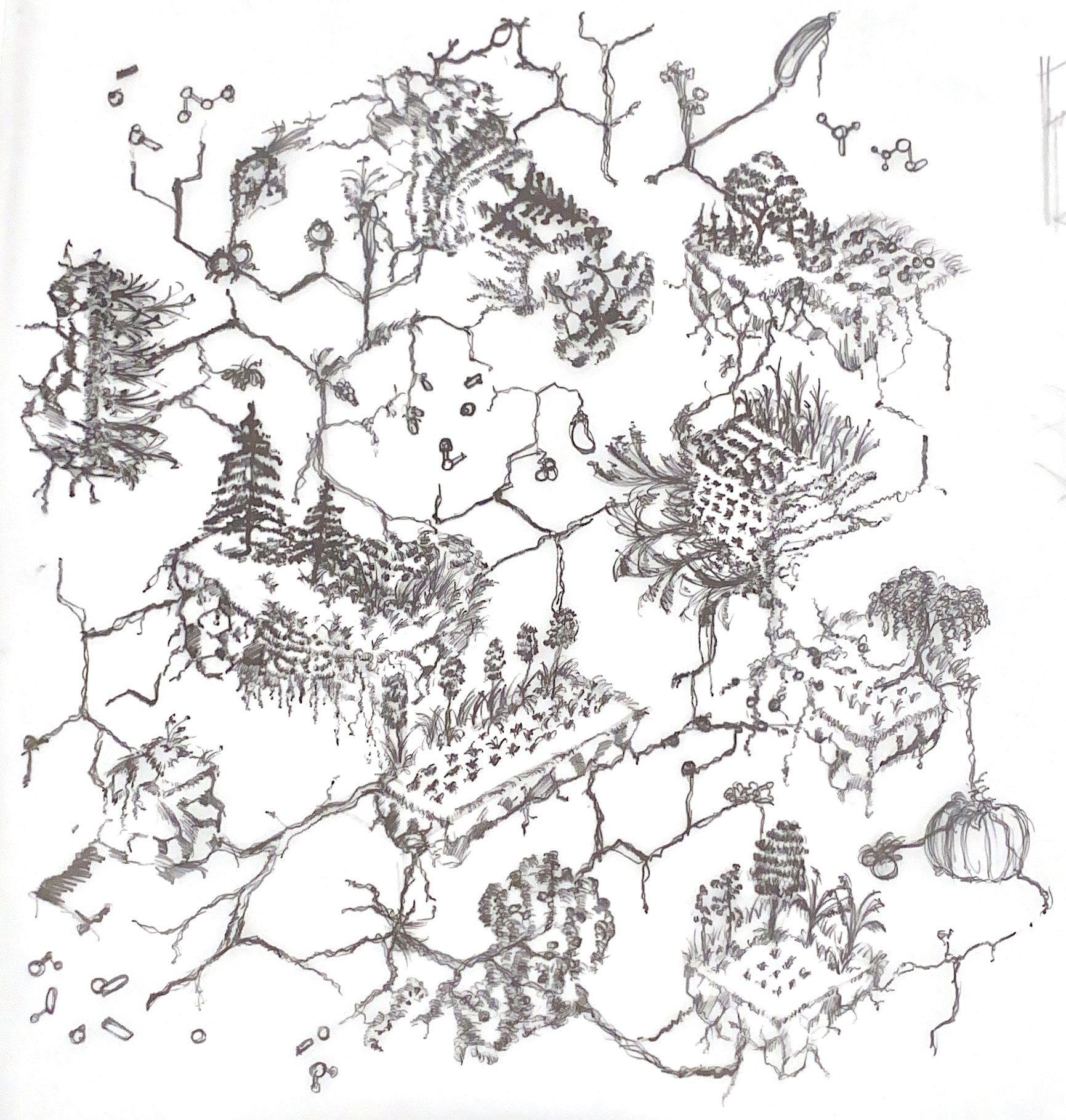

The key to syntropic farming’s success is its focus on trying to build a whole ecosystem, wherein plants thrive and fulfil their needs through their symbiotic relationships with each other, rather than a more traditional farming approach that focuses on the needs of each plant or species individually. Syntropic farming uses sequential cycles to build up this ecosystem, with each cycle creating a more fertile environment able to support more complex plant species.

Take, for example, an arid landscape, filled with rock-hard, sun-baked soil, unable to retain moisture or nutrients and therefore only able to sustain the hardiest of plants. You could try to brute-force a plantation of fruit trees in these conditions, but this would require hours of labour supplying these trees with external resources necessary for their growth that the soil currently cannot provide them with, ultimately with a minimal likelihood of success.

A syntropic approach to this would instead plant species that are already able to thrive in these tough conditions — shrubs and grasses, for example, and after they have taken hold, use the more nutrient-rich soil these plants provide to grow plants that need more nutrients in the soil to thrive. Through continuing these cycles, you plant more complex and larger plants, until you have eventually created an environment that supports your goal of fruit trees. In this way, syntropic farming leverages the plants that you can currently grow into creating an environment that allows you to successfully plant what you want to grow.

Syntropic farming has found success all over the world, from being used for the Great Green Wall project in Africa to stop the expansion of the Sahara Desert, to local farms in tropical Haiti, orange tree systems in Bolivia, and research farms in the Mediterranean. In Australia, one of the foremost syntropic farms that exists is at The Hungry Spirit in Lightning Ridge.

The Hungry Spirit turned to syntropic farming in June of 2020 to try to reinvigorate land that was devastated by the effects of frequent droughts and little rainfall during the 2010s. This technique has allowed them to be able to successfully grow food for themselves and their business in a semi-arid climate, and they have since expanded with more syntropic systems.

In a comment for Honi Soit, Rebel Black, one of the owners of The Hungry Spirit, said the amount of interest her syntropic farming has generated has been one of the best positive effects it has had. Another unexpected benefit of her syntropic systems is the micro climate it has created around her property, “The greenery really feels incredible, especially during [the] long hot summer.”

Despite this, syntropic farming does also have its fair share of challenges. It takes time, often years, for the desired outcomes of syntropic systems to come into effect, and as usual with a new method, creating a syntropic system involves a lot of trial and error, especially with the limited amounts of research undertaken on it so far. Finding the right mix of plants that work for the climate your farm is in can be difficult, along with the complexities involved with figuring out when and where to plant them in the highly structured syntropic system. Syntropic farming also isn’t immune to natural weather events, Black told Honi that ‘plant loss due to extreme heat and frost’ has also affected her farm, which requires complex workarounds to still make her farms work.

Despite its flaws, syntropic farming has vast benefits in being a system that replicates nature, rather than overtaking it. An ecosystem that can sustain itself, and is further able to provide us with food and tools on top of this, seems like a golden ideal for what farming can be.