The argument that the Voice is “divisive” is confusing. But it’s working. Perhaps that’s the point.

When Voice opponents claim that the advisory body is “divisive” they make, I think, two separate claims: first, that the Voice is “divisive” in the sense that it is “polarising” or corrosive to national unity. Essentially, the harm of the Voice here is in people disagreeing. Second, that the Voice is “racially divisive”, in the sense that First Nations people should not be “treated differently”, or at least not in the Constitution.

The national unity, or polarisation, argument is clearly weak.

Perhaps there could exist some proposals which are intentionally designed, or are so likely to lead to harmful disagreement. But it is hard to see how the Voice is one of those. At no point have anti-Voice campaigners pointed to evidence that the Voice proposal is one which is deliberately aimed at dividing the nation through beginning some sort of culture war. Indeed, the opposite is true. The makers of the Uluru Statement from the Heart have invariably framed the Voice as an “invitation” or “reaching out” to White Australia. Even a cynical political analysis as to why the Albanese government is putting the Voice to a referendum leads to the conclusion that the Voice is not designed to be divisive: Labor put the Voice to a referendum because they thought that it could win, and in doing so create the kind of productive “national conversation” which would provide the blue-print to proceed with further changes beyond an unambitious first-term policy platform.

Moreover, it is hard to see why the Voice is so likely to lead to harmful disagreement. It proposes a modest change: to establish a non-binding advisory body to recognise First Nations people in the Constitution. It has the support of 83% of First Nations people, leaders of both sides of politics, NGOs and broad swathes of corporate Australia. The federal Coalition also supports Constitutional recognition, and the legislative establishment of the Voice. In doing so, they implicitly accept the Voice’s value. Why is combining Constitutional recognition and a Voice so divisive?

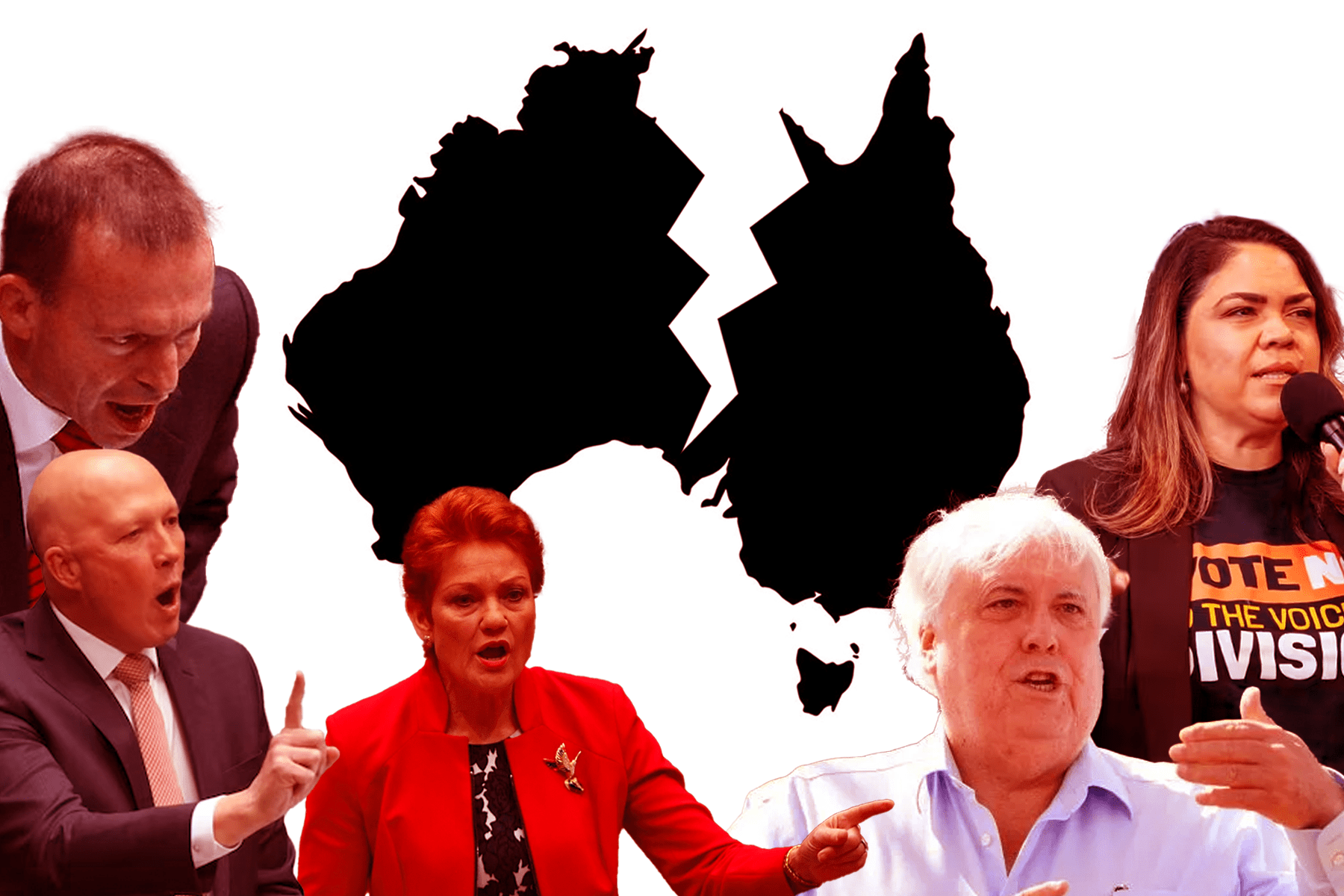

To the extent that disagreement was likely, No campaigners cannot claim that this harm is one caused by the Voice itself, or Albanese. Rather, any increased polarisation or culture war emerging from the Voice is at least equally attributable to the existence (which was not inevitable) of a hostile No campaign, which has relied on dishonesty and disinformation. The No campaign is, by and large, a product of Peter Dutton’s political strategy to oppose the government no matter what. It is hypocritical for Dutton’s No campaign to pin the harm of polarisation to Albanese and the Uluru Statement from the Heart.

These arguments need not even be true. The biggest problem with the claim that the Voice is antithetical to national unity is the fact that disagreement is inherent to democracy, and indeed all systems of government. Disagreement is inherent to a proposal that, on the referendum ballot, requires a “Yes” or “No” answer. This is not necessarily a bad thing. It is lazy to claim that the Voice is “divisive” because people will support it and oppose it. That is true of almost every proposal. That is, essentially, to argue that people should oppose the Voice because some people, already or soon will, oppose the Voice. Indeed, it is counterproductive to make this argument; to encourage people to shy away from debate is to weaken democracy, and in the process to disengage people when it is in everyone’s best interests to be politically engaged.

The claim it is “racially divisive” for First Nations people to be recognised in the Constitution is perhaps less nonsensical, but should be rejected regardless.

The Constitution is not, as No supporters claim, “race-blind”. Section 51 (xxvi) of the Constitution, the so-called “race power”, has always allowed the parliament to make “laws … with respect to people of any race”. Although the provision originally excluded First Nations people from the ambit of this power, at the 1967 referendum 97% of voters voted to explicitly give the parliament power to make laws with respect to First Nations people. It surely makes sense for First Nations people to be allowed to provide input into these laws.

Claims which frame the Voice in terms of “race” are misfounded. The Voice is not a matter of race, but of recognising the rights of First Nations people, who have been custodians of the land now called “Australia” for 65,000 years. Indigenous peoples worldwide, inherently, morally, and under international law, have a right to self-determination. The Voice is a very small step towards the fulfilment of this right — which extends to the ability to make binding decisions, not just to advise upon them — in an Australian context.

But, at its core, the argument that the Voice is “racially divisive” boils down to the claim that First Nations people should be treated equally to everyone else.

It is impossible to ignore Australia’s history when responding to this argument. Australia was founded upon racial division. The settler-colonial project of Australia was premised upon the destruction of First Nations people and their replacement by the colonial system now known as “Australia”. Australia’s history of violence against First Nations people is abhorrent. From the violence of invasion, to the frontier massacres, to the Stolen Generations and beyond, First Nations people have never been treated on the same footing as White Australians.

The violence of the past cannot simply be forgotten, or moved on from. This is a matter of principle: inaction legitimises historic injustice by leaving unchallenged the enduring structures which perpetuated it. It is also a matter of policy: colonisation has had severe and ongoing negative effects for First Nations people. They are the most incarcerated people on earth, die eight years younger than non-indigenous people, and only seven per cent of young First Nations people have a university degree. Undoing the intergenerational disadvantage and trauma of First Nations people necessitates differentiated treatment. The Voice, in listening to First Nations people on the laws which affect them, will give this process the best chance of succeeding.

Besides the fact that poor outcomes are themselves evidence of unequal treatment, First Nations people are still sometimes singled out for differentiated treatment. In launching the Northern Territory Intervention, the Howard government suspended the Racial Discrimination Act. The government is uniquely paternalistic towards First Nations people. It is wrong, and doesn’t work.

In all of this, it is clear that treating First Nations “equally” as non-indigenous people does not lead to equal outcomes. Voting “No”, rather than leading to equal treatment, will entrench the inequalities present in Australian society.

To an extent, most of these arguments are made from the vantage point of White Australia, or at least they appeal to it. Eighty-three per cent of First Nations people support the Voice. The Uluru Statement from the Heart is an expression by First Nations people on how they wish to belong in White Australia. The claim a No vote will maintain unity, by avoiding division, invites the questions: unity for who? On what terms? Any “unity” produced by a No-vote will support a vision of Australia in which the wishes of First Nations people are ignored. It will be a unity made on White Australia’s terms. It will be a false unity.